Institutional Delivery Service Utilization and Its Associated Factors among Women Who Gave Birth during the Past One Year in Mizan Aman City Administration, Bench Maji Zone, South West Ethiopia, 2017

Citation: Daniel A, et al. Institutional Delivery Service Utilization and Its Associated Factors among Women Who Gave Birth during the Past One Year in Mizan Aman City Administration, Bench Maji Zone, South West Ethiopia, 2017. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2018;8:54-61

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Maternal mortality due to unsafe abortion, prolonged labour, eclampsia and other reasons has been the major problem across the globe especially in developing countries. This is because; most of those deliveries occur outside health care facilities and assisted with nonprofessionals. Aim: To assess magnitude and factors associated with institutional delivery practice and its determinants among mothers who gave birth during the past one year in Mizan Aman Town, Bench Maji zone, South West Ethiopia. Methods and Materials: Community based cross sectional study was conducted among mothers who gave birth during the past one year from April 10 to May 10, 2017. Structured and pretested questionnaire was used for data collection. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 20 software. Crude and adjusted Odds ratios were computed for selected variables and P-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistical significant. Results: Only 54.2% of mothers gave birth at health facilities. Husbands educational level, decision about the cost related to health care/for referral or reaching health facility and place of antenatal care follow up were associated with institutional delivery service utilization. Conclusion: In contrast to studies conducted in other parts of the country and the Ethiopia Demographic health survey result of 2016, the number of women who had given birth at health care facilities in Mizan Aman city administration was higher. However, it was below the health sector transformation plan of the country that has a plan to raise institutional delivery supported by health personnel to 95%. Thus increasing awareness of mothers and their partners about the benefits of institutional delivery services are recommended.

Keywords

Institutional delivery; Women; Birth; Mizan Aman; Ethiopia

Introduction

Maternal mortality due to various reasons has been the major problem across the globe especially in developing countries. It is reported that globally, about 289,000 women dies each year due to preventable causes, yielding a maternal mortality rate (MMR) of 210 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Some of identified factors considered as a major cause for maternal mortality are hemorrhage, infection, unsafe abortion, prolonged labour and eclampsia. [1] These identified causes are more common in condition where child delivery occur out of health institutions. This is because; most of those deliveries occur outside health care facilities are assisted with non-professionals which led to large proportion of maternal deaths which could be prevented if deliveries were overseen by skilled personnel. [2] For instance, many studies revealed that maternal mortality rate (MMR) is less 200 per 100,000 live births in countries where more than 80% of deliveries supported by health care professionals. [3]

A lot of strategies were developed and applied by many countries in order to reduce the burden of maternal death. Of those strategies, according to many evidences, a health center intra-partum care strategy can be considered as the foremost to reduce the rate of maternal mortality. [4] Also it is confirmed that proper utilization of health care services including institutional delivery is surely minimize the risk of maternal deaths and disabilities. [5] Other evidences showed that, the presence of skilled attendants at delivery and implementing skilled birth care services, estimated to decrease maternal deaths by 16% to 33% and this means approximately 20–30% of neonatal mortality. [1]

Even though proper care during pregnancy and delivery is important for the health of both the mother and the baby, there are problems regarding to coverage and utilization of institutional delivery services globally. The problem is common across the world, but there is observable difference in the distribution of maternal health care service utilization in developing and developed countries. For instance, a report from developed countries revealed that majority, 97% of the pregnant women receive antenatal care (ANC) service and almost all births (99%) use skilled obstetric service during delivery. On the contrary, in low income countries only 52% of pregnant women had four or more ANC visits during their pregnancy and skilled health personnel attended 68% of deliveries. Particularly, Sub-Saharan Africa is area with the lowest coverage of skilled delivery service utilization, with 53% of women having skilled delivery attendants. [6]

