Hepatitis-B Vaccination Status Among Dental Surgeons in Benin City, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Azodo Clement Chinedu

Department of Periodontics, University of Benin Teaching Hospital, P. M. B. 1111 Ugbowo, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria.

E-mail: clementazodo@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background: The development of success-oriented hepatitis-B vaccine uptake approach among dental surgeons is dependent on the availability of comprehensive baseline data. Objective: To determine the hepatitis-B vaccination status among dental surgeons in Benin City. Materials and Methods: This questionnaire-based cross-sectional study of dental surgeons in Benin City was conducted in May 2011. The questionnaire elicited information on demography, occupational risk rating of contracting hepatitis-B infection, hepatitis-B vaccination status, barriers to uptake of hepatitis vaccine, and suggestions on how to improve hepatitis-B vaccination rates among dental surgeons. Results: Participation rate in the study was 93.3%. More than half (51.4%) of the respondents were 20–30 years old and 52 (74.3%) were males. The occupational risk of contracting hepatitis-B infection among dental surgeons was rated as either high or very high by 51 (72.9%) of the respondents. Amongst the respondents, 14 (20.0%) had received three doses of the hepatitis-B vaccine, 34 (48.6%) either two doses or a single dose, and 22 (31.4%) were not vaccinated. The major barriers reported among the respondents who were not vaccinated were lack of opportunity and the fear of side effects of the vaccines. The suggested ways to increase the vaccination rate among the respondents in descending order include: Making the vaccine available at no cost (51.4%), educating dentists on the merits of vaccination (17.1%), and using the evidence of vaccination as a requirement for annual practicing license renewal (14.3%) and for the employment of dental surgeons (11.4%) and others (2.9%). Conclusion: This study revealed low prevalence of complete hepatitis-B vaccination among the respondents. Improvement in uptake following the respondents’ recommendations will serve as a template in developing success-oriented strategies among stakeholders.

Keywords

Dental surgeon, Hepatitis-B, Vaccination status

Introduction

Hepatitis-B vaccine, developed for the prevention of hepatitis-B virus infection, is a noninfectious recombinant DNA vaccine produced from genetically engineered yeast named Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[1] Although there has been modification in the production of the vaccine after its initial development in 1981, the complete vaccination still remains the uptake of the recommended three-dose regimen, with the second and third doses being given at 1 and 6 months after the initial dose.[2,3] Despite the availability and recommendation on hepatitis-B vaccination, the vaccination rates among dental professionals have remained consistently low in developing countries. The reasons for the suboptimal hepatitis-B vaccination rates among health workers include lack of opportunity, lack of motivation, lack of information, lack of awareness, non-availability, high cost of the vaccine, fear of side effects, fear of being recognized as a hepatitis-B carrier, lack of perceived need for the vaccine, and erroneous belief of non-susceptibility to the infection.[4-16] There also existed no consensus about vaccination rates among dental professionals in the literature as dental surgeons had higher vaccination rates than dental auxiliaries in some studies[15] while dental auxiliaries had higher vaccination rates than dental surgeons in others.[17]

Although information about hepatitis-B vaccination status of dentists in Nigeria is available from studies conducted among dental professionals as a group[15,18] and dental surgeons in different parts of Nigeria exclusively,[19,20] the gaps in knowledge that motivated this present study exist in four specific areas. Firstly, the data on hepatitis-B vaccination status of dental surgeons in Benin City could not be abstracted from these studies, thereby limiting their utilization in developing success-oriented vaccine uptake approach. Secondly, these reports also lacked details about incomplete and complete hepatitis-B vaccination dose uptake. Thirdly, most of these studies were conducted among dental professionals working in the tertiary dental healthcare facilities while other members of staff of secondary and primary dental healthcare facilities were not studied. Finally, the improvement of uptake of hepatitis-B vaccination study has also been neglected in these studies. The potential risk of acquisition of hepatitis-B infection through occupational exposures to blood and its products among dental surgeons and the significant prevalence of hepatitis-B infection in Benin City[21] are the additional reasons for hepatitis-B vaccination research among dental surgeons practicing in this environment. The objective of the study was to assess the hepatitis-B vaccination status among dental surgeons in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study of dental surgeons in Benin City was conducted in May 2011, using pretested, 8-itemed, self-administered questionnaire as the tool of data collection. The questionnaire elicited information on demography, occupational risk rating of contracting hepatitis-B infection, hepatitis-B vaccination status, barriers to uptake, and suggestions on how to improve hepatitis-B vaccination rates among dental surgeons. The hand-delivered questionnaires were distributed to dental surgeons working at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital and Central Hospital, Benin City. Other dental surgeons were given the questionnaire at a dental product launch in Benin City. Participation in the study was voluntary and no incentive was offered. Informed consent was obtained from participants after informing them of the objective of the study. The data collected were subjected to descriptive statistics in the form of frequency and percentages using SPSS version 17.0. Test of association was done using Fisher’s exact statistics. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

