Clinico‑Electroencephalography Pattern and Determinant of 2‑year Seizure Control in Patients with Complex Partial Seizure Disorder in Kano, Northwestern Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Owolabi Lukman Femi

Department of Medicine, Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Bayero University, PMB 3452, Kano, Nigeria.

E-mail: drlukmanowolabi@yahoo. com

Abstract

Background: Complex partial seizures (CPS) may present with milder symptoms mimicking normal function of an adult person making the diagnosis delayed or often missed. There is a need for an in‑depth training in epileptology to understand the various pattern of electroclinical presentation of CPS. Ability to predict seizure control on first diagnosis can be very useful in the management of patients with CPS. However, there is a paucity of data on CPS in North‑western Nigeria. Aim: This study aimed to describe the clinical and EEG characteristics of CPS and evaluate independent determinant of 2‑year seizure control among adults with partial epilepsy in Kano, North‑western Nigeria. Subjects and Methods: Out of all patients diagnosed with epilepsy (PWE) at the adult neurology clinic of two tertiary hospitals in Kano over a period of 4½ years, those with CPS were prospectively studied. Diagnosis of CPS was based on both clinical and EEG findings. Patients were followed‑up for a minimum period of 2‑year to determine their seizure control status. Data were analyzed using STATA version 10. Results: Total of 158 (105 males, 53 females) were enrolled. Their age ranged between 15 and 85 (median = 30.5) years. Sixty six (66/158,41.7%) had aura and 64 of them (64/158, 41.1%) had automatism. The most common aura and automatism were abnormal epigastric sensation and oro‑alimentary respectively. Twenty eight (28/158, 18%) had associated behavioral manifestations. EEG abnormality was recorded in 56 (56/158, 53.9%). Adequate seizure control was achieved in 55% (70/128) on anti‑epileptic drugs (AEDs). Duration of epilepsy, before the commencement of AEDs was identified as an independent determinant of 2‑year seizure control. Conclusion: Abnormal epigastric sensation and oroalimentary automatism were the most common clinical complaint. Duration epilepsy over 3 years or less was identified as an independent predictor of 2‑year seizure control. Keywords: Complex

Keywords

Complex partial, Predictor, Seizure, Seizure control

Introduction

At a conservative estimate, over 1% of the world’s population or about 50 million people world-wide suffer from epilepsy. Over four-fifths of these people are thought to be in the developing countries.[1] In Nigeria, the prevalence of epilepsy in defined communities varies from 5/1,000 to 37/1,000.[2,3] One of the early publications on the prevalence of epilepsy in Nigeria reported prevalence of between 8/1,000 and 13/1,000 inhabitants in the urban community of Lagos but with a computed rate of 3.1/1,000.[4] Osuntokun et al., reported a prevalence rate of 5.3/1,000 among inhabitants of Igbo-Ora.[2].

The most common type of adult epilepsy is complex partial seizure (CPS). In the United States of America, CPS occurs in 35% of persons with epilepsy.[5,6] In some studies conducted in Nigeria, CPS appeared to be the most common.[2,3,7] A study conducted in Kano, North-western Nigeria, also reported CPS as the most common type of seizure among adult patients with epilepsy.[8] In spite of this, diagnosis of CPS is often missed by the general practitioners and non-neurologists because of its subtle or peculiar symptoms.

Prediction of seizure control with appropriate treatment can be useful particularly to convince patient and to achieve good patient compliance and it also enables an approximate cost-benefit analysis to be performed thereby allowing care givers to deploy their resources more effectively. Such predictors also assist the development of referral plans and management protocol in resource-poor countries.[9]

The current study, therefore, aimed at profiling the clinical and electroencephalography (EEG) characteristics of CPS as well as evaluate independent 2-year seizure control among a cohort of CPS patients in Kano, North-western Nigeria.

Subjects and Methods

The study was based on prospective systematic study of consecutive CPS disorder patients seen at the adult Neurology Clinic of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital and Murtala Specialist Hospital Kano over a period of 4½ years (January 2008-June 2012).

