Civic Recovery Mentorship: An Online Undergraduate Medical Training Program to Transform Experience into Expertise, and Attitudes into Competencies

2 Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, USA, Email: jean-francois.pelletier@yale.edu

Citation: Jean-Francois Pelletier. Civic Recovery Mentorship: An Online Undergraduate Medical Training Program to Transform Experience into Expertise, and Attitudes into Competencies. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2017; 7: 73-75

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

While recovery is the current leading paradigm in the transformation of mental health systems throughout the world, recovery principles and values are slowly and quietly also embracing physical health for continuity and holistic health. A key feature of recovery-oriented systems is to have patients or former patients involved as active partners, for instance in the provision of care for them to act as recovery mentors. Informal peer-to-peer relationships are certainly not new. What is still relatively new is that there now exist a variety of formal programs to train recovery mentors, for them to perform this role either in complex multidisciplinary medical teams or in community organizations. This paper describes a first online and for credit program of medical training of recovery mentors. To complete their training the recovery mentor apprentices will need to show, in real clinical or community contexts, that they do master nine key attitudes. In alphabetical order, these attitudes are: altruism, empathy, engagement, honesty and integrity, humility, open-mindedness, respect, rigor, and sense of responsibility. We suggest that the pedagogical approach to teach how to express these attitudes need to be based more on principles of adult education (andragogy) than on those of youth education (pedagogy) in order to facilitate the emulation of recovery.

Keywords

Supported medical education; Techno-andragogy; Therapeutic education; Holistic medicine

Introduction

Recovery is the current leading paradigm in the transformation of mental health systems throughout the world. A key feature of recovery-oriented systems is to have patients or former patients involved as active partners, for instance in the provision of care, [1] in research and evaluation of services, [2] or in continuous medical training. [3] Indeed, persons with the lived experience of mental illness can relate particularly well with newly diagnosed patients by acting as role-models through positive self-disclosure. [4] Recovery mentorship is thus a supportive (not curing) relationship because the recovery mentor provides emotional and social support to others who share a common experience in order to facilitate the emulation of recovery and while constantly instilling hope. The commonality is to the struggle and emotional pain that can accompany the feeling of loss and/or hopelessness due to a mental illness, rather than in relation to a specific symptom or illness. [5]

Informal peer-to-peer relationships are certainly not new. What is relatively new is that there now exist a variety of formal programs to train recovery mentors, for them to perform this role either in complex multidisciplinary medical teams or in community organizations. This paper describes a first online and for credit program of medical training of recovery mentors at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Montreal, Canada.

Structure of the Program and the “Flipped Class” Technique

The curriculum of this ongoing program is comprised of 4 courses, totaling 10 credits, which are spread over a full year rather than grouped together in a single semester. Upon successful completion, students receive a Recovery Mentor License at the same graduation ceremony as that of other graduating medical students. The training begins in the fall semester with the Recovery and Global Health course, in which recovery is presented as a capacity-based, not deficit-based, approach to rehabilitation. Recovery goes beyond the reduction of symptoms and considers an individual’s wellness from a holistic point of view that includes their relationships, their involvement within the community, their general well-being, and their sense of empowerment. [5]

While doctors can treat an illness or symptom, only the patient can engage him- or herself in recovery, mobilizing and building on their own capacity for resilience and willingness to pursue their own quest for well-being and happiness. Recovery mentorship consists in personifying and stimulating this potentiality for personalization, in the sense that recovery is first and foremost a unique person-driven journey.

The course is open to any interested medical or health sciences student (e.g. optional or out-of-program course). Postsecondary undergraduate students in general have significantly higher levels of psychological distress than their peers in the rest of the population. [6] They may face multiple stressors such as pressure to succeed, competition with other students and so on. [7] A study among undergraduate students in Canada showed that 30% of students had psychological distresses, which were significantly higher than in the general population of Canada. [8] Yet, this program is firstly dedicated to persons (and their families) with the lived experience who want to go to, or to go back to university to learn how to transform this experience, which significantly impacted their life trajectory, into expertise to accompany others. These new students are likely to be older than typical students who go straight to college and who need no special accommodation to succeed. Therefore, the pedagogical approach in use is based more on principles of adult education (andragogy) than on those of youth education (pedagogy).

In this “flipped classroom” model, the learner is assigned content to review prior to the teaching session. Class time is used for the application of knowledge in an active learning session. [9] Students can take part in this 90-minute class remotely, but at the same time synchronously for everyone. They are expected to review the 90-minute pre-recorded theoretical material and lectures when they want to (asynchronously), on the condition that it is before the class.