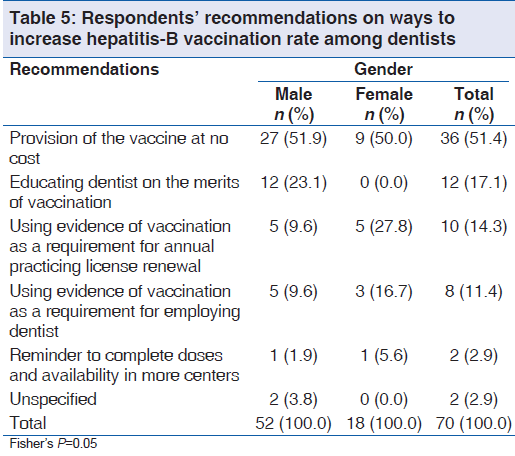

Participation rate in the study was 93.3%. More than half (51.4%) of the respondents were in the 20–30 years age group and 52 (74.3%) were males [Table 1]. The occupational risk of contracting hepatitis-B infection among dental professionals was rated as either high or very high by 51 (72.9%) of the respondents [Table 2]. Amongst the respondents, 14 (20.0%) had received three doses of the hepatitis-B vaccine, 34 (48.6%) either two doses or a single dose, and 22 (31.4%) were not vaccinated [Table 3]. The major barriers reported among the respondents who were not vaccinated were lack of opportunity and the fear of the side effects of the vaccine [Table 4]. The suggested ways to increase the vaccination rate among the respondents in descending order include: Making the vaccine available at no cost (51.4%), educating dentists on the merits of vaccination (17.1%), and using the evidence of vaccination as a requirement for annual practicing license renewal (14.3%) and for the employment of dental surgeons (11.4%). Others (2.9%) suggested that reminders to complete the vaccination should be sent and that the vaccines should be made available in more centers [Table 5].

| Characteristics | Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 21–30 | 23 (44.2) | 13(72.2) | 36 (51.4) |

| 31–40 | 20 (38.5) | 5 (27.8) | 25 (35.7) |

| >40 | 9 (17.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (12.9) |

| Years of | |||

| experience | |||

| >5 | 30 (57.7) | 16(88.9) | 46 (65.7) |

| 5–10 | 7 (13.5) | 1(5.6) | 8 (11.4) |

| <10 | 15 (28.8) | 1(5.6) | 16 (22.9) |

| Know HBV- | |||

| infected individual | |||

| Yes | 14 (26.9) | 3 (16.7) | 17 (24.3) |

| No | 38 (73.1) | 15(83.3) | 53 (75.7) |

| Total | 52 (100.0) | 18 (100.0) | 70 (100.0) |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the respondents

| Rating of occupational risk | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | ||||

| Very high | 15(28.8) | 7(38.9) | 22(31.4) | |||

| High | 21(40.4) | 8(44.4) | 29(41.4) | |||

| Moderate | 7 | (13.5) | 1 (5.6) | 8(11.4) | ||

| Low | 5(9.6) | 2(11.1) | 7(10.0) | |||

| Very low | 4(7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4(5.7) | |||

| Total | 52(100.0) | 18(100.0) | 70(100.0) | |||

Table 2: Respondents’ rating of occupational risk of Hepatitis-B contagion among dental surgeons

| Vaccination | Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | |||

| Three doses | 9(17.3) | 5(27.8) | 14(20.0) | ||

| Two doses | 14(26.9) | 6(33.3) | 20(28.6) | ||

| One dose | 10(19.2) | 4(22.2) | 14(20.0) | ||

| Unvaccinated | 19(36.5) | 3(16.7) | 22(31.4) | ||

| Total | 52(100.0) | 18(100.0) | 70 (100.0) | ||

Table 3: Hepatitis-B vaccination status among the respondents

| Barrier | Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | |

| Lack of opportunity | 6(31.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6(27.3) |

| Fear of side effects | 2(10.5) | 2 (66.7) | 4(18.2) |

| Low risk of contracting HBV infection | 3(15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3(13.6) |

