A Review of Web Based Interventions Focusing on Alcohol Use

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Yatan Pal Singh Balhara

Department of Psychiatry, National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi ? 110 029, India.

E-mail: ypsbalhara@gmail.com

Abstract

Alcohol continues to be a major contributor to morbidity and mortality globally. Despite the scientific advances, alcohol use related problems continue to pose a major challenge to medicine and public health. Internet offers a new mode to provide health care interventions. Web based interventions (WBIs) provide the health care services at the door steps of the end users. WBIs have been developed for alcohol use related problems over the past few years. WBIs offer a potentially relevant and viable mode of service delivery to problem alcohol users. Hence, it is important to assess these interventions for their effectiveness. Some of the existing WBIs for alcohol use assessed systematically in controlled trials. The current review evaluates the available evidence for the effectiveness of WBIs for reducing alcohol use. The literature search was performed using MedLine, PubMed, PsycINFO and EMBASE for relevant English language articles published up to and including April 2013. Only publications focused on reducing alcohol use through WBIs were included.

Keywords

Alcohol, Internet, Interventions, Web based

Introduction

Alcohol continues to be a major contributor to morbidity and mortality globally.[1] Overall, 4% of the global burden of disease is attributable to alcohol.[2] Effective and evidence based management is available for management of alcohol use disorders. A variety of pharmacological and psycho-social interventions are available to treat alcohol dependence. It has been shown that early intervention in primary care is feasible and effective. Despite the scientific advances, alcohol use related problems continue to pose a major challenge to medicine and public health.[2] The situation is worse in Low and Middle Income countries. These countries are faced with the dual challenge of an increase in per capita consumption of alcoholic beverages and limited resources for management of problems associated with alcohol use. A deficit of trained human resources is reflected in lack of services in many parts of these countries, especially the smaller towns, villages and remote areas. Increasing demands of day-to-day life leave even the city dwellers with little time to make regular visits to health care professionals.

Internet offers a new mode to offer health care interventions. Web based interventions (WBIs) provide health care services at the door steps of the end users. These interventions offer the benefits such as ease of access, anonymity and comfort of access at a desired time. In addition, these interventions help overcome the barriers of distance and can potentially be offered to a large number of end users. These services are also efficient and economical in that they can reach a large number of individuals.[3]

WBIs have been developed for individuals with alcohol use related problems over the past few years. Internet users are on a rise globally. Moreover, it has been seen that problem alcohol users have access to the internet.[4] WBIs offer a potentially relevant and viable mode of service delivery to problem alcohol users. Hence, it is important to assess these interventions for their effectiveness. Some of the existing WBIs for alcohol use assessed systematically in controlled trials. The current review evaluates the available evidence for the effectiveness of WBIs for reducing alcohol use.

Methods of Literature Search

Literature search

The literature search was performed using MedLine, PubMed, PsycINFO and EMBASE for relevant English language articles published up to and including April 2013. Key search terms used in the search were: ([“Online Systems” OR “Internet” OR “Web” OR “Computer”] AND [“Alcohol”] AND [“Intervention” OR “Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)”]). Reference lists of previously published reviews, meta-analyses and the included studies within this topic were also checked. Only publications focused on reducing alcohol use through WBIs were included.

Selection of studies

The effectiveness of an intervention summates multitude of issues. These include rigorousness of research design, level of control over confounding factors, quality of program implementation and intervention fi delity.[5] Therefore, we included studies utilizing solely WBIs that were fully automated and excluded those that required additional elements, such as having face-to-face components or being delivered through intranet or mobile phone.

Abstracts of all potentially relevant articles were reviewed for possible inclusion. We included articles reporting RCT of an internet based alcohol-related intervention with at least one no-treatment control focused on curtailing alcohol use. Trials using internet only for recruitment or to remind participants of appointments for treatment but not for delivering the intervention were excluded. Articles describing study protocols and dissertations were also excluded from the analysis.

Data extraction and analysis

Both authors independently carried out data extraction. Where data was insufficient or not available in the published paper or after contacting corresponding authors, studies were excluded from the analysis.