In Ethiopia Maternal deaths represent 25 percent of all deaths among women age 15-49 and current maternal mortality ratio is 412 per 100,000 live births. Most of this maternal death is attributed to poor utilization of institutional delivery services. Various studies in different parts of the country indicated that in Ethiopia, the utilization of health facilities for delivery service still at lower level in spite of a rapid health facility expansion throughout the country. [7] The 2011 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) report showed that, only 34% of women who gave birth in the five years earlier to the survey received antenatal care from skilled providers, who are health care professionals for their most recent birth. Even if the program design is uniform throughout the country, there is substantial regional variation in the utilization of health institutions for delivery and other maternal health services. For instance a finding from Afar revealed that it has the lowest percentage of women whose births were delivered by a skilled provider or delivered in a health facility (16 percent and 15 percent, respectively), while Addis Ababa has the highest coverage of institutional service utilization which is (97%). [8]

The contribution of improving institutional delivery service coverage for reducing maternal mortality in Ethiopia is unquestionable. Thus it is imperative to identify predictors of institutional delivery service utilization to design and apply appropriate intervention. However, there was shortage of data which reveals the current utilization status of institutional delivery and its associated factors in Mizan Aman city administration. Therefore, this study aimed at determining the magnitude and factors that affect institutional delivery service utilization in this area. The finding of this study would be an input for policy makers, planners and health managers to undertake proper intervention supported with evidence. Also it might be baseline data for Bench-Maji zone health department to undertake appropriate measures to enhance institutional delivery service utilization, in turn contributes for a considerable reduction of maternal mortality in this zone.

Objectives

General objective

To assess utilization status of institutional delivery service and its associated factors among mothers who gave birth during the past one year in Mizan Aman city administration, Bench Maji zone, South West Ethiopia.

Specific objectives

• To determine magnitude of institutional delivery among mothers who gave birth during the past one year in Mizan Aman city administration, Bench Maji zone, South West Ethiopia.

• To identify factors associated with institutional delivery among mothers who gave birth during the past one year in Mizan Aman city administration, Bench Maji zone, South West Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Study area and period

This study was conducted from April 10 to May 10, 2017 in Mizan Aman city administration. It is found in Bench Maji zone which is one of the 13 zones in the Southern, Nations, Nationalities and People’s Regional (SNNPR) of Ethiopia and located in the western part of the region. Mizan Aman is the capital town of this Zone, which is situated 561 Km far away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of the country. The total population of Mizan-Aman district is 50,113, of which 24,956 are males and 25,157 are females. Women of reproductive age group (15-49 years) in the town were 7,853 according to annual population report. The District is structured in such a way that it has two Kifle Ketema (administrative unit) with a total of 5 Kebeles (3 of them were in Mizan Kifle Ketema and the remaining 2 Kebeles in Aman Kifle Ketema). There is one general hospital, one health center and 5 health posts all run by the government. In the private sector there are 20 clinics (of which 5 are medium clinics), 20 drug distribution stores, and 1 drug venders.

Study design

Community-based cross-sectional survey was conducted to assess utilization of institutional delivery among women who gave birth during the past one year.

Source population

All women in reproductive age group (15-49) were found to be the source population for this study.

Study population

The study populations included in this study were all women who give birth in the past one year in Mizan Aman city administration.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated based on the assumptions of prevalence of institutional delivery (P), 22.4% from a recent study done in Afambo district, Afar region. [9], confidence level of 95% and 5% degree of marginal precision (d).

Where, N=sample size, P= proportion, d2=margin of error and Z ά /2 = the value of standard normal distribution corresponding to a significant level of alpha.

,

,

N=268

Non response rate 10% of the calculated sample size =268 (10/100) + 268= 268+26.8= 295. Therefore, the total sample size calculated for this study was, N=295.

