Perimenopausal Women Distressing from Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: A Philippine Quality of Life Assessment-Based Correlational Study

1Department of Nursing, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Majmaah University, Al-Majmaah, 11952, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2College of Nursing, Angeles University Foundation, Angeles, 2009, Philippines

3Department of Community Medicine and Public Health, College of Medicine, Majmaah University, Al-Majmaah, 11952, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

4Department of Health Administration, Al-Ghad International College of Applied Medical Sciences, Dammam, 31433, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Evelyn E. Feliciano

Department of Nursing

College of Applied Medical Sciences

Majmaah University

Al-Majmaah, 11952, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Tel: +966500497142

E-mail: e.feliciano@mu.edu.sa

Citation: Feliciano EE, et al. Perimenopausal Women Distressing from Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: A Philippine Quality of Life Assessment-Based Correlational Study. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2020; 10: 838-845.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Abstract

Objectives: To assess the quality of life among perimenopausal women distressing from abnormal uterine bleeding with identifying factors contributing to quality of life. Methods: A descriptive correlational study used three tools – structured interview questionnaire, pictorial blood loss assessment chart, and Short Form (SF36) questionnaire to a purposive sample of 300 women at perimenopause, distressing from abnormal uterine bleeding diagnosed in one of the hospitals in Pampanga, Philippines. Using SPSS v.20, the study applied frequency and percentage, mean and standard deviation, chi-square and probability of errors (p-value) with p ≤ 0.001, and ¬p ≤ 0.05 levels were considered statistically significant, and Pearson product moment correlation coefficient (R). Results: Most participants aged 45 to 50 (xÌ„=46.5, SD ± 2.83) years old, married (n=220, 73.3%), and living in urban areas (n=244, 81.3%). Majority experienced heavily soaked pad at their first two days (n=256, 85.3%) and moderately soaked pad at their tenth day (n=174, 58.0%) which led to physical difficulty in work performance (n=296, 98.7%) and limitations to other routine activities (n=300, 100%). A high statistically significant difference between the total quality of life and their marital status (p-value=0.00), and likewise statistically significant difference to level of education (p-value=0.12), and level of education (p-value=0.02) are greatly perceptible. Conclusion: The study revealed a moderate quality of life in women distressing from abnormal uterine bleeding with a negative correlation to menstrual flow. Self-care guidelines development to improve quality of life among perimenopausal women is exceptionally recommended.

Keywords

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding; Dysfunctional; Perimenopause; Quality of life

Introduction

Menopause is characterized by physical cessation of production of ovarian hormone and end of productivity with history of irregular menstrual cycle or absence of menstrual bleeding for more than three months leading to menorrhagia and abnormal uterine bleeding, and psychological changes. [1-3] Abnormal uterine bleeding or menorrhagia is resulting from hormonal disruption or imbalances without clear causes. [1,4-6] However, some studies relate the abnormal bleeding to organic and non-organic causes yet painless or asymptomatic bleeding to immaturity of hypothalamic pituitary-ovarian axis leading to hormonal disturbances with iron deficiency anemia as a more common complication. [4,5,7,8]

Quality of life is a multidimensional concept that includes different domains such as psychological, physical, spiritual, emotional and social well-being. It measures the individual ability to perception of one’s position in life and expectation of one’s goals in relation with value system and culture and degree of satisfactions. [9] Therefore, nursing plays an effective role in managing and providing effective interventions, and minimizing excessive bleeding episodes without further complications in women through encouraging to proper treatment and nutrition with improving quality of life and reduce morbidity rate. [10,11]

Abnormal uterine bleeding is considered a direct significant healthcare burden in women, their families, and society as a whole with up to 15% of gynecologists’ office visits in the Middle East. [12] More so, up to 95% of cases in adolescent group are considerably remarkable but 70% of all gynecologic visits by peri- and postmenopausal women. [13,14] Other studies, however, reported about 30% of all women had menorrhagia. [15] Recent studies reported 24% of women in Egypt suffer from abnormal uterine bleeding. [16] Extreme menstrual bleeding has numerous side effects, involving mainly iron deficiency anemia, reduced quality of life that a health problem needs more healthcare costs due to its key suggestion for recommendation to gynecological outpatient clinics. Menorrhagia is a hindering setback for several women and a main clinical confront for gynecologists. Half of women populace with menorrhagia has no organic trigger. Abnormal uterine bleeding is consequently a diagnosis of prohibiting with a substantial financial and qualityof- life burden. It marks women’s health together medically and socially. [8] It affects women’s quality of life that reflects on their occupational, physical, social, and emotional functioning. [17] It has been suggested that early intervention or management by healthcare providers may decrease or prevent negative impact on women’s quality of life.