Results

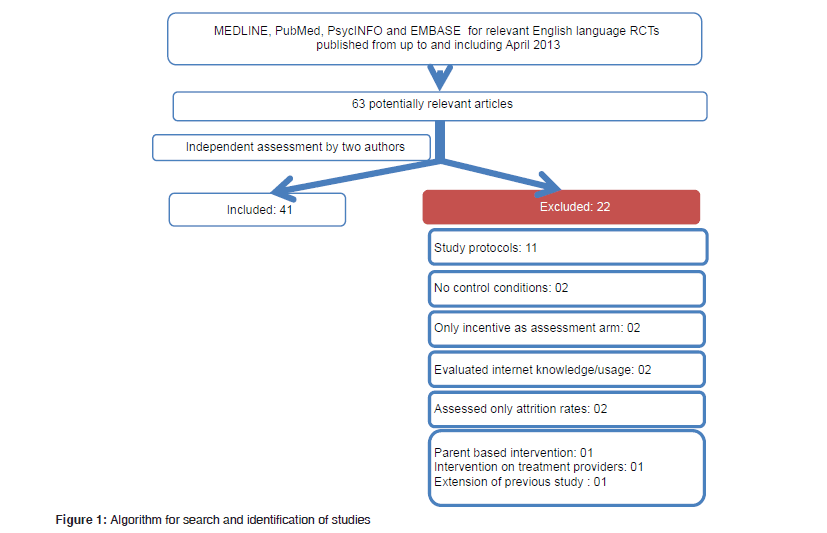

We identified 63 potentially relevant articles evaluating WBI with/without co-interventions for reducing alcohol use [Figure 1]. Out of these 41 articles comprising 35 studies were included after fulfilling the eligibility criteria’s.[6-46] Among the excluded articles, eleven were study protocols, two had no control condition,[47,48] two studies (one article) had,[49] two studies evaluated only internet knowledge and usage,[50,51] two studies assessed only attrition rates,[52,53] one study focused on parent based intervention,[54] one study focused intervention on treatment providers[55] and one article was only an extension of previous study with an online survey only.[56]