| Never given it a thought | 2(10.5) | 1 (5.6) | 3(13.6) |

| Lack of information | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| Unspecified | 5(26.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5(22.7) |

| Total | 19(100.0) | 3 (100.0) | 22(100.0) |

Table 4: Reasons for non-vaccination among the unvaccinated respondents

Discussion

In this study, the perceived occupational risk of contracting hepatitis-B infection among dental surgeons was rated as either high or very high by majority of the respondents. This was comparable to the 78% of Malaysian dental practitioners who believed that their risk of contracting hepatitis B was high or very high[7] and 66.6% among Malaysian dentists.[22] This rating may be rooted on the high transmissibility potential of hepatitis-B virus in comparison to other blood-borne pathogens.[23] The frequent exposure to blood and body fluid of patients and the prevalent inadequate infection control practices noted among dental surgeons in developing countries may have contributed to this level of risk perception among the respondents in this study.

In this study, the percentage of the respondents who had received three doses (complete dose) of the hepatitis-B vaccine is lower than 86% reported among health workers in tertiary care hospital, Karachi;[24] 85.7% reported among dental professionals of the Military Hospital, Riyadh;[25] 73.8%[26] and 74.9% among Brazilian dentists;[10] 60% reported among healthcare worker in Lahore;[12] 56.2% reported among Italian dentists;[27] and 35.9% reported among Lithuanian general dental practitioners.[28] The percentage of complete hepatitis vaccination among dentists in Benin City in this study was also lower than the figures reported in other Nigerian studies. Previously, 53.8% was reported among healthcare workers in a tertiary hospital in southwest Nigeria[28] and 48.1% was reported among dental practitioners in Lagos, Ibadan, Ife, and Benin.[20] It has been reported that healthcare workers in Nigeria, who are expected to have high knowledge of and exposure to hepatitis-B infection, showed the greatest apathy to the vaccination program, and this is a possible explanation for the result from this study.[29] The fact that more than threequarters of the respondents did not know anybody infected with hepatitis B may have deterred them from viewing this disease as serious, and therefore makes them lack the motivation to be vaccinated. Also, the vaccine was made available to the healthcare workers at no cost in most of the previous studies and this may account for the higher percentage of vaccinated health workers.

This study found a higher level of incomplete vaccination when compared with the results of several other previous studies.[10,12,20,24] It therefore means that dental surgeons should not only be encouraged to receive hepatitis-B vaccine but also be encouraged to complete the dose to ensure the effectiveness of this vaccine. Those with incomplete vaccination status should also be encouraged to have anti-HBs titers measured to determine their level of protection and if there will be a need for a further dose of the vaccine. A few of the respondents in this study recommended that a reminder system should be developed to ensure the complete uptake of the vaccine [Table 5].

The percentage of the respondents who were not vaccinated in this study is comparable to 32% reported among Malaysian dental practitioners,[7] but higher than 27.7% reported among health workers in India,[30] 22% documented among healthcare workers in Lahore,[12] and 10% documented among dentists living in Montes Claros, southeast Brazil.[10] However, it is lower than 50.8% and 37% reported among Lithuanian general dental practitioners[28] and dental healthcare workers in Korea,[31] respectively. The fact that most of the respondents in this study were young and had fewer years of practice may be responsible for the low rate of vaccination as Olubuyide et al.[32] in a study among Nigerian doctors and dentists reported that unvaccinated personnel were more likely to be surgeons or dentists less than 37 years of age and had fewer years of professional activity.

There is an association between hepatitis-B virus infection and lack of hepatitis-B vaccination among healthcare personnel.[32,33] This makes the improvement of hepatitis-B vaccine uptake among the studied dental surgeons very important. In this study, one of the major barriers reported among the unvaccinated respondents was lack of opportunity. This tallied with the findings of Ibekwe and Ibeziako[11] and Okeke et al.[13] who reported lack of opportunity as their major reason for non-vaccination among health workers and medical students in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Fear of the side effects of the vaccine was also a major barrier to hepatitis-B vaccination in this study and this is similar to findings of several studies in Greater Glasgow Area Health Board,[5] Malaysia,[7] Rhode Island,[4] and United States.[6] Doebbeling et al.[34] also reported that the concern about vaccine’s side effects and problems with vaccine access were primarily related to refusal. This is hinged on the fact that perception of vaccine safety is the most important predictor for acceptance of hepatitis-B vaccination among health workers.[35] Other previously reported reasons like lack of information,[7] lack of perceived need for the vaccine,[6] belief that they were not at risk,[9] and never giving it a thought[13] were also among the findings in this study.