However, there are limited studies that examine the quality of life among perimenopausal women suffering from abnormal uterine bleeding. Therefore, this descriptive correlational study is designed to assess perimenopausal women suffering from abnormal uterine bleeding and the contributing factors to it.

Aim

The study aimed to assess the quality of life of women at perimenopause distressing from abnormal uterine bleeding and its contributing factors. Precisely, it intends to (1) determine sociodemographic characteristics and menstrual history of participants; (2) identify participants’ blood loos according to soaked pads scoring and presence of clots; (3) determine participants’ total quality of life dimensions; (4) identify significant relationship between participants’ total quality of life and their sociodemographic characteristics, menstrual history, and duration of bleeding; and, (5) examine correlation between participants’ total quality of life and their blood loss specifically menstrual flow and presence of clots.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive correlational study was designed to assess perimenopausal women’s quality of life since distressing from abnormal uterine bleeding and its contributing factors. An ethical approval was obtained from the Nursing Director, Rafael Lazatin Memorial Medical Center (RLMMC) – a government healthcare facility that provides several free healthcare services that extend to include all patients seeking medical or healthcare assistance, and in accordance with the code of ethics in the Declaration of Helsinki. According to hospital statistics annual range by using Slovin’s formula, a purposive sample of 300 perimenopausal women were selected, aged between 40 to 50 years old, free from any medical or gynecological problem rather than already diagnosed in the outpatient and inpatient clinics of Obstetric and Gynecological Department of RLMMC with abnormal uterine bleeding for at least three months were included. However, women who had any medical condition that led to bleeding disorders, had blood disorder, and use any form of contraceptive methods that led to abnormal bleeding were excluded in the study.

Data collection instruments comprised of three tools – structured interview questionnaire, pictorial blood loss assessment chart, and SF-36 short form questionnaire. A twopart (sociodemographic characteristics and menstrual history assessment) nine-item structured interview questionnaire was developed in a literature-based approach and subsequently validated by experts in the field. Pictorial blood loss assessment charts was adopted as a guide to estimate days of bleeding and presence of clots during menstruation with scoring system is notified when menstrual blood loss is more than 80 ml per cycle or heavily soaked pads (20 points) and more than seven days bleeding duration, moderately soaked (5 points, and less than 5 ml or lightly soaked (1 point). [18] Presence of large clot is estimated with 5 ml, moderate clot in three ml, and small clot in one ml of blood loss. Finally, a Short Form (SF-36) questionnaire for health survey was likewise adopted to assess women’s quality of life and health status. [19] The questionnaire composed of questions related in assessing general health, mental health, vitality, activity, and sexual functions on 5-point Likert scale while physical role functions and religious activity on three-point Likert scale. A total score ranged from 0-100 is divided to three levels – high (>75%), moderate (50-75%), and low (<50%). All questionnaires were translated in native language, pilot tested to 10% (30 women), obtained validity and a strong internal consistency reliability score of 0.74.

An attached informed consent explicating the nature and target of the study to participate was provided in the questionnaire before distribution. More so, it was made clear that participation is of no harm but completely voluntary and can withdraw anytime without being penalized. All responses were preserved anonymously, maintained entirely confidential for research purposes use only.

Data analysis

Using SPSS v.20, frequency and percentage were used to organize, summarize and thus condensing numerical raw data. Mean and standard deviation, chi-square and probability of errors (p-value) with ¬ p ≤ 0.001 and ¬p ≤ 0.05 levels were considered statistically significant were applied to examine the relation between categorical variables. Pearson product moment correlation coefficient (R) was calculated to test relation between different numerical variables.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics and menstrual history of participants

Table 1 showed that most studied women aged 45 to 50 (x̄=46.5, SD ± 2.83) years old, married (n=220, 73.3%), went to intermediate education (n=140, 46.7%), living in urban area (n=244, 81.3%), and unemployed yet home-stay as housewife (n=152, 50.7%). Nearly half of them had menarche between 11- 15 years old (x̄=12.9, SD ± 1.17), in regular menstrual cycle (n=272, 90.7%), for five days in duration (n=168, 56.0%), and associated with pain (n=300, 100.0%) and ploating (n=190, 63.3%) during menses.