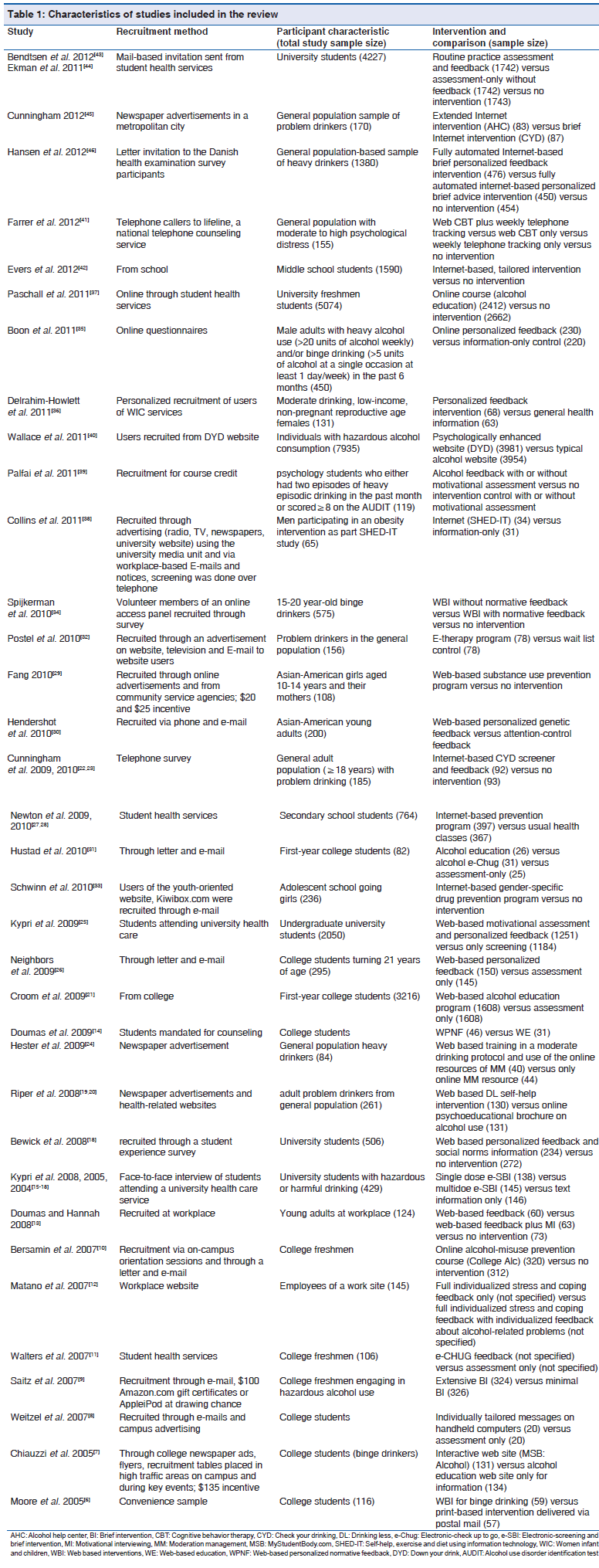

The characteristics of the included studies and participants, results of quality assessment and key findings are described below [Table 1].

Characteristics of Included Studies

Country of origin

Twenty studies were from USA.[6-14,21,24,26,30,31,33,36,37,39,42] Eight studies were from Australia,[15-17,25,27,28,38,41] five from Netherlands,[19,20,32,34,35] three from Canada,[22,23,29,45] two each from Sweden [43,44] and UK [18,40] and one study was from Denmark.[46]

Study subjects

Overall the studies reported data from more than 50,000 participants with sample sizes ranging from a minimum of 65 [38] to a maximum of 5074.[37] Two studies, however, did not specify the number of participants.[11,12]

Fourteen studies recruited adults [12,13,19,20,22-24,30,32,35,36,38,40,41,45,46] and 21 studies recruited school going or college students or adolescents.[6-11,14-18,21,25-29,31,33,34,37,39,42-44] Three studies evaluated only female population.[29,33,36]

Recruitment of study subjects

The subjects were recruited mainly from web with the participants using a particular website finding the WBI through online invitations.[33-35,40] Other recruitment strategies included recruitment through non-internet based advertising (such as television commercials, radio and newspaper announcements, or flyers displayed in the schools at each respective site),[7,24,45] a combination of internet based advertising and referrals from community service agencies,[29] a combination of web based and non-web based advertisements[32,38] and from attendees of Women Infant and Children services.[36] Two studies recruited subjects from workplace.[12,13]

Some studies recruited participants exclusively via single modality such as letter [46], E-mail[9] or telephonically.[22,23,41] Others utilized E-mail in combination with letters[10,26,31] or telephone.[30] Student health services were utilized for recruitment through face-to-face enrolment,[15-17,27,28] via E-mail,[43,44] or online.[37]

Use of incentives

Only three studies reported use of incentives to facilitate participation.[7,9,29] One study offered course credits to the students.[39]

Participant Characteristics

The characteristics of participants also varied across the studies. Majority of the studies involved adolescent or student populations.

WBI studies involving adults included problem drinkers,[20,23,32,45] heavy or binge drinkers,[24,35,46] moderate drinkers [36] and those with hazardous alcohol consumption.[40] Different definitions of drinking were used. Some adult studies involved WBI for alcohol as an auxiliary intervention to another primary focal issue like psychological distress or obesity.[38,41]

Majority of studies among students did not categorically identify alcohol used pattern. In fact, majority of the studies use being 1st year or freshmen as an inclusion criteria. Other studies included participants with binge drinking [7,34] or hazardous or harmful drinking.[15]

Three studies evaluated only female population, one including only adults and the other two female school going students.[29,33,36] Two studies among adults recruited male subjects exclusively.[35,38]

Nature of Interventions

The intensity and rigorousness of WBIs studied across these studies varied from low intensity interventions such as generalized online psycho-educational brochure[20] to extensively tailored cumulative variants of an internet based intervention.[40]

Majority used only web based personalized assessment and feedback as intervention.[11,13,14,25,26,30,35,36,39,43,46] Few used structured modules as cognitive behavior therapy [41] or brief intervention.[9] Few studies among college students utilized an online course.[10,39]

Majority of control groups received only an assessment, whereas others utilized a psycho-educational resource or face-to-face approach. In some interventions, screening or follow-up was done over telephone.[38,41]

While majority of the interventions used a fixed intervention module, some used an individually tailored approach.[8,29,32,42]

Some studies intervened at multiple times and made comparisons with a single time approach.[15-17] While some compared an extended intervention to a brief one.[45] Others compared advise to feedback.[46] Only one study compared WBI to a print based intervention.[6]

None of the studies used any pharmacological agent along with the WBI.