Discussion on Internship

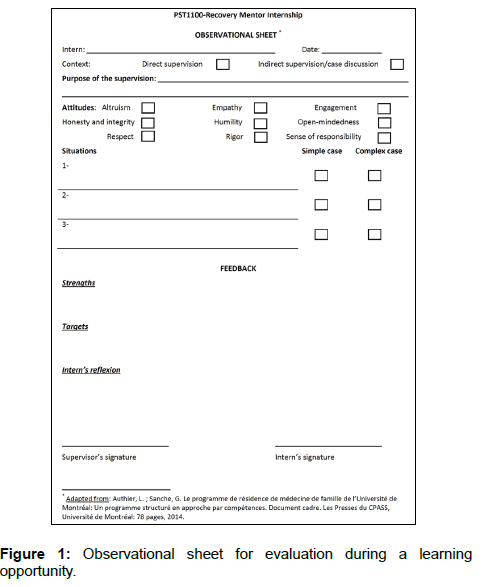

After two other courses (one on the health system and the other on the ethics of recovery), to complete their training the recovery mentor apprentices will need to show, in real clinical or community contexts, that they do master nine key attitudes as recovery mentors, for which they will have been trained (Ethics of Recovery course). In alphabetical order, the attitudes are: Altruism, empathy, engagement, honesty and integrity, humility, open-mindedness, respect, rigor, and sense of responsibility. The expectation is that upon completion of the program, recovery mentor apprentices will be able to behave in such a manner that other experienced recovery mentors would recognize the attitude(s) they are showing off. This evaluation system is inspired by the Canadian Medical Educational Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS). The attitudes are common and transversal to the six competencies of the CanMEDS Framework, which supports the medical expert. The Canadian Medical Educational Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS), which are now used by several medical boards around the world to create competency-based postgraduate training programs, is an educational framework that describes the abilities required by physicians to effectively meet the health care needs of the people they serve (communication, collaboration, health advocacy, leadership, professionalism, and scholarship). [10] When medical graduates start their residency, they should possess certain competencies to be refined during postgraduate training. CanMEDS-like frameworks depicting professional roles and specific professional activities thus provide guidelines for postgraduate medical education. [11] More precisely, attitudes here become competencies that can be observed through manifestations and indicators of attitudes to be put into practice.

Through the expression of their supportive non-judgmental attitudes when involved in medical teams, the recovery mentors will facilitate mutual understanding between professionals and patients: understanding by the patients of the medical information, procedures, and community resources on one hand, and on the other hand, understanding by the team of the patients’ gender-specific recovery narrative and conditions of life. [12,13] Conditions of life, or the contextual factors as defined by the World Health Organization, are gathered in Chap. 21 of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10th version). [14] They are circumstances or problems which influence the person’s health status but are not in themselves current illnesses or injuries. Such factors may be elicited during population surveys, when the person may or may not be currently ill, or be recorded as an additional factor to be borne in mind when the person is receiving care for some illness or injury.

Manifestations of attitudes will be rated in action. They will become competencies over time. These manifestations will be monitored with an observational sheet that enables observation and feedback in real situations to measure learning progress [Figure 1] The internship will consist of providing learning opportunities in common situations involving the mobilization of attitudes. Direct observation will allow structured learning by providing feedback based on explicit criteria, and will stimulate reflexivity on the part of the learner.

Conclusion

E-learning techniques will be used in combination with a flipped class approach to train recovery mentors in a faculty of medicine. On-line support will also be provided to recovery mentor apprentices during their internship and for ongoing associational life and continuous education after graduation. However, the challenge remains to conceptualize and implement a specific techno-andragogy model of supported education that goes beyond simple on-line access to digitize but traditionally produced academic materials and lectures. In the era of social networks, the social aspect should not only be a label but should be genuinely supportive of a sense of community belonging, and not of isolation, even if we go on these social networks solo, for example to find recovery mentorship and peer support.

Conflict of Interest

All authors disclose that there was no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Davidson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, Miller R. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: A review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry. 2012; 11:123-128.

- Pelletier JF, Lesage A, Boisvert C, Bonin JP, Denis F, Kisely S. Feasibility and acceptability of patient partnership to improve access to primary care for the physical health of patients with severe mental illnesses: an interactive guide. BMC Int J Equity Health, 2015; 14:78.

- Pelletier JF, Lesage A, Bonin JP, Bordeleau J, Rochon N, Baril S, et al. When patients train doctors: Feasibility and acceptability of patient partnership to improve primary care providers' awareness of communication barriers in family medicine for persons with serious mental illness. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 2016; 12:112-118.

- Fuhr DC, Salisbury TT, De Silva MJ. Effectiveness of peer-delivered interventions for severe mental illness and depression on clinical and psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014; 49:1691-1702.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Changing directions, changing lives. The mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2012.

- Leahy CM, Peterson RF, Wilson IG. Distress levels and self-reported treatment rates for medicine, law, psychology and mechanical engineering students: cross-sectional study. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2010; 44:608-615.

- Vaez M, Ponce De Leon A, Laflamme M. Health related determinants of perceived quality of life: A comparison between first year university students and their working peers. Work. 2006; 26:167-177.

- Adlaf EM, Gliksman L, Demers A. The prevalence of elevated psychological distress among Canadian undergraduates. J Am Coll Health. 2007; 50: 67-72.

- Morgan H, McLean K, Chapman C, Fitzgerald J, Yousuf A, Hammoud M. The flipped classroom for medical students. Clin Teach. 2015; 12: 155-160.

- Scheele F, Teunissen P, Van Luijk S, Heineman E, Mulder FH, Meininger A, et al. Introducing competency-based postgraduate medical education in the Netherlands. Med Teach. 2008; 30: 248-253.

- Fürstenberg S, Schick K, Deppermann J, Prediger S, Berberat P, Kadmon M, et al. Competencies for first year residents – physicians’ views from medical schools with different undergraduate curricula. BMC Med Educ. 2017; 17:154.

- Pelletier JF. Gender differences to the contextual factors questionnaire and implications for general practice. J Gen Pract, 2017; 5:297.

- Pelletier JF. Significant differences in the civic recovery composite index as a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM): Implications for research and primary care. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2017; 7: 1-8.

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th Revision). Geneva. 1999.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.