Ethical approval was obtained for the study and informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

The subjects, who must have had two or more episodes of CPS unrelated to an acute underlying defined cause and who must have been accompanied by an eyewitness such as a parent, spouse, or a close relative living with the patient, were enrolled consecutively. The historical details of the seizure patterns were obtained through interviews with each case and an accompanying relative, followed by physical and neurologic examination. Diagnosis and classification of CPS was in accordance with International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification of epileptic seizures.[10]

EEG recordings were available in most cases, but were not a prerequisite for diagnosis, where patients had EEG, the recordings were obtained during the interictal period using 32-channel grass model EEG equipment. Electrode placement was by the 10-20 cap system. Features such as background alpha-rhythm, voltage symmetry, spikes, sharp waves, slow waves and other paroxysmal discharges were observed. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire, which was pretested for clarity and administered by a neurologist and resident doctors. The questionnaire assessed demographic data such as age, age at onset, occupation and educational status, seizure type, presence and types of aura and automatism, frequency of seizure, anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) etc., Age at onset was defined as the first age at which seizures were observed.

All patients had AEDs (carbamazepine in most cases). Mono therapy was ensured with the exception of few cases that had combination therapy (carbamazepine and valproate). If patients were already receiving other AEDs without adequate seizure control after optimization of the AEDs, the drugs were gradually withdrawn after second AEDs had been introduced slowly every 1 or 2 weeks. The dose of carbamazepine was based either on response to therapy or on body weight, using 15-20 mg/ kg/body weight as a guide, whilst for sodium valproate the guide dose was 25-30 mg/kg/body weight. All patients were followed-up initially at monthly intervals, then at 2 or 3 months and subsequently at 4 monthly intervals. The patients were followed-up for a minimum period of 2 years. Seizure outcome was categorized as inadequate seizure control if patient had an attack despite appropriate medical therapy with at least two AEDs in maximally tolerated doses for 2 years.[10]

Analyses of data were performed using a statistical software package STATA version 10(Statacorp LP, USA). . Descriptive statistics were depicted using absolute numbers, simple percentages, range and measures of central tendency (mean, median) as appropriate. The Chi square-test was used to test the significance of associations between categorical groups. The variables considered included age at presentation, age at the onset of epilepsy, gender, marital status, level of education, duration of epilepsy (duration from the onset of epilepsy until the commencement of the study), presence of aura, presence of automatism and presence of EEG abnormality. A logistic multiple regression model was used and the covariates were adjusted for each independent (regression) variable to find independent determinant of seizure control. Variables included in the regression model were those that had a significant P value (P < 0.05) in the bivariate analysis with 2-year seizure control as dependent variable. Statistical significance was fixed at probability level of 0.05 or less.