Outcomes Studied

Varied outcome measures have been employed across the studies. Studies utilized some quantitative measure of alcohol consumption such as frequency of drinking, blood alcohol concentration, or amount of alcohol consumed in terms of standard drinks or unit grams of alcohol. Only a few compared binge pattern drinkers with non-binge drinking population or non-drinkers to problem drinkers. A designated assessment period was included which varied among the studies from a typical week, the previous week, 2 or 6 weeks, or up to last 12 months. Few studies assessed either a typical drinking occasion or binge drinking which may be event specific (like use on 21st birthday or pub nights) [7,26] or event non-specific.[37] Many studies also assessed secondary parameters such as problems or consequences related to alcohol use,[8,17,28,31] help seeking intention,[9] self-efficacy,[8] alcohol-related knowledge,[28] or readiness to change.[7,9,24]

Studies comparing WBI to non-WBIs or no interventions at all

Around 71% (10/14) studies involving adult subjects compared a WBI with a non-WBI or no intervention [12,13,22,23,30,32,35,36,38,41,46] as opposed to around 86% (19/22) studies involving children and adolescents.[6,8,10,11,15,18,21,25-29,31,33,34,37,39,42,43]

WBI was found to be more effective in reducing alcohol consumption as compared to non-WBI or no intervention control population in only three studies involving adults.[13,30,32] All these studies were with short-term follow-up. No difference was observed between the different study interventions in four studies.[36,38,41,46] Two studies reported initially significant difference in favor of WBIs which was not sustained on long-term follow-up.[22,23,35] One of the studies was underpowered to comment on the significance of difference.[12]

Of studies involving school or college going children and adolescents, reduced alcohol consumption was observed on many assessment parameters (but not all) in majority of the studies. The significant difference was observed at follow-up interval of 1 month,[25,31,34,39] 3 months[10,18,34] and 12 months.[15,28,29] No intervention benefit was observed in three studies.[6,21,43] In four studies the initial benefit observed with WBIs when compared to controls at immediate post-intervention or 2-3 month post-intervention assessment was lost at later follow-up.[8,11,37,42]

Studies comparing different WBIs

Around 43% (6/14) studies involving adult subjects compared one WBI to another,[13,19,20,24,40,45,46] while only 31.8% (7/22) studies involving children and adolescents reported such comparison.[7,9,14,15,31,34,39]

Among the adult studies, only one study with short-term follow-up (3 month) found a significant difference among different WBIs.[24] Similarly only of the long-term studies found any significant difference among the interventions.[19] Even in this study, the difference at 6 months was lost on long-term follow-up at 12 months.[20] Only one study among college students reported a difference in WBIs with a web-based personalized normative feedback (WPNF) being better than a web-based education (WE) approach. [14] However, this study was with a short-term follow-up of only 1 month.

Conclusions

A steady increase in WBIs for alcohol use makes it necessary to study these interventions systematically. With an increase in penetration of internet these interventions are likely to be offered to a larger number of problem alcohol users. The current article has reviewed the available evidence for these WBIs for alcohol use.

Systematic analysis of WBIs for alcohol use is a rather recent phenomenon. The first RCT involving a WBI for alcohol use was carried out in the year 2005. A total of 41 studies were included in the current review. Majority of the studies are from USA followed by Australia. There are no studies from Asia and Africa. A growing proportion of individuals in Asian and African countries have access to internet these days. Furthermore limited resources and cost-effectiveness of WBIs for alcohol couples with the growing burden of alcohol use problems in these countries makes a case for development and assessment of such WBIs for these countries as well.

The studies have been conducted among children, adolescents and adults. Some studies have focused exclusively on women. Overall a large number of subjects have been recruited in these studies. However, there is a significant inter-study difference for the sample size. Various approached have been utilized to recruit study subjects. These include internet, non-internet based advertising (such as television commercials, radio and newspaper announcements, or flyers displayed in the schools at each respective site), a combination of internet based advertising, referrals from community service agencies, a combination of web based and non-web based advertisements, from attendees of Women Infant and Children services and from the workplace.