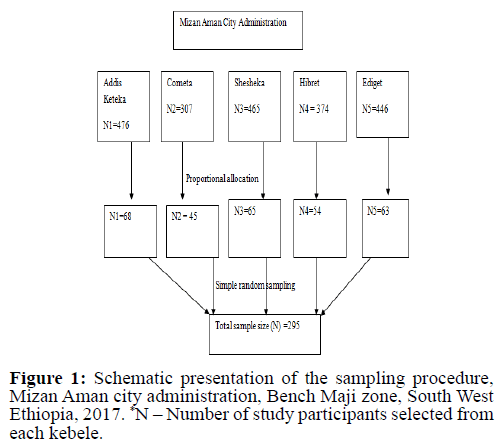

Sampling technique

The sample size was distributed to five (5) kebele proportionate to the size of mothers who gave birth at last one year. At each kebele level, mothers who delivered in the past one year, was selected by simple random sampling specifically lottery method based on sampling frame was obtained from kebele health extension worker [Figure 1].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: Those women who gave birth during the past one year and who lived in the study area for more than six months before the study period are included in this study.

Exclusion criteria: Those women who were mentally and physically ill or with other disabilities that might hinder communication were excluded from this study.

Data collection method

The data was collected by one female and two male 4th year graduate class public health students. Study participants were interviewed using structured questionnaire focused on variables including socio-demographic, obstetric, actual delivery and others. Data collection tools were prepared after reviewing relevant literatures and adopting from previous similar studies conducted before. The English version of the questionnaire was translated to Amharic language to understand easily by the study participants.

Study variables

Dependent variable

• Institutional delivery service utilization

Independent variables

• Socio-demographic factor (Age, economic status, marital status, religious, occupational status, ethnicity, educational status)

• Obstetric factors (Age at first marriage, age at first pregnancy, place of last delivery, complication of last pregnancy)

• Environmental factors (Transportation accessibility)

• Other decision related factors

Operational definition(s)

Institutional delivery service utilization: In this study, this means, when a mother gave birth at health institution (health center, hospital, or private clinic).

Home delivery: In this study, this means, when a mother gave birth at her home or others’ home (neighbor, relatives, or family) or when a birth takes place outside of health institution.

Close to health care facility: This study used the term close to health care facility “if a woman travelled <5 km to reach health care facility”.

Far from health care facility: This study used the term far from health care facility If a woman travelled >5km to reach health care facility.

Woman’s autonomy: If a woman decides on the place to give birth by herself or with her husband jointly.

Data quality control

To manage data quality principal investigators and supervisors check the completeness, consistency and accuracy of the data at the end of each day to make immediate correction if it was appropriate. Pre-testing of the questionnaires was made in the area that was not included in the main study before the actual data collection time.

Data analysis

Data was interred and analyzed using SPSS version 22 data software. Descriptive statistics was done and results are presented in tables and figures. Bi-variant and Multivariable analysis was carried out to test the association between independent and dependent variables.

Ethical consideration

Supportive latter was obtained from Department of Public Health, Collage of medicine and Health Sciences, Mizan Tepi University and it was communicated to Mizan-Aman city administration health office. Permission and verbal consent was obtained from each respondent during interview and confidentiality was also assured before commencing data collection process. Study participants were informed about the objective of the study and its benefit.

Dissemination of results

The research paper was presented and submitted for department of public health, College of medicine and health sciences, Mizan Tepi University. Finally, the copy was distributed to Mizan-Aman city administration and health office.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total number of 295 women’s who had delivered in the past one year were participated in the study, with 100% response rate. More than one third, 125 (42.4%), of them were aged greater than or equal to 35 years and the mean and standard deviation was 34.5 and 8.75 respectively. Almost all, 280 (94.9%), of participants were married and majority, 127 (43.1%), of them had educational level of above secondary school. Regardin ethnicity majority, 200 (67.8%), of them was Bench ethnic group. The rest 42 (14.2), 16 (5.4%), 16 (5.4%) and 12 (4.1%) of them were found to be Keffa, Oromo, Tigray and Amhara ethnic groups, respectively [Table 1].