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | |||

| Age | 45-50 years old | 46.5 | 2.83 |

| n | % | ||

| Marital | |||

| Single | 28 | 9.3 | |

| Married | 220 | 73.3 | |

| Widow | 28 | 5.3 | |

| Divorced | 24 | 8.0 | |

| Education | |||

| Illiterate | 74 | 24.7 | |

| Basic | 68 | 22.7 | |

| Intermediate | 140 | 46.7 | |

| High | 18 | 6.0 | |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 244 | 81.3 | |

| Rural | 56 | 18.7 | |

| Occupation | |||

| Employed | 148 | 49.3 | |

| Unemployed | 152 | 50.7 | |

| Menstrual history | Mean | SD | |

| Range | |||

| Menarche age | 11-15 years | 12.9 | 1.17 |

| n | % | ||

| Regularity | |||

| Regular | 272 | 90.7 | |

| Irregular | 28 | 9.3 | |

| Associated symptoms | |||

| Pain | 300 | 100.0 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 144 | 48.0 | |

| Change in appetite | 144 | 48.0 | |

| Ploating | 190 | 63.3 | |

| Duration | |||

| 2 days | 10 | 3.3 | |

| 4 days | 6 | 2.0 | |

| 5 days | 168 | 56.0 | |

| 6 days | 62 | 20.7 | |

| 7 days | 54 | 18.0 | |

| Total | N=300 | 100.0 | |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics and menstrual history of participants.

Participants’ blood loss according to soaked pads scoring and presence of clots

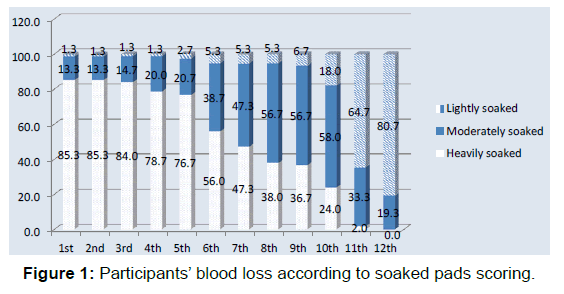

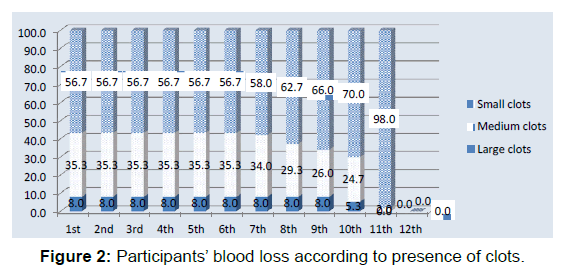

In Figure 1, it revealed that majority of studied women experienced heavily soaked pad at their first two days (n=256, 85.3%), moderately soaked pad at their tenth day (n=174, 58.0%), and lightly soaked at their 12th day (n=243, 80.7%). Furthermore, Figure 2 showed that minority of them had large clots at their first nine days (n=24, 8.0%) but later majority had small clots start at their 11th day (n=294, 98.0%).

Participants’ total quality of life dimensions

Table 2 illustrated the total quality of life dimensions of studied participants. Majority of studied women had physical limitations such as walking for more than a mile (n=250, 83.3%) and family caring (n=282, 94.0%), moderate activity (n=280, 93.3%), and difficulty in performing work with extra effort (n=296, 98.7%) but not all activities especially related to bathing or dressing (n=262, 87.3%). Mental depression or hopelessness (n=282, 94.0%); perceived less emotionally functioning (n=286, 95.3%); powerlessness and fatigue (n=300, 100%) with disturbed sleep at some time (n=182, 60.7%) were remarkably noticeable. However, studied women reported absence of bodily pain during the past four weeks (n=255, 85%) and if pain occurs, it is perceived as not interfering ones’ work (n=268, 89.3%) but physical health, in general, interferes ones’ normal social activities (n=180, 60.0%). A perceived worse expected general health (n=146, 48.7%) was likewise observed. Furthermore, studied married women perceived their sexual health as having loss of sexual desire (n=138, 62.7%), lack of lubrication (n=136, 61.7%) with decrease sexual response at some time (n=108, 49.1%), and a decrease sexual response (n=108, 49.1%). More so, all studied women experienced limitations to routine activities (n=300, 100.0%).

