Comparison between Three Rare Cases of Co‑Infection with Dengue, Leptospira and Hepatitis E: Is Early Endothelial Involvement the Culprit in Mortality?

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Tanmoy Ghatak

Rammohan Pally, Arambagh, Hooghly - 712 601, West Bengal, India.

E-mail: tanmoyghatak@gmail.com

Abstract

Co‑infection in immunocompetent patients is rare. Though co‑infection with dengue and leptospira cases is increasingly reported, a co‑infection of this combination along with hepatitis E is rarely thought of. Until date only two case of triple co‑infection have been reported world‑wide. Here, we are reporting a patient with co‑infection of dengue, leptospirosis and hepatitis E admitted to our intensive care unit. Early septic shock and increasing procalcitonin in dengue patient raised suspicion of co‑infection. Our aim is to educate intensivists about this rare co‑infection and hence that timely initiation of appropriate diagnostic, therapeutic and supportive measures can alter outcome favorably.

Keywords

Co-infection, Dengue, Endothelium, Hepatitis E, Leptospirosis

Introduction

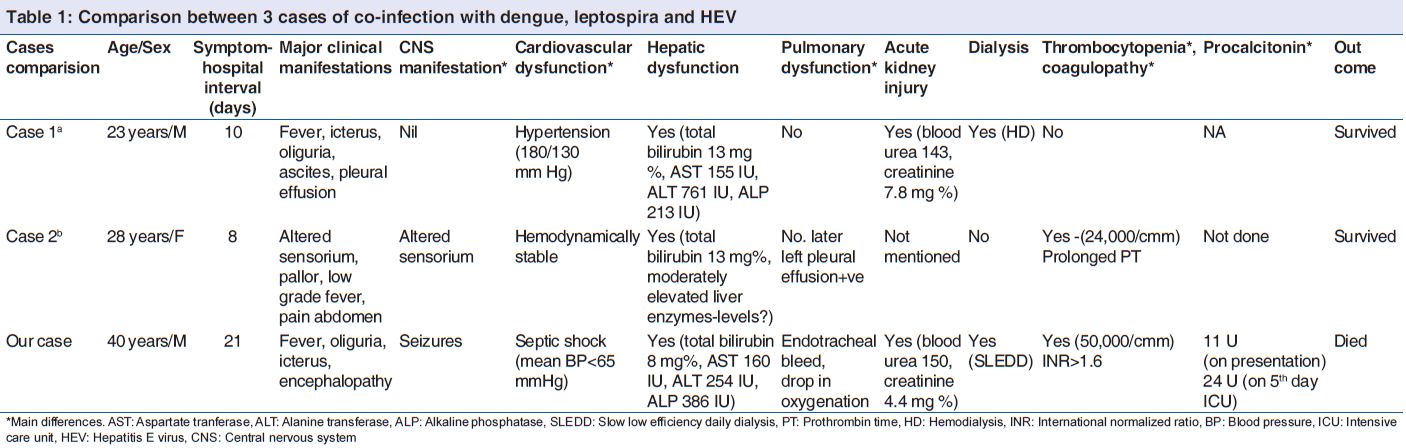

The markedly similar presentation and clinical course of infectious tropical illnesses as well as poor availability of diagnostic techniques prevent proper diagnosis of co-infections.[1] Here we report a case where we detected dengue, leptospirosis and hepatitis E virus (HEV) triple co-infection. Extensive literature search revealed that only two such case of co-infection is reported so far.[1,2] Both the previous cases survived but our case died. We are reporting our case along with review and comparison of these three cases.

Case Report

The present case report is about a 40-year-old businessman who was admitted to our intensive care unit (ICU) with a history of fever with chills for last 20 days and vomiting, seizures and decreased urine output for last 4-5 days. At the time of admission, he was in shock, intubated and on mechanical ventilation, icteric and had acute kidney injury are shown in Table 1. His acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II and sequential organ failure assessment scores were 22 and 17 respectively. His previous investigations reported positive for dengue antigen non-structural (NS1) but, negative for malaria and enteric fever. His hematocrit (35.2%) and total leukocyte count (9600/mm3) were normal. Major problems in ICU were coagulopathy with endotracheal bleed, anuria, progressively deteriorating liver function, ongoing septic shock. Multi-organ support was initiated in the form of lung protective mechanical ventilation, slow low efficiency daily dialysis, vasopressors (noradrenaline), broad spectrum antibiotics (ceftriaxone) and artesunate. He tested enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) positive for dengue immunoglobulin M (IgM; Dengue IgM capture ELISA, PanBio, Australia), Leptospira IgM (LeptoTek DriDot, Organon Teknika, Netherlands) and HEV IgM (Wantai-IgM, Wantai, China), while malaria, enteric fever, hepatitis A, B, C and human immunodeficiency virus tests were all negative. Serum procalcitonin showed rising trends with no growth of organisms from blood, endotracheal or urine samples. Despite organ supportive measures his condition deteriorated and he died on the 6th day of ICU stay. Family did not give consent for renal and liver biopsy.