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-19 | 38 | 12.9 |

| 20-24 | 61 | 20.7 | |

| 25-34 | 71 | 24.1 | |

| >=35 | 125 | 42.4 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 67 | 22.7 |

| Protestant | 184 | 62.4 | |

| Muslim | 40 | 13.6 | |

| Catholic | 4 | 1.4 | |

| Marital status | Married | 280 | 94.9 |

| Never married | 4 | 1.4 | |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Divorced | 9 | 3.0 | |

| Educational status of mother | Cannot read and write | 56 | 19.0 |

| Can read and write | 45 | 15.2 | |

| Primary education | 45 | 15.2 | |

| Secondary education | 22 | 7.5 | |

| Above secondary education | 127 | 43.1 | |

| Educational status of father (n=280) | Cannot read and write | 10 | 3.6 |

| Can read and write | 49 | 17.5 | |

| Primary education | 59 | 21.1 | |

| Secondary education | 37 | 13.2 | |

| Above secondary education | 125 | 44.6 | |

| Occupational status of mother | House wife | 189 | 64.1 |

| Government employee | 94 | 31.9 | |

| NGO-employee | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Private business | 9 | 3.0 | |

| Student | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Occupational status of father (n=280) | Farmer | 154 | 55.0 |

| Governmental employee | 82 | 29.3 | |

| NGO employee | 8 | 2.9 | |

| Daily laborer | 12 | 4.3 | |

| Private business | 23 | 8.2 | |

| Student | 1 | 0.3 |

*NGO-Non-Governmental Organization

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of women in Mizan-Aman city administration, Bench Maji zone, South West Ethiopia, 2017 (n=295).

Obstetric characteristics of respondents

From the total respondents only 48 (16.3%), of them had gave birth only once. Most, 157(53.4%), of the respondents’ age at first marriage was less than 18 years. Out of 295 respondents about 257 (87.1) had attained ANC and of those, 250 (97. 3%) of them had three or four visit and, 183 (71.2%) of them were attained at health center. Majorities, 232 (90.3%), gestational age at first ANC visit were first trimester. Nearly half, 135 (45.8%), of mothers delivered their previous child at home and of those who delivered at home only 12 (8.9%) were assisted by skilled personnel while nearly one third, 47 (34. 8%), of them assisted by relatives. From the total respondents 135 (47.8%) of them planned their place of delivery, while 160 (54.2%) of them did not have any plan towards their place of delivery. From those women who had planned their place of delivery, 71 (52.6%) of them preferred health institution and the rest 64 (47.4%) of them preferred home delivery [Table 2].

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at 1st marriage | <18 | 157 | 53.4 |

| >=18 | 137 | 46.6 | |

| Age at first pregnancy | <20 | 21 | 7.1 |

| >=20 | 274 | 92.9 | |

| Number of pregnancy (gravidity) | Primigravida | 48 | 16.3 |

| 2-4 | 133 | 45.1 | |

| >=5 | 114 | 38.6 | |

| Number of delivery (parity) | 1-3 | 244 | 82.7 |

| 4-6 | 50 | 17 | |

| >6 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Have you experienced prolonged labor | Yes | 250 | 84.7 |