| Total quality of life dimensions | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical role limitation | Limited a lot | Limited a little | Not limited at all | |||||||||

| 1. | Vigorous activitiessuch as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports | 154 | (51.3%) | 146 | (48.7%) | 0 | (0%) | |||||

| 2. | Moderate activities,such as moving table, push a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf | 20 | (6.7%) | 280 | (93.3%) | 0 | (0%) | |||||

| 3. | Shooping | 36 | (12.0%) | 258 | (86%) | 6 | (2%) | |||||

| 4. | Climbing several flights of stairs | 140 | (46.7%) | 152 | (50.7%) | 8 | (2.7%) | |||||

| 5. | Bending, kneeling, or stooping | 14 | (4.7%) | 126 | (42%) | 160 | (53.3%) | |||||

| 6. | Walking more than mile | 250 | (83.3%) | 44 | (14.7%) | 6 | (2%) | |||||

| 7. | Bathing or dressing yourself | 20 | (6.7%) | 18 | (6%) | 262 | (87.3%) | |||||

| 8. | Doing any work outside the house | 236 | (78.7%) | 60 | (20%) | 4 | (1.3%) | |||||

| 9. | Caring of family member | 18 | (6%) | 282 | (94%) | 0 | (0%) | |||||

| Physical functions | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| 1. | Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities | 14 | (4.7%) | 286 | (95.3%) | |||||||

| 2. | Were limited in the kind of work or other activities | 10 | (3.3%) | 290 | (96.7%) | |||||||

| 3. | Had difficulty performing the work or other activity( it took extra effort) | 4 | (1.3%) | 296 | (98.7%) | |||||||

| Mental health | None of the time | Sometimes | All the time | |||||||||

| 1. | Have you been a very nervous person | 0 | (0%) | 220 | (73.3%) | 80 | (26.7%) | |||||

| 2. | Have you feeling depressed or hopelessness | 4 | (1.3%) | 282 | (94%) | 14 | (4.7%) | |||||

| 3. | Have you felt unable to concentrate | 12 | (4%) | 226 | (75.3%) | 62 | (20.7%) | |||||

| 4. | Have you feeling unhappy person | 26 | (8.7%) | 226 | (75.3%) | 48 | (16%) | |||||

| 5. | Have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up | 94 | (31.3%) | 186 | (62%) | 20 | (6.7%) | |||||

| Emotional role function | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| 1. | Accomplished less than you would like | 14 | (4.7%) | 286 | (95.3%) | |||||||

| 2. | Didn’t do work or other activities as carefully as usual | 18 | (6%) | 282 | (94%) | |||||||

| Vitality and fatigue | None of the time | A little of the time | Some of the time | Most of the time | All of the time | |||||||

| 1. | Feeling tired | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 100 (33.3%) | 162 (54%) | 38 (12.7%) | ||||||

| 2. | Feeling very sick | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 128 (42.7%) | 166 (55.3%) | 6 (2%) | ||||||

| 3. | Feeling that you have a lot of energy | 270 (90%) | 10 (3.3%) | 12 (4%) | 8 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| 4. | Feeling that you have a lot of power and activity | 300 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| 5. | Feeling that you are unable to sleep | 20 (6.7%) | 6 (2%) | 182 (60.7%) | 86 (28.7%) | 6 (2%) | ||||||

| Bodily pain | Extremely | Severe | Moderately | A little bit | Not at all | |||||||

| 1. | How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks? | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.3%) | 40 (13.3%) | 256 (85.3%) | ||||||

| 2. | How much did pain interfere with your normal work including both work outside the home and housework? | 0 0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (10.7%) | 268 (89.3%) | ||||||

| Social activity | Extremely | Quite of time | Some of the time | slightly | Not at all | |||||||

| 1. | How much of time have your physical health interfered with your social activities? | 0 (0%) | 41 (14%) | 180 (60%) | 72 (24%) | 6 (2%) | ||||||

| General health | Definitely false | Mostly false | Don’t now | Mostly true | Definitely true | |||||||

| 1. | I seem to get sick a little easier than other people | 152 (50.7%) | 12 (4%) | 68 (22.7%) | 10 (3.3%) | 58 (19.3%) | ||||||

| 2. | I am as healthy as anybody I know | 146 (48%) | 114 (38%) | 36 (12%) | 4 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| 3. | I expect my health to get worse | 14 (4.7%) | 18 (6%) | 66 (22%) | 146 (48.7%) | 56 (18.7%) | ||||||