Results

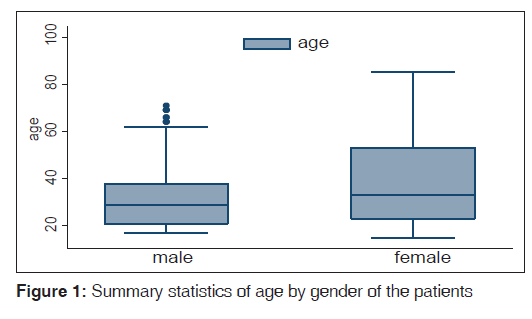

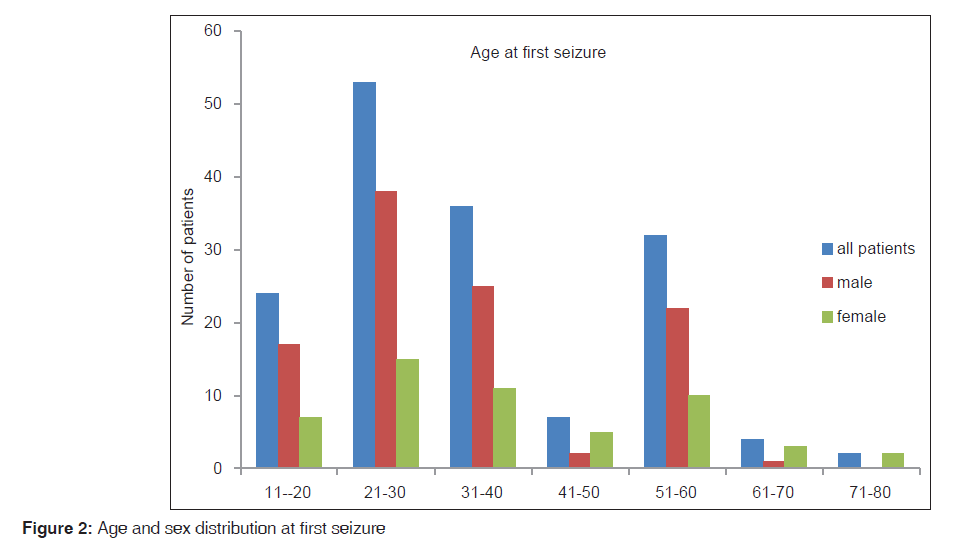

A total of 158 constituting 40.3% (158/392) of all patients diagnosed with epilepsy seen during the study period were enrolled in the study. Thirty (30/158,19%) were lost to follow-up. Patients comprised 105 (105/158, 66.5%) males and 53 (33.5%) females. Their age ranged between 15 and 85 with the median age of 30.5 years. Figure 1 (box plot) showed the statistics of their age at presentation by gender while Figure 2 showed distribution their age at the onset of seizure disorder across gender.

Fifty eight (58/158,36.7%) of patients had the illness for less than 1 year while 100 (100/158,63.3%) have had the illness for more than 1 year. Attack lasted less than 3 min in the majority (127/158,80%) of the patients.

Sixty six (66/158,41.7%) patients had aura and 64 (64/158,60.8%) had automatism. The pattern of aura and automatism are as outlined in Table 1. Family history was present in 14 (14/158,8.9%) patients and 37 (37/158,23.4%) had a positive history of febrile convulsion in childhood. Twenty eight (28/158,18%) had associated behavioral manifestations ranging from transient experiential illusions, hallucination to emotional or affective disturbance.

| Seizure characteristics | Frequency | Percent* |

|---|---|---|

| Aura | ||

| Present | 66 (out of 128 patients) | 41.7 |

| Types | ||

| Sensory | 36 | 54.6 |

| Motor | 22 | 33.3 |

| Psychic | 6 | 9.1 |

| Autonomic | 2 | 3.0 |

| Automatism | ||

| Present | 64 (out of 128 patients) | 41.1 |

| Types | ||

| Oro-alimentary | 49 | 76.6 |

| Ambulatory | 10 | 15.6 |

| Verbal | 5 | 7.8 |

| Responsive | 2 | 3.1 |

| Mimicry | 2 | 3.1 |

*Expressed as percentage of patient with aura or automatism

Table 1: Distribution of seizure characteristics of the patients

One hundred and four (104/158, 65.8%) had first interictal EEG out of which EEG abnormality was recorded in 56 (56/158, 35.4%). EEG abnormality seen included focal epileptic discharges in 48 patients, sudden focal attenuation of background waves in 10 patients and focal slow wave activity in 28 patients occurring singly or in combination.

Sixty seven (67/158,42.4%) had tried traditional or alternative treatment before been seen by a physician. Following evaluation, all the patients had anticonvulsants, 154 (154/158, 97.5%) patients had carbamazepine (control release) and 4 (4/158,2.5%) had valproate, 3 (3/158, 1.9%) had carbamazepine-valproate combination. Fifteen (15/158,9.5%) had phenytoin.

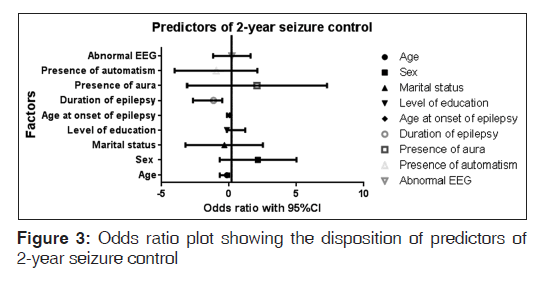

With these medications, 70 (70/128, 55%) out of the 128 patients followed-up had adequate seizure control. No mortality was recorded during the study period. Table 2 and Figure 3 showed the result of multivariate analysis; duration of epilepsy was identified as independent determinant of 2-year seizure control.

| Factors | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| limit | limit | |||

| Age | −0.686 | −0.1561 | 0.0188 | 0.12 |

| Sex | 2.151 | −0.6946 | 4.9968 | 0.14 |

| Marital status | −0.347 | −3.222 | 2.5282 | 0.81 |

| Level of education | −0.147 | −1.5067 | 1.2128 | 0.83 |

| Age at onset of seizure | −0.044 | −0.1481 | 0.0591 | 0.40 |

| Duration of epilepsy | −1.603 | −2.6985 | −0.5077 | <0.01* |

| Presence of aura | 2.090 | −3.1063 | 7.2875 | 0.43 |

| Presence of automatism | −0.955 | −4.0282 | 2.1180 | 0.54 |

| Abnormal EEG | 0.209 | −1.1928 | 1.6100 | 0.77 |

EEG: Electroencephalography. *P value is statistically significant

Table 2: Result of multivariate analysis (logistic regression) for independent determinant of seizure control

Discussion

The study showed male predominance. This finding is similar to reports from studies conducted in Kano,[8] and elsewhere.[11-13] The reason for this is not fully known, but this male preponderance could be partly attributed to the pattern of hospital attendance in the environment where the study was conducted.[14] It may also be ascribed to occupational and social exposure to epileptogenic insults such as head injury that are commoner among male gender.