| No | 45 | 15.3 | |

| Where did you delivered your previous last child | Home | 135 | 45.8 |

| Health care facility | 160 | 54.2 | |

| Who assisted you during delivery at home (n=135) | TBA | 34 | 25.2 |

| Skilled personnel | 12 | 8.9 | |

| Relatives | 47 | 34.8 | |

| Neighbor | 42 | 31.1 | |

| Was the pregnancy planned | Yes | 255 | 86.4 |

| No | 40 | 13.6 | |

| ANC visit | Yes | 257 | 87.1 |

| No | 38 | 12.9 | |

| Place of ANC attended | Health post | 8 | 3.1 |

| Health center | 183 | 71.2 | |

| Hospital | 66 | 25.7 | |

| Gestational week at 1st ANC visit | First trimester | 232 | 90.3 |

| Second trimester | 25 | 9.7 | |

| Number of ANC service | 1-2 | 8 | 3.1 |

| 3-4 | 250 | 96.9 | |

| From who you got ANC service | Midwives | 196 | 76.3 |

| Nurse | 4 | 1.6 | |

| Doctor | 15 | 5.8 | |

| Health officer | 35 | 13.6 | |

| Health extension workers | 7 | 2.7 | |

| Had bad obstetric history | Yes | 260 | 88.1 |

| No | 35 | 11.9 |

*ANC: Antenatal Care, TBA: Traditional Birth Attendant

Decision related and idea about institutional delivery

From the total 295 respondents, majority, 234 (79.3%), of the respondents’ discus about delivery place, the remaining, 61 (20. 7%), of the respondent were not discus about place of delivery. More than two third, 236 (80%), of the respondents prefers their place of delivery of last child to be at health facility. Half, 149 (50.5%), of study participants replied that decision regarding place of delivery made by both women and their husbands. Regarding decisions towards cost related to health care services more than half, 159 (53.9%) of them said both me and my husband, 97 (32.9%) of them replied as my husband, and the rest 68 (23.1%) of them said myself. Majority, 209 (70.8%), of the respondents were preferred to attend their last delivery by skilled birth attendant (SBA). While the rest 56 (19.0%) and 30 (10.2%) of them preferred to attend delivery by TTBA and family member, respectively. Based on the response of mothers most of them 158 (53. 9%), replied that decision regarding with cost related to health care service given by both wife and husband. Among the total respondents 249 (84.4%) of them know the necessity of institutional delivery. Majority, 192 (65.1%), of the respondents had got advice about their place of delivery and 171 (89.1%) of them got advice during ante-natal care service (ANC) follow up [Table 3].

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discuss about delivery place | Yes | 234 | 79.3 |

| No | 61 | 20.7 | |

| Preferred place of delivery during your last child | Home | 59 | 20.0 |

| Health facility | 236 | 80.0 | |

| Husband’s preferred place of delivery | Home | 82 | 27.8 |

| Health facility | 213 | 72.2 | |

| Your family preferred place of delivery during last child delivery | Home | 102 | 34.6 |

| Health facility | 193 | 65.4 | |

| Preferred place of neighbors during your last child birth | Home | 125 | 42.4 |

| Health facility | 170 | 57.6 | |

| Who was the one who made decision finally | Myself | 68 | 23.1 |

| My husband | 78 | 26.4 | |

| Both me and my husband | 149 | 50.5 | |

| What do you think regarding necessity of institutional delivery | Necessary | 249 | 84.4 |

| Not necessary | 46 | 15.6 | |

| Whom do you prefer to attend delivery | Skilled health care provider | 234 | 79.3 |

| TBA | 61 | 20.7 | |

| Did health provider explain your health condition | Yes | 208 | 80.9 |

| No | 49 | 19.1 | |

| Did health care provider explain what expected during delivery | Yes | 204 | 79.4 |

| No | 20.6 | ||

| Did health provider listen your questions and concern | Yes | 201 | 78.2 |

| No | 56 | 21.8 | |

| Did health provider respect you (n=257) | Yes | 189 | 73.5 |

| No | 68 | 26.5 | |

| Did you get advice about the need to have delivered at HCF | Yes | 192 | 65.1 |

| No | 103 | 34.9 | |

| When did you got advice (n=192) | During ANC visit | 171 | 89.1 |

| During home visit by HEW | 21 | 10.9 | |

| How do you rank the behavior of health care provider of ANC | Very good | 59 | 22.9 |

| Good | 150 | 58.4 | |

| Fair | 31 | 12.1 | |

| Bad | 17 | 6.6 |

*TBA-Traditional birth attendant, ANC-Antenatal care, HEWs, Health extension workers, HCF-Health care facility

Table 3: Decision about institutional delivery, perceptions about importance of institutional delivery and behavior of health care professionals among women in Mizan Aman city administration, Bench Maji zone, South West Ethiopia, 2017.