| 4. | My health is excellent | 282 (94%) | 10 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.7% | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| Sexual function | None | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Usually | |||||||

| 1. | Dyspareunia | 18 (8.2%) | 0 (0%) | 102 (46.4%) | 8 (3.6%) | 92 (41.8%) | ||||||

| 2. | Loss of sexual desire or libido | 6 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 40 (18.2%) | 36 (16.4%) | 138 (62.7%) | ||||||

| 3. | Decrease in Frequencyof intercourse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 40 (18.2%) | 58 (26.4%) | 122 (55.5%) | ||||||

| 4. | Decrease in sexual response | 6 (2.7%) | 8 (3.6%) | 108 (49.1%) | 38 (17.3%) | 60 (27.3%) | ||||||

| 5. | Lack of lubrication | 0 (0%) | 20 (9.1%) | 30 (13.6%) | 34 (15.5%) | 136 (61.7%) | ||||||

| Routine activity | Not limited at all | Limited a little | Limited a lot | |||||||||

| 1. | From self-caring | 0 | (0%) | 4 | (1.3%) | 296 | (98.7%) | |||||

| 2. | From young family member rearing | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 300 | (100%) | |||||

| 3. | From housekeeping | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 300 | (100%) | |||||

Table 2: Participants’ total quality of life dimensions.

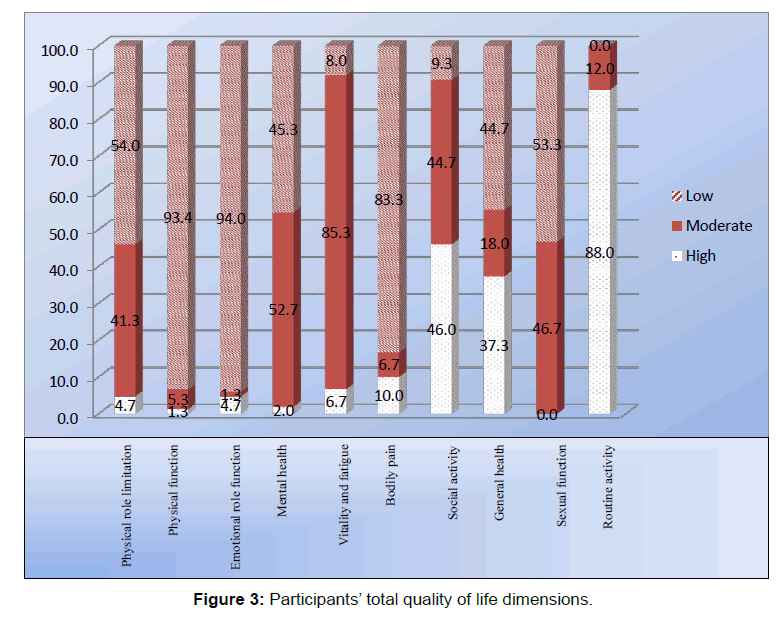

Figure 3 demonstrated the frequency distribution of studied women’s total quality of life dimensions. A low quality of life is perceived in physical (n=280, 93.4%) and emotional role (n=282, 94.0%) functions. However, their routine activities (n=264, 88.0%) were perceived the cause of a high quality of life.

Significant relationship between participants’ total quality of life and their sociodemographic characteristics, menstrual history, and duration of bleeding

Table 3 displayed that the participants’ total quality of life is highly statistically significant to marital status (p-value=0.000) and menstrual cycle (p-value=0.001). Furthermore, residence (p-value=0.02), level of education (p-value=0.012), and menstrual duration (p-value=0.029) were likewise statistically significant. However, no statistically significant relationship is distinguished in their age and occupation.

| Total quality of life | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Mean ± SD | x2 | p-value | ||

| Age | 46.5 ± 2.83 | 6.23 | 0.18 | ||

| Marital | 51.7 | 0.000** | |||

| Education | 16.3 | 0.012* | |||

| Residence | 7.58 | 0.02* | |||

| Occupation | 5.24 | 0.07 | |||

| Menstrual history and duration | Low (n=120) | Moderate (n=162) | High (n=18) | ||

| Regularity | |||||

| Regular | 96 (80%) | 158 (97.5%) | 18 (100%) | 13.5 | 0.001** |

| Irregular | 24 (20%) | 4 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Duration | |||||

| 2 days | 0 (0%) | 10 (6.2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 4 days | 0 (0%) | 6 (3.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 5 days | 62 (51.7%) | 88 (54.3%) | 18 (100%) | 17.1 | 0.029* |

| 6 days | 26 (21.7%) | 36 (22.2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 7 days | 32 (26.7%) | 22 (13.65) | 0 (0%) | ||

*statistically significant at p < 0.05

**highly statistically significant at p < 0.001

Table 3: Significant relationships between participants’ total quality of life and their sociodemographic characteristics, menstrual history, and duration of bleeding.