There is a lot of heterogeneity across studies with regards to profile of study subjects. These have ranged from problem drinkers to heavy or binge drinkers. Furthermore definitions of drinking used varied across the studies. Also the intensity and rigorousness of WBIs studied varied widely from low intensity interventions such as generalized online psycho-educational brochure to extensively tailored cumulative variants of an internet based intervention. Interestingly none of the studies have included pharmacological treatment either as an adjunct or a comparator. The outcome variables also varied across the studies. Some of the studies utilized some quantitative measure of alcohol consumption. Only a few compared binge pattern drinkers with non-binge drinking population. The assessment period also varied widely from a week to up to 12 months.

Only three of fourteen studies among adults found WBIs to be more effective in reducing alcohol consumption as compared to non-WBI or no intervention. Significantly better response was observed for WBIs (for at least some of the variables) in 10 out of 21 studies including students. While the current review showed that interventions for college and university students are more effective than those for adult alcoholics, this result should be viewed with caution. It must be noted that the majority of the WBIs target college and university students who are still in the early stages of their drinking career. Among those, the heavy/problem drinkers are not necessarily dependent on alcohol. Furthermore, not all such interventions among college/university students have been found to be effective on all parameters assessed. Only 10 (out of 21) studies reported a favorable outcome.

Less than 50% of the studies compared two or more WBIs. Only two studies among adults and one among college students found a significant difference among different WBIs. In the two studies among adults web based self-help intervention (Drink Less) and web based training in a Moderate Drinking protocol with the use of the online resources of Moderation Management were found to be significantly better than online psycho-educational brochure and online Moderation Management resource, respectively. Among the college students, a WPNF was found to be better than a WE approach.

However, it remains to be assessed that which components of the WBIs are most effective. Also the cost-effectiveness analysis for these interventions was not included in any of the studies. Impact of interventions on the use of other psycho active substances was also not assessed. Furthermore whether the improvements observed in problem alcohol use lead to improved functioning or quality of life remains to be assessed.

WBIs focusing on alcohol use related problems can play an important role in addressing these problems. However, these interventions need to be studied systematically and rigorously to have a better understanding in this relatively newer intervention modality.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Balhara YP, Mathur S. Alcohol: A major public health problem-South Asian perspective. Addict Dis Treatment 2012;11:101-20.

- Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet 2005;365:519-30.

- Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: A qualitative review. Addict Behav 2008;33:994-1005.

- Cunningham JA, Blomqvist J. Examining treatment use among alcohol-dependent individuals from a population perspective. Alcohol Alcohol 2006;41:632-5.

- Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, Castro FG, Gottfredson D, Kellam S, et al. Standards of evidence: Criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev Sci 2005;6:151-75.

- Moore MJ, Soderquist J, Werch C. Feasibility and efficacy of a binge drinking prevention intervention for college students delivered via the Internet versus postal mail. J Am Coll Health 2005;54:38-44.

- Chiauzzi E, Green TC, Lord S, Thum C, Goldstein M. My student body: A high-risk drinking prevention web site for college students. J Am Coll Health 2005;53:263-74.

- Weitzel JA, Bernhardt JM, Usdan S, Mays D, Glanz K. Using wireless handheld computers and tailored text messaging to reduce negative consequences of drinking alcohol. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2007;68:534-7.

- Saitz R, Palfai TP, Freedner N, Winter MR, Macdonald A, Lu J, et al. Screening and brief intervention online for college students: The ihealth study. Alcohol Alcohol 2007;42:28-36.

- Bersamin M, Paschall MJ, Fearnow-Kenney M, Wyrick D. Effectiveness of a Web-based alcohol-misuse and harm-prevention course among high- and low-risk students. J Am Coll Health 2007;55:247-54.

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A controlled trial of web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prev Sci 2007;8:83-8.

- Matano RA, Koopman C, Wanat SF, Winzelberg AJ, Whitsell SD, Westrup D, et al. A pilot study of an interactive web site in the workplace for reducing alcohol consumption. J Subst Abuse Treat 2007;32:71-80.