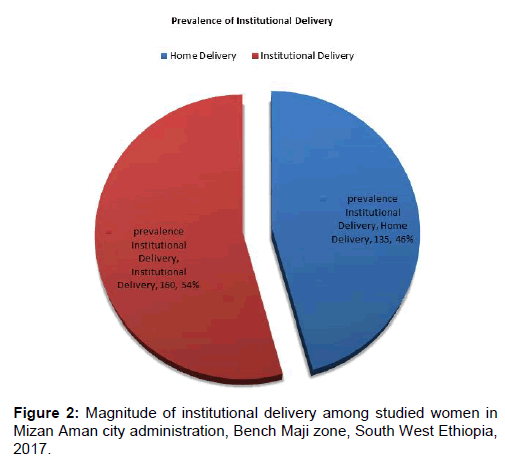

Prevalence of institutional delivery

Regarding the place of delivery, among 295 respondents more than half of respondents 160 (54.2%) delivered at health facility and the remaining respondents 135 (45.8%) were delivered at home [Figure 2].

Factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization

In this study, bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, level of education of women, husbands educational level, previous history of prolonged labor, from whom did you get ANC service, where did you get ANC service, decision about the cost related to health care/for referral or reaching health facility, advice about place of delivery, preference place of delivery during your last delivery and family preference place of delivery were statically associated with institutional delivery service utilization.

In multivariable logistic regression analysis husbands educational level, place of ANC service attended and decision about the cost related to health care/for referral or reaching health facility were positive association with institutional delivery service utilization(p<0.05) [Table 4].

| Variables | Category | Delivered in health institutions | Crude Odds Ratio (COR) (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Husband educational status | Can’t read and write | 25 | 49 | 0.711 (0.255, 1.98) | 1 |

| Primary education | 32 | 27 | 1.844 (0.691, 4.92) | 2.468 (0.671, 9.076)** | |

| Secondary education | 24 | 13 | 2.872 (0.98, 8.41) | 4.852 (1.186, 19.843) | |

| Above secondary education | 79 | 46 | 2.671 (1.072, 6.65) | 2.671 (1.072, 6.65) | |

| Place of ANC attended | Health post | 5 | 3 | 2 (0.441, 9.064) | 6.368 (1.102, 36.801)** |

| Health center | 106 | 77 | 1.652 (0.938, 2.911) | 2.324 (1.196, 4.516) | |

| Hospital | 30 | 36 | 1 | 1 | |

| Whom do you prefer to attend your delivery | Health care provider | 151 | 83 | 1.488 (0.691, 3.205)* | - - |

| TBA or family members | 9 | 52 | 0.556 (0.226, 1.367) | - | |

| Got advice regarding need of institutional delivery | Yes | 106 | 86 | 0.947 (0.538, 1.665)* | - |

| No | 35 | 30 | 1 | - | |

| From whom did you get ANC service | Midwife | 121 | 102 | 0.678 (0.193, 2.381) * | - |

| Nurse | 4 | 2 | 1.143 (0.141, 9.289) | - | |

| Doctor | 9 | 8 | 0.643 (0.136, 3.042) | - | |

| HEWs | 7 | 4 | 1 | - | |

| Educational status of mothers | Can’t read and write | 46 | 55 | 1.275 (0.58, 2.806) * | - |

| Primary education | 21 | 24 | 1.167 (0.53, 2.56) | - | |

| Secondary education | 10 | 12 | 1.11 (0.421, 2.997) | - | |

| Above secondary education | 44 | 83 | 2.515 (1.322, 4.785) | - | |

| Family preference place of delivery | Home | 42 | 60 | 2.929 (0.316, 27.182) * | - |

| Health facility | 118 | 75 | 6.293 (0.69, 57.38) | - | |

| Who decide on cost related to health care | Myself | 17 | 22 | 0.988 (0.467, 2.091) | 1 |

| My husband | 42 | 55 | 2.254 (1.107.4.586) | 0.944 (0.398, 2.241) ** | |

| Both | 101 | 58 | 0.773 (1.342, 8.564) | 2.735 (1.2, 6.236) | |

Â¥ ANC-antenatal care, HEWs-Health extension workers, TBA-Traditional birth attendants; *are variables which showed a significant association in Bivariate analysis; **are variables which showed a significant association in both bivariate and multivariate analysis

Table 4: Factors associated with institutional delivery among women in Mizan-Aman city administration, South-West Ethiopia, 2017.