Discussion

Our patient presented with acute febrile illness, thrombocytopenia, liver and renal dysfunction with dengue antigen positivity. Initially, in this patient, our target was to optimize fluid management by serial monitoring of hematocrit. We investigated for malaria, leptospirosis and enteric fever co-infection promptly. We started antibiotics and anti-malarial treatment in view of bacterial, spirochetal, malarial co-infection. However as is depicts in Table 1, delayed admission to ICU leading to delayed detection of co-infection, along with the presence of dual, i.e., hypovolemic and septic shock were the likely reasons for mortality in our case as against the other two cases which were both hemodynamically stable.

The probable reasons for this triple co-infection in immunocompetent patient could be rapid urbanization, increasing population density, frequent travel, poor water drainage infrastructure and inadequate vector control measures.[2] Mortality and morbidity is high in such co-infection.[2] Mortality can be related with endothelial dysfunction in these co-infections. Antibodies against NS proteins of dengue virion can cross-react with endothelial cells, leading to expression of cytokine, chemokines and adhesion molecules, activation of T-lymphocytes and dysfunction of the hemostatic system.[3] Associated thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy may also be seen. Pathogenesis of severe form of leptospirosis (Weil’s diseases and severe pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome) is believed to be due to generalized endothelial dysfunction.[4,5] Similar to sepsis, lipopolysaccharide and glycolipoprotein of leptospira interrogans are known to activate leukocytes leading to production of tumor necrosis factor alpha-α and/or interleukin-8 like pro-inflammatory cytokines.[5] As in sepsis, these pro-inflammatory cytokines lead to increased production of nitric oxide, thus heralding endothelial and renal dysfunction.[4,5] HEV infection can result in cerebral edema and disseminated intravascular coagulation.[6]

Microscopic agglutination test is the gold standard serologic test for detection of leptospira and it is not easily available in our country. Hence we have to rely upon positive IgM ELISA test for leptospira, which is 100% sensitive and 93% specific[7] in reaching the diagnosis of leptospira co-infection. However, as it’s an indirect screening test false positive results may be present.[7] Regarding the diagnosis of HEV infection, IgM ELISA for HEV (Wantai-IgM ELISA) was done on a single serum sample due to deranged liver profile. This test is reportedly 83-98% sensitive and 95.3-100% specific.[8] But recent literature tells us that even the HEV IgM ELISA testing can lead to diagnostic mistakes from polyclonal activation of specific B-cell clones lead by viruses such as cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus.[9] A full confirmation of the HEV co-infection would require a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing and demonstration of HEV ribonucleic acid (RNA) viremia.[9] In addition, RT-PCR for HEV RNA was not done in any of these three cases [Table 1]. This we must state a limitation of this report.

However, since the patient arrived late in the course of illness with already established and on-going hypovolemic and septic shock and multi-organ dysfunction, generalized endothelial involvement was already worsening. Initiation of early treatment could have prevented onset and progression of endothelial dysfunction if the patient was appropriately managed early in the course of illness.

The possibility of triple co-infection even in immunocompetent individuals is highlighted in this case report. We also emphasize through this three case review that early detection of such co-infected cases as well as early initiation of therapy can possibly defer early endothelial involvement and alter the outcome favorably.

Source of Support

Nil.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Behera B, Chaudhry R, Pandey A, Mohan A, Dar L, Premlatha MM, et al. Co-infections due to leptospira, dengue and hepatitis E: A diagnostic challenge. J Infect Dev Ctries 2009;4:48-50.

- Chaudhry R, Pandey A, Das A, Broor S. Infection potpourri: Are we watching? Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2009;52:125.

- Basu A, Chaturvedi UC. Vascular endothelium: The battlefield of dengue viruses. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2008;53:287-99.

- Maciel EA, Athanazio DA, Reis EA, Cunha FQ, Queiroz A, Almeida D, et al. High serum nitric oxide levels in patients with severe leptospirosis. Acta Trop 2006;100:256-60.

- Yang GG, Hsu YH. Nitric oxide production and immunoglobulin deposition in leptospiral hemorrhagic respiratory failure. J Formos Med Assoc 2005;104:759-63.

- Panda SK, Thakral D, Rehman S. Hepatitis E virus. Rev Med Virol 2007;17:151-80.

- Kaur IR, Sachdeva R, Arora V, Talwar V. Preliminary survey of leptospirosis amongst febrile patients from urban slums of East Delhi. J Assoc Physicians India 2003;51:249-51.

- Zhou H, Jiang CW, Li LP, Zhao CY, Wang YC, Xu YW, et al. Comparison of the reliability of two ELISA kits for detecting IgM antibody against hepatitis E virus. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2008;42:667-71.

- Fogeda M, de Ory F, Avellón A, Echevarría JM. Differential diagnosis of hepatitis E virus, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection in patients with suspected hepatitis E. J Clin Virol 2009;45:259-61.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.