In this study, the most commonly suggested way to increase the vaccination rate among the respondents was making the vaccine available at no cost. Sheikh et al.[12] suggested that hepatitis-B vaccine should be made available to healthcare workers at no cost. McGrane and Staines[14] documented that the provision of free vaccine to healthcare workers had a strong positive influence on their decision to be vaccinated. Educating dentists on the merits of vaccination was the second most commonly suggested way of improving hepatitis-B vaccination among the dental surgeons in this study. This recommendation is expected to reasonably improve uptake since dissemination of information resulted in significantly improved knowledge and attitudes and acceptance rates among hospital personnel in a previous study.[36] Acceptance of vaccination has been said to improve with improved knowledge of hepatitis B and improved confidence in vaccine efficacy and safety among hospital personnel.[37]

The suggestion from this study that evidence of vaccination should be used as a requirement for annual practicing license renewal and employing dentists implies that vaccination should be mandatory. This mandatory recommendation has also been suggested in several studies.[12,15,38] The recommendation was significantly associated with gender, with female dental surgeons recommending mandatory vaccination more than males. The better preventive health practices among females may have inclined them to recommending mandatory vaccination in this study.

Conclusion

This study revealed high perception of occupational risk of hepatitis-B virus infection and low hepatitis-B vaccination among the respondents. It is expected that the combination of the recommendations would overcome all the documented barriers and result in 100% uptake of vaccination among the dental surgeons in Benin City. This will serve as a template in developing success-oriented strategies among stakeholders.

Acknowledgment

The abstract of this study was presented under the Senior Clinical Research Category of the Hatton poster competition in the 3rd African Middle East Conference of International Association for Dental Research that was held in Abuja, Nigeria, between 25 and 28 September, 2011. The authors are grateful to the dental surgeons whose participation made this research a success.

Source of Support

Nil.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Keating GM, Noble S. Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Engerix-B): A review of its immunogenicity and protective efficacy against hepatitis B. Drugs 2003;63:1021-51.

- Poland GA, Borrud A, Jacobson RM, McDermott K, Wollan PC, Brakke D, et al. Determination of deltoid fat pad thickness. Implications for needle length in adult immunization. JAMA 1997;277:1709-11.

- Poland GA, Jacobson RM. Clinical practice: Prevention of hepatitis B with the hepatitis B vaccine. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2832-8.

- Yacovone JA, Weisfeld J. Acceptance of hepatitis B vaccine by Rhode Island dental practitioners. J Am Dent Assoc 1985;111:65-7.

- Samaranayake LP, Lamey PJ, MacFarlane TW, Glass GW. Attitudes of general dental practitioners towards the hepatitis B vaccine. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1987;15:125-7.

- Echavez MI, Shaw FE Jr, Scarlett MI, Kane MA. Hepatitis B vaccine usage among dental practitioners in the United States: An epidemiological survey. J Public Health Dent 1987;47:182-5.

- Yaacob HB, Samaranayake LP. Awareness and acceptance of the hepatitis B vaccine by dental practitioners in Malaysia. J Oral Pathol Med 1989;18:236-9.

- Adebamowo CA, Ajuwon A. The immunization status and level of knowledge about hepatitis B virus infection among Nigerian surgeons. West Afr J Med 1997;16:93-6.

- Nasir K, Khan KA, Kadri WM, Salim S, Tufail K, Sheikh HZ, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination among health care workers and students of a medical college. J Pak Med Assoc 2000;50:239-43.

- Martins AM, Barreto SM. Hepatitis B vaccination among dentists surgeons. Rev Saude Publica 2003;37:333-8.

- Ibekwe RC, Ibeziako N. Hepatitis B vaccination status among health workers in Enugu, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2006;9:7-10.

- Sheikh NM, Hasnain S, Majrooh A, Tariq M, Maqbool H. Status of hepatitis B vaccination among the health care workers of a tertiary hospital, Lahore. Biomedica 2007;23:17-20.

- Okeke EN, Ladep NG, Agaba EI, Malu AO. Hepatitis B vaccination status and needle stick injuries among medical students in a Nigerian university. Niger J Med 2008;17:330-2.

- McGrane J, Staines A. Nursing staff knowledge of the hepatitis B virus including attitudes and acceptance of hepatitis B vaccination. Development of an effective program. AAOHN J 2003;51:347-52.