Discussion

It is fact that there are a lot of factors affecting utilization of health services including not only availability, distance, cost, and quality of services, but also by socioeconomic factors and personal health beliefs. Thus it is imperative to describe the important factors associated with magnitude of institutional delivery service utilization to made evidence based intervention. [5] This study was intended to assess magnitude and factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization among mothers who gave birth in the past one year.

Obstetric care from a trained provider during delivery is recognized as critical for the reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality. Because, births delivered at a health facility are more likely to be delivered by a trained health professional. [7] According to the finding from this study considering the last delivery, the prevalence of institutional delivery service utilization or a mother who had gave birth at health institution was 54.2%. This finding was consistent with study finding in Woldyia [10] and Tigray region [11] with magnitude of institutional delivery of (48.3%) and (54%) respectively (36, 43). On the other side it was higher than the study finding from Sekela woreda of west Gojjam (12.1%), [12] Arbaminch area (20.6%) [13] and EDHS report of 2016 (26%). [7] The finding was also lower than a result obtained from a study done in Bahir Dar city, Amhara region where the magnitude of institutional delivery was 78.8%. [14] This discrepancy might be resulted due to difference in study period, sample size, study area, and sociodemographic characteristics of study participants.

Different studies confirmed that the probability of giving birth at health care facilities could be affected by a number of factors including place of residence, mother’s demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, and availability and quality of health services. [15] In this study the multivariate logistic regression analysis result revealed that husbands educational level, place of ANC service attended and decision on cost related to health care services were showed a significant association with institutional delivery service utilization

This study identified that educational status of husbands had a significant contribution for maternal utilization of health care institutions for delivery. Mother whose husband had completed secondary education was more than five times more likely to deliver at health institution than those mothers whose husbands can’t write and read. Also women whose husbands had above secondary educated were four times more likely to deliver in health facility. This finding was coherent with a result obtained in Bangladesh [16] and Goba woreda, Oromia region. [17] The possible justification for this could be educated husbands might have better understanding about complication of home delivery and benefit of institutional delivery and assist their partner in deciding on the place of delivery. Similarly, educated husbands could more open toward modern medicine and aware of the benefit of giving birth at health facility.

Women autonomy to decide on costs required for health care services had a significant contribution to choose the place where they need to give birth. The finding of this study showed that women who decide on the cost related to health care together with their husband were three times more likely to deliver in health facility than those without ability to participate in decision making with their husbands equally. This might be attributed to the possible presence of open communication about health care seeking behavior and stronger relationship with their husband as a result of the above factor mentioned.

Antenatal services can provide opportunities for women to get information on the status of their pregnancy which in turn alerts them to decide where to deliver. In addition, use of ANC may signify the availability of a nearby health care service, which may also provide delivery care. [18] Surprisingly, the finding from this study also revealed as ANC service would enhance mothers’ utilization of health care facilities for delivery. It showed that, women who attend ANC follow up at health post were six times more likely to deliver in health facility than those who attend ANC at hospital. This might be due to good intimacy with health extension workers (HEWs) and house to house health education about institutional delivery by HEWs. On the other hand, women who attend ANC at health center were two times more likely to deliver in health facility than those who attend in hospital. This finding was coherent with a result obtained from Tigray region. [19] This might be due to provision of attractive service and low waiting time.