- Doumas DM, Hannah E. Preventing high-risk drinking in youth in the workplace: A web-based normative feedback program. J Subst Abuse Treat 2008;34:263-71.

- Doumas DM, McKinley LL, Book P. Evaluation of two Web-based alcohol interventions for mandated college students. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009;36:65-74.

- Kypri K, Langley JD, Saunders JB, Cashell-Smith ML, Herbison P. Randomized controlled trial of web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:530-6.

- Kypri K, McAnally HM. Randomized controlled trial of a web-based primary care intervention for multiple health risk behaviors. Prev Med 2005;41:761-6.

- Kypri K, Saunders JB, Williams SM, McGee RO, Langley JD, Cashell-Smith ML, et al. Web-based screening and brief intervention for hazardous drinking: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2004;99:1410-7.

- Bewick BM, Trusler K, Mulhern B, Barkham M, Hill AJ. The feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based personalised feedback and social norms alcohol intervention in UK university students: A randomised control trial. Addict Behav 2008;33:1192-8.

- Riper H, Kramer J, Smit F, Conijn B, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Web-based self-help for problem drinkers: A pragmatic randomized trial. Addiction 2008;103:218-27.

- Riper H, Kramer J, Keuken M, Smit F, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Predicting successful treatment outcome of web-based self-help for problem drinkers: Secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e46.

- Croom K, Lewis D, Marchell T, Lesser ML, Reyna VF, Kubicki-Bedford L, et al. Impact of an online alcohol education course on behavior and harm for incoming first-year college students: Short-term evaluation of a randomized trial. J Am Coll Health 2009;57:445-54.

- Cunningham JA, W i l d TC, Cor d i n g l e y J , van Mierlo T, Humphreys K. A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention for alcohol abusers. Addiction 2009;104:2023-32.

- Cunningham JA, Wild TC, Cordingley J, Van Mierlo T, Humphreys K. Twelve-month follow-up results from a randomized controlled trial of a brief personalized feedback intervention for problem drinkers. Alcohol Alcohol 2010;45:258-62.

- Hester RK, Delaney HD, Campbell W, Handmaker N. A web application for moderation training: Initial results of a randomized clinical trial. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009;37:266-76.

- Kypri K, Hallett J, Howat P, McManus A, Maycock B, Bowe S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of proactive web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention for university students. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1508-14.

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Walter T. Internet-based personalized feedback to reduce 21st-birthday drinking: A randomized controlled trial of an event-specific prevention intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009;77:51-63.

- Newton NC, Andrews G, Teesson M, Vogl LE. Delivering prevention for alcohol and cannabis using the Internet: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med 2009;48:579-84.

- Newton NC, Teesson M, Vogl LE, Andrews G. Internet-based prevention for alcohol and cannabis use: Final results of the Climate Schools course. Addiction 2010;105:749-59.

- Fang L, Schinke SP, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among early Asian-American adolescent girls: Initial evaluation of a web-based, mother-daughter program. J Adolesc Health 2010;47:529-32.

- Hendershot CS, Otto JM, Collins SE, Liang T, Wall TL. Evaluation of a brief web-based genetic feedback intervention for reducing alcohol-related health risks associated with ALDH2. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:77-88.

- Hustad JT, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. Addict Behav 2010;35:183-9.

- Postel MG, de Haan HA, ter Huurne ED, Becker ES, de Jong CA. Effectiveness of a web-based intervention for problem drinkers and reasons for dropout: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e68.

- Schwinn TM, Schinke SP, Di Noia J. Preventing drug abuse among adolescent girls: Outcome data from an internet-based intervention. Prev Sci 2010;11:24-32.

- Spijkerman R, Roek MA, Vermulst A, Lemmers L, Huiberts A, Engels RC. Effectiveness of a web-based brief alcohol intervention and added value of normative feedback in reducing underage drinking: A randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e65.

- Boon B, Risselada A, Huiberts A, Riper H, Smit F. Curbing alcohol use in male adults through computer generated personalized advice: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e43.

- Delrahim-Howlett K, Chambers CD, Clapp JD, Xu R, Duke K, Moyer RJ 3rd, et al. Web-based assessment and brief intervention for alcohol use in women of childbearing potential: A report of the primary findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2011;35:1331-8.