It appeared the majority of the patients were between 20 years and 40 years age bracket. This finding agreed with reports from similar studies elsewhere.[12,13] Family history of epilepsy was reported in the minority of the patients; however, this could have been underreported considering the social stigma associated with epilepsy and family of people living with epilepsy in our setting.

In the current study, about one in five patients had a history of febrile seizure in childhood. The association between febrile convulsions and temporal lobe epilepsy is well-recognized.[15] Population based studies have shown that the risk of epilepsy, with special reference to CPS, after febrile convulsion varies from 2% to 2.5%. A history of febrile convulsions is present in 10-15% of people with epilepsy or unprovoked seizure, several times higher than the 2-4% seen in the general population.[15,16] Among children with febrile seizure three factors have been well- established as predictors of later epilepsy, namely family history of epilepsy, pre-existing neurologic or developmental abnormalities and complex febrile seizures, with each complex feature of febrile seizures being an independent predictor of later afebrile seizures.[15,17]

Patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy and mesial temporal sclerosis often have histories of severe febrile convulsions as infants. Diagnostic advances made possible by magnetic resonance imaging have shown that very prolonged febrile convulsions may produce hippocampal injury and that focal cortical dysgenesis may play a role in the etiology of febrile convulsions, mesial temporal sclerosis and temporal lobe epilepsy manifesting as CPS.[18] In another study, even after surgery, prolonged febrile convulsion was reported as the most important determinant of CPS of temporal lobe origin with hippocampal sclerosis.[19] Thus, the benefit of adequate prevention as well as timely attention to children with febrile convulsion cannot be overemphasized.

Behavioral manifestations in our study included emotional and affective symptoms as well as hallucination and illusions. CPS of frontal lobe origin are frequently mistaken for psychogenic seizures as they do not necessarily cause complete loss of consciousness and often have very emotional or sexual content.[20-23] There have also been reports where the site of temporal lobe lesions was correlated with certain neuropsychiatric disorders.[20]

Over 40% (42%) of the patients studied had aura and the most common aura was abnormal epigastric sensation. According to ILAE,[9] aura is that portion of the seizure which occurs before consciousness is impaired and for which memory is retained afterwards. Several reports in the literature have emphasized the importance of the aura in the clinical diagnosis of CPSs particularly of temporal lobe origin with the most common being abdominal in origin.[24-26] Similar observations have also been made by other workers.[27]

Gowers,[25] in 1901 reported an incidence of aura of 57%. Lennox and Cobb,[26] found an aura in 764 patients out of 1527 cases (56%). Gupta et al.,[24] reported frequency of aura among patients with CPS as 64%. A slight variation in the Figures in CPS reported by other workers as well as that found in our study may be partly ascribed to the different sample size in the studies. The importance of aura cannot be overemphasized. In fact, aura has also been shown to have localizing value,[28] for instance, unilateral sensory aura, hemi field visual or sensory aura will localize epileptic focus to the contralateral side with sensitivity of 89% and 100% respectively.[29] However, anatomical correlation of aura was not explored in the current study.

Automatisms which are non-purposeful, stereotyped and repetitive behaviors that commonly accompany CPSs were not uncommon (41%) in the current study. The most common form of automatism in the study was oroalimentry automatism. This finding agreed with reports from studies elsewhere.[30,31] Automatism, like aura, has a localizing value; for instance unilateral manual automatisms accompanied by contralateral arm dystonia usually indicates seizure onset from the cerebral hemisphere ipsilateral to the manual automatisms.[31]