Conclusion

In contrast to studies conducted in other parts of the country and the Ethiopia Demographic health survey (EDHS) result of 2016, the number of women who had given birth at health care facilities in Mizan Aman city administration was higher. However, it was below the health sector transformation (HSTP) plan of the country that have a plan to raise institutional delivery supported by health personnel to 95%. Husband’s level of education, decision about the cost related to health care/for referral or reaching health facility and place of anti natal care (ANC) follow up were factors significantly associated with institutional delivery service utilization.

Recommendations

Based on the result of this study recommendations are made for various concerned stakeholders. Enhancing educational status of father is one important factor believed to increase magnitude of institutional delivery. To strength heath extension programs, increase number of health extension workers and enhance the capacity health extension workers with different trainings. It was also recommended that health care provider should create good relationship with ante natal care (ANC) client and should give health education about significance of ANC service utilization.

Limitation to the Study

Since the study design for this research was a cross sectional study it might not show cause and effect relationship. It was good, if it was supplemented with focused group discussion.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no competing interest regarding the publication of this paper titled utilization status of institutional delivery and its predicting factors among women who gave birth during the past one year in Mizan Aman City Administration, Bench Maji Zone, and South West Ethiopia.

Acknowledgements

First of all we want to acknowledge collage of health sciences, Mizan Tepi University for their immense contribution to do this research with various aspects. Our thanks also go to all staffs of public health department for their cooperation during the process of finalizing this research.

Last but not least we would like to acknowledge all of the study participants for their willingness to provide the necessary information required for this study.

REFERENCES

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. The World Bank and United Nation Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality; 1990 to 2013.

- United Nation and African Union. Report on progress in achieving the millennium development goals in Africa. Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire; 2013.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Material Mortality updates; 2004. Delivering into Good Hands.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Safe motherhood technical consultation, Colombo, 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

- WWW.cdedse.org/ws2011/papers/ambris.

- United Nations (UN). The Millennium Development Goals Report. New York, USA; 2014.

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: DHS Program ICF Rockville, Maryland, USA; 2016.

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopia and ICF International Calverton Maryland; 2016.

- Mohammed MJ, Mohammed YE, Reddy PS. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers in Afambo district, Afar, Ethiopia. Med. Res. Chron. 2017;4:363-379.

- Awoke W, Mohammed J, Abeje G. Institutional delivery service utilization in Woldia, Ethiopia. Science Journal of Public Health. 2013;1:18-23.

- Tsegaye G. Determinants of antenatal and delivery care utilization in Tigray region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12.

- Teferra AS, Alemu FM, Woldeyohanes SM. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gavebirth in the last 12 months in Sekela District, North West of Ethiopia: A community - based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2012;12.

- Ayele G, Tilahun M, Merdikyos B, Animaw W, Taye W. Prevalence and associated factors of home delivery in Arbaminch Zuria district, southern Ethiopia: Community based cross sectional study. Science Journal of Public Health. 2015;3: 6-9.

- Abeje G, Azage M, Setegn T. Factors associated with Institutional delivery service utilization among mothers in Bahir Dar City administration, Amhara region: A community based cross sectional study. BMC Reproductive Health. 2014;11.

- Sugathan KS, Mishra V, Ratherford RD. Promoting institutional deliveries in rural India: The role of antenatal-care services, in national family health survey subject reports. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2011.

- Nazrul I, Mohammed TI, Yuke Y. Practices and determinants of delivery by skilled birth attendants in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health. 2014;11.

- Odo DB, Shifti DM. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among child bearing age women in Goba Woreda, Ethiopia. Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2014;2:63-70.

- Mpembeni RN, Killewo JZ, Leshabari MT, Massawe SN, Jahn A, Mushi D, et al. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in Southern Tanzania: Implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:1-7.

- Melaku YA, Weldearegawi B, Tesfay FH, Abera SF, Abraham L, Aregay A, et al. Poor linkages in maternal health care services? Evidence on antenatal care and institutional delivery from a community-based longitudinal study in Tigray region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14:418.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.