- Paschall MJ, Antin T, Ringwalt CL, Saltz RF. Evaluation of an Internet-based alcohol misuse prevention course for college freshmen: Findings of a randomized multi-campus trial. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:300-8.

- Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Warren JM, Lubans DR, Callister R. Men participating in a weight-loss intervention are able to implement key dietary messages, but not those relating to vegetables or alcohol: The Self-Help, Exercise and Diet using Internet Technology (SHED-IT) study. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:168-75.

- Palfai TP, Zisserson R, Saitz R. Using personalized feedback to reduce alcohol use among hazardous drinking college students: The moderating effect of alcohol-related negative consequences. Addict Behav 2011;36:539-42.

- Wallace P, Murray E, McCambridge J, Khadjesari Z, White IR, Thompson SG, et al. On-line randomized controlled trial of an internet based psychologically enhanced intervention for people with hazardous alcohol consumption. PLoS One 2011;6:e14740.

- Farrer L, Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Mackinnon A. Web-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression with and without telephone tracking in a national helpline: Secondary outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e68.

- Evers KE, Paiva AL, Johnson JL, Cummins CO, Prochaska JO, Prochaska JM, et al. Results of a transtheoretical model-based alcohol, tobacco and other drug intervention in middle schools. Addict Behav 2012;37:1009-18.

- Bendtsen P, McCambridge J, Bendtsen M, Karlsson N, Nilsen P. Effectiveness of a proactive mail-based alcohol Internet intervention for university students: Dismantling the assessment and feedback components in a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e142.

- Ekman DS, Andersson A, Nilsen P, Ståhlbrandt H, Johansson AL, Bendtsen P. Electronic screening and brief intervention for risky drinking in Swedish university students – A randomized controlled trial. Addict Behav 2011;36:654-9.

- Cunningham JA. Comparison of two internet-based interventions for problem drinkers: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e107.

- Hansen AB, Becker U, Nielsen AS, Grønbæk M, Tolstrup JS, Thygesen LC. Internet-based brief personalized feedback intervention in a non-treatment-seeking population of adult heavy drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e98.

- Blow FC, Barry KL, Walton MA, Maio RF, Chermack ST, Bingham CR, et al. The efficacy of two brief intervention strategies among injured, at-risk drinkers in the emergency department: Impact of tailored messaging and brief advice. J Stud Alcohol 2006;67:568-78.

- Wallace P, Linke S, Murray E, McCambridge J, Thompson S. A randomized controlled trial of an interactive Web-based intervention for reducing alcohol consumption. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12 Suppl 1:52-4.

- Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Kalaitzaki E, White IR, McCambridge J, Thompson SG, et al. Impact and costs of incentives to reduce attrition in online trials: Two randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e26.

- Truncali A, Lee JD, Ark TK, Gillespie C, Triola M, Hanley K, et al. Teaching physicians to address unhealthy alcohol use: A randomized controlled trial assessing the effect of a Web-based module on medical student performance. J Subst Abuse Treat 2011;40:203-13.

- Cunningham JA, Kypri K, McCambridge J. The use of emerging technologies in alcohol treatment. Alcohol Res Health 2011;33:320-6.

- McCambridge J, Kalaitzaki E, White IR, Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Linke S, et al. Impact of length or relevance of questionnaires on attrition in online trials: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e96.

- Postel MG, de Haan HA, ter Huurne ED, van der Palen J, Becker ES, de Jong CA. Attrition in web-based treatment for problem drinkers. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e117.

- Donovan E, Wood M, Frayjo K, Black RA, Surette DA. A randomized, controlled trial to test the efficacy of an online, parent-based intervention for reducing the risks associated with college-student alcohol use. Addict Behav 2012;37:25-35.

- Crits-Christoph P, Ring-Kurtz S, McClure B, Temes C, Kulaga A, Gallop R, et al. A randomized controlled study of a web-based performance improvement system for substance abuse treatment providers. J Subst Abuse Treat 2010;38:251-62.

- Riper H, Kramer J, Conijn B, Smit F, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Translating effective web-based self-help for problem drinking into the real world. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:1401-8.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.