First EEG was abnormal in 54% of the patients in the present study. This finding was in conformity with what is already known of the yield of first EEG in epilepsy.[32] Focal epileptiform activity varies greatly in its incidence, both within and between the subjects and is often influenced by state of awareness. In addition to typical spikes, sharp waves and sharp and slow wave complexes, some patients exhibited runs of focal slow activity in the delta or theta range. Nonetheless, because electrical discharges due to CPS may involve only subcortical brain regions, EEG findings may appear non-specific or unremarkable even during active seizures.[33] In addition to the clinical history; the diagnosis of CPS disorder can be aided by EEG. However, since such diagnosis remains a clinical one, it should be noted that several normal EEGs do not rule out the diagnosis of CPSs in a given patient.[34]

In conformity with what is already known about CPS disorder,[35] a little above half of the patients had good 2-year seizure control and a modest proportion of the patients entering seizure-free intervals did so without anticonvulsant dose manipulation. Duration of epilepsy was the only independent predictors or determinant of a 2-year seizure control in our study. This finding was consistent with previous reports.[36,37] Even after epileptic surgery, Janszky et al., reported that epilepsy duration had a significantly higher prognostic value in predicting the 5-year outcome.[19] Nonetheless, uncertainty surrounds the mechanism by which chronicity of epileptic seizures brings about poor outcome. Following initial precipitating injury such as febrile seizures in childhood, the first unprovoked seizure appears long after a silent period.[36,37] After the first unprovoked seizure, it takes some additional years for epilepsy to become pharmacologically resistant.[37] Moreover, longer epilepsy duration has been found to be associated with chronic structural and functional abnormalities; Jokeit et al., reported an association between the epilepsy duration and the bilateral decline of hippocampal volume, brain glucose metabolism and Wada hemispheric memory performance.[38]

Given that CPS, particularly of temporal lobe origin, may involve gross disorders of thought and emotion, patients with CPSs may present diagnostic challenges and frequently go to the attention of psychiatrists. However, since symptoms may occur in the absence of dramatic convulsion, physicians may often fail to recognize the epileptic origin of the disorder resulting in misdiagnosis that is commonly seen in the case of CPS disorder. Fortunately, however, the illness is marked by certain “signature” symptoms that can aid in its identification.[34] Thus, acquaintance of clinicians with common mode of presentation and independent determinant of outcome in cases of CPS disorder will undoubtedly be diagnostically rewarding.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the most common age of onset of CPS was between the second and fourth decade of life; the most common aura and automatism were abnormal epigastric sensation and oroalimentary automatism respectively; the first EEG showed localized abnormalities in over half (54%) of the patients and that duration of epilepsy over 3 years or less was identified as an independent predictor of 2-year seizure control.

Source of Support

Nil.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Secretariat of ILAE/IBE/WHO Global Campaign Against Epilepsy. Epilepsy, a manual for medical and clinical officers in Africa. Geneva, World Health Organization 2002 (WHO/ MSD/MBD/02.02)

- Osuntokun BO, Adeuja AO, Nottidge VA, Bademosi O, Olumide A, Ige O, et al. Prevalence of the epilepsies in Nigerian Africans: A community-based study. Epilepsia 1987;28:272-9.

- Osuntokun BO, Odeku EL. Epilepsy in Ibadan, Nigeria. A study of 522 cases. Afr J Med Sci 1970;1:185-200.

- Dada TO. Epilepsy in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Med Sci 1970;1:161-84.

- Annegers JF. The epidemiology of epilepsy. In Wyllie E, editor. The Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. p. 165-2.

- Consensus statements: Medical management of epilepsy. Neurology 1998;51 5 Suppl 4:S39-43.

- Danesi MA, Oni K. Profile of epilepsy in Lagos, Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med 1983;35:9-13.

- Owolabi LF, Sale S. Profile of epilepsy in developing countries: Experience at Kano, Northwestern Nigeria. Borno Med J 2011;8:33-7.

- Banu SH, Khan NZ, Hossain M, Ferdousi S, Boyd S, Scott RC, et al. Prediction of seizure outcome in childhood epilepsies incountries with limited resources: A prospective study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2012;54:918-24.

- Dreifuss FE, Bancaud J, Henriksen O, Rubio-Donnadieu F, SeinoM. Proposalfor revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. From the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1981;22:489-501.

- Berg AT, Vickrey BG, Testa FM, Levy SR, Shinnar S, DiMario F, et al. How long does it take for epilepsy to become intractable?A prospective investigation. Ann Neurol 2006;60:73-9.

- Abbasher H, Ahmed AE, Salah M, Sidig A. Clinical pattern of partial epilepsy in Sudanese patients. Sudanese J Public Health 2008;3:26-31.