- Sofola OO, Uti OG. Hepatitis B virus infection and prevention in the dental clinic: Knowledge and factors determining vaccine uptake in a Nigerian dental teaching hospital. Nig Q J Hosp Med 2008;18:145-8.

- Hussain S, Patrick NA, Shams R. Hepatitis B and C prevalence and prevention awareness among health care workers in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Pathol 2010;8:16-21.

- Noble MA, Mathias RG, Gibson GB, Epstein JB. Hepatitis B and HIV infections in dental professionals: Effectiveness of infection control procedures. J Can Dent Assoc 1991;57:55-8.

- Fasunloro A, Owotade FJ. Occupational hazards among clinical dental staff. J Contemp Dent Pract 2004;5:134-52.

- Sofola OO, Savage KO. Assessment of the compliance of Nigerian dentists with infection control: A preliminary study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003;24:737-40.

- Utomi IL. Attitudes of Nigerian dentists towards hepatitis B vaccination and use of barrier techniques. West Afr J Med 2005;24:223-6.

- Abiodun PO, Olomu A, Okolo SN, Obasohan A, Freeman O. The prevalence of hepatitis Be antigen and anti-HBE in adults in Benin City. West Afr J Med 1994;13:171-4.

- Razak IA, Latifah RJ, Nasruddin J, Esa R. Awareness and attitudes toward hepatitis B among Malaysian dentists. Clin Prev Dent 1991;13:22-4.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Immunization of Health care workers; Recommendation of advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) and the Hospital infection control practices advisory committee (HICPAC). MMWR Recomm Rep 1997;46:1-42.

- Ali NS, Jamal K, Qureshi R. Hepatitis B vaccination status and identification of risk factors for hepatitis B in health care workers. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2005;15:257-60.

- Paul T. Self-reported needlestick injuries in dental health care workers at armed forces hospital Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Mil Med 2000;165:208-10.

- Resende VL, Abreu MH, Paiva SM, Teixeira R, Pordeus IA. Concerns regarding hepatitis B vaccination and post-vaccination test among Brazilian dentists. Virol J 2010;7:154.

- Di Giuseppe G, Nobile CG, Marinelli P, Angelillo IF. A survey of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of Italian dentists toward immunization. Vaccine 2007;25:1669-75.

- Rimkuviene J, Puriene A, Peciuliene V, Zaleckas L. Percutaneous injuries and hepatitis B vaccination among Lithuanian dentists. Stomatologija 2011;13:2-7.

- Fatusi AO, Fatusi OA, Esimai AO, Onayade AA, Ojo OS. Acceptance of hepatitis B vaccine by workers in a Nigerian teaching hospital. East Afr Med J 2000;77:608-12.

- Sukriti, Pati NT, Sethi A, Agrawal K, Agrawal K, Kumar GT, et al. Low levels of awareness, vaccine coverage, and the need for boosters among health care workers in tertiary care hospitals in India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:1710-5.

- Song KB, Choi KS, Lang WP, Jacobson JJ. Hepatitis B prevalence and infection control among dental health care workers in a community in South Korea. J Public Health Dent 1999;59:39-43.

- Olubuyide IO, Ola SO, Aliyu B, Dosumu OO, Arotiba JT, Olaleye OA, et al. Hepatitis B and C in doctors and dentists in Nigeria. QJM 1997;90:417-22.

- Thomas DL, Factor SH, Kelen GD, Washington AS, Taylor E Jr, Quinn TC. Viral hepatitis in health care personnel at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. The seroprevalence of and risk factors for hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:1705-12.

- Doebbeling BN, Ferguson KJ, Kohout FJ. Predictors of hepatitis B vaccine acceptance in health care workers. Med Care 1996;34:58-72.

- Topuridze M, Butsashvili M, Kamkamidze G, Kajaia M, Morse D, McNutt LA. Barriers to hepatitis B vaccine coverage among healthcare workers in the Republic of Georgia: An international perspective. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010;31:158-64.

- Kamolratanakul P, Ungtavorn P, Israsena S, Sakulramrung R. The influence of dissemination of information on the changes of knowledge, attitude and acceptance of hepatitis B vaccination among hospital personnel in chulalongkorn hospital. Public Health 1994;108:49-53.

- Israsena S, Kamolratanakul P, Sakulramrung R. Factors influencing acceptance of hepatitis B vaccination by hospital personnel in an area hyperendemic for hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:1807-9.

- Chaudhari CN, Bhagat MR, Ashturkar A, Misra RN. Hepatitis B vaccination status among health care workers. Medical J Armed Forces India 2009;65:13-7.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.