- Berkovic SF, Andermann F, Olivier A, Ethier R, Melanson D, Robitaille Y, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in temporal lobe epilepsy demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 1991;29:175-82.

- Owolabi LF, Akinyemi RO, Owolabi MO, Sani UM, Ogunniyi A. Epilepsy profile in adult Nigerians with late onset epilepsy secondary to brain tumor Neurology Asia 2013; 18: 23-27.

- Singhi PD, Srinivas M. Febrile seizures. Indian Pediatr 2001;38:733-40.

- Hamati-Haddad A, Abou-Khalil B. Epilepsy diagnosis and localization in patients with antecedent childhood febrile convulsions. Neurology 1998;50:917-22.

- Berg AT, Shinnar S. The contributors of epilepsy to the understanding of childhood seizures and epilepsy. J Child Neurol 1994; 9: l9-26.

- Lewis DV. Febrile convulsions and mesial temporal sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol 1999;12:197-201.

- Janszky J, Janszky I, Schulz R, Hoppe M, Behne F, Pannek HW, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis: Predictors for long-term surgical outcome. Brain 2005;128:395-404.

- Jobst BC, Siegel AM, Thadani VM, Roberts DW, Rhodes HC, Williamson PD. Intractable seizures of frontal lobe origin: Clinical characteristics, localizing signs, and results of surgery. Epilepsia 2000;41:1139-52.

- Williamson PD, Spencer DD, Spencer SS, Novelly RA, Mattson RH. Complex partial seizures of frontal lobe origin. Ann Neurol 1985;18:497-504.

- So NK. Mesial frontal epilepsy. Epilepsia 1998;39 Suppl 4:S49-61.

- Gupta AK, Jeavons PM. Complex partial seizures: EEG foci and response to carbamazepine and sodium valproate. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985;48:1010-4.

- Gupta AK, Jeavons PM, Hughes RC, Covanis A. Aura in temporal lobe epilepsy: Clinical and electroencephalographic correlation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1983;46:1079-83.

- Gowers WR. Epilepsy and Other Chronic Convulsive Diseases; their Causes, Symptoms and Treatment. London: Churchill; 1901. p. 320.

- Lennox WG, Cobb S. Epilepsy XIII. Aura in epilepsy: A statistical review of 1359 cases. Arch Neurol 1933;30:374-87.

- Gloor P, Olivier A, Quesney LF, Andermann F, Horowitz S. The role of the limbic system in experiential phenomena of temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol 1982;12:129-44.

- Loddenkemper T, Kotagal P. Lateralizing signs during seizures in focal epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2005;7:1-17.

- Horváth R, Kalmár Z, Fehér N, Fogarasi A, Gyimesi C, Janszky J. Brain lateralization and seizure semiology: Ictal clinical lateralizing signs. Ideggyogy Sz 2008;61:231-7.

- Janszky J, Fogarasi A, Magalova V, Gyimesi C, Kovács N, Schulz R, et al. Unilateral hand automatisms in temporal lobe epilepsy. Seizure 2006;15:393-6.

- Mirzadjanova Z, Peters AS, Rémi J, Bilgin C, Silva Cunha JP, Noachtar S. Significance of lateralization of upper limb automatisms in temporal lobe epilepsy: A quantitative movement analysis. Epilepsia 2010;51:2140-6.

- Marsan CA, Zivin LS. Factors related to the occurrence of typical paroxysmal abnormalities in the EEG records of epileptic patients. Epilepsia 1970;11:361-81.

- Roffman JL, Stern TA. A complex presentation of complex partial seizures. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2006;8:98-100.

- Restak R. Complex partial seizures present diagnostic challenge. Psychiatry Times 1995;12:1-4.

- Devinsky O. Patients with refractory seizures. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1565-70.

- French JA, Williamson PD, Thadani VM, Darcey TM, Mattson RH, Spencer SS, et al. Characteristics of medial temporal lobe epilepsy: I. Results of history and physical examination. Ann Neurol 1993;34:774-80.

- Wieser HG, ILAE Commission on Neurosurgery of Epilepsy. ILAE Commission Report. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. Epilepsia 2004;45:695-714.

- Jokeit H, Ebner A, Arnold S, Schüller M, Antke C, Huang Y, et al. Bilateral reductions of hippocampal volume, glucosemetabolism, and wada hemispheric memory performance are related to the duration of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurol 1999;246:926-33.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.