Correlation between participants’ total quality of life and their blood loss specifically menstrual flow and presence of clots

Table 4 illustrated that the more menstrual flow is experienced, the more perceived decrease quality of life is reported. Therefore, a negative correlation is seen between participants’ total quality of life and their menstrual flow and clots (r=-0.07).

| Total quality of life | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood loss | R | p-value | |

| Menstrual flow | -0.07 | 0.37 | |

| Clots | 0.05 | 0.50 | |

*statistically significant at p < 0.05

**highly statistically significant at p < 0.001

Table 4: Correlation between participants’ total quality of lie and their blood loss specifically menstrual flow and presence of clots.

Discussion

Abnormal uterine bleeding affects the physical condition of a woman, as well as the psychological aspect on the quality of life; without structural abnormalities detected but having an abnormal uterine bleeding due to hormonal mechanism that may relate to uncomfortable physical, emotional, sexual and even professional aspect which impairs the quality of life of a woman. [13,20-22]

While abnormal uterine bleeding was common to women aged 41 to 50 years, married, and as housewife. [2,21,23] However, a study indicates that 18 to 25 years of age has the highest number of respondents affected with abnormal uterine bleeding, while the lowest percentage belongs to 55-year-old women, mostly residing in urban areas, and regrettably unable to obtain their education. [5,21,23]

Most women’s menstrual history had menarche at 12 years old and those associated symptoms with regular periods of five days. [24,25] Due to major disease factor of abnormal uterine bleeding, the most reason for women is excessive menstrual blood loss. [21] While other studies, thirty-two percent experiences heavy menstrual flow during first two days, thirty-nine percent have moderate menstrual bleeding, and 15% with light menstrual blood flow. [26] Formation of blood clots during menstruation is unusual to perimenopausal women but this may happen while having excessive bleeding due to presence of uterine tissue during shedding of the endometrial tissue. [27]

More than half women had decreased in work performance; and most women felt that heavy menstruation affects their performance on sports and vigorous activities, and family caring with majority has less accomplishments. [5,23,28] Some studies found that women felt less energy and no physical strength and has difficulty of falling sleep. [28,29] Loss of sexual desire and lack of lubrication are likewise remarkably noticeable with vaginal dryness and less libido. [23]

Various studies reveal low point on the total quality of life of women to physical work limitation, moderate quality of life in vitality and fatigue, and emotional function. [23,30,31]

Total quality of life measures all life’s domains and can be affected in relation to physical role limitation and social responsibility. [5,28] An individual perception to quality of life is based on the situation, standards, expectations and cultural values and system. [32] In this study, the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics affect respondents’ total quality of life. Studies state that a higher proportion of urban women have been reported to be affected in their quality of life such as the physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environmental domains compared to the rural women. [33,34] Contrarily, one study indicates the difference in culture, customs and character of rural communities and perimenopausal women background who lived in rural areas are more affected in their quality of life. [35] In addition, marital status has significant relationship to total quality of life in which current findings is congruent to a study that identifies married multiparous women were considered to be the most affected from abnormal uterine bleeding. [23] This is associated with hormonal changes; more average blood loss and parity doubtlessly augments the frequency of irregular bleeding. Authors have implied that higher occurrence in married women can be elucidated on the basis of general clinical population which illustrates advanced frequency of married women. Furthermore, majority of the participants in the current study demonstrated a normal cycle of five days. Previous studies reveal that mostly women regardless of regular cycle had experienced abnormal uterine bleeding. [25,36] This was linked with hormonal imbalances which may precipitate increase in quantity of blood loss and presence of blood clots which influences women to develop any form of abnormal uterine bleeding. Moreover, some studies state that variates in menstruation consequential from augmented quantity, extent, or incidence may influence physical, emotional sexual and professional characteristics of women’s lives, impairing their quality of life. [22] Yet, current study indicated that menstrual duration revealed a significant relationship to total quality of life. Studies confirmed that any abnormal uterine bleeding can be a source of anxiety distressing quality of life, reporting the major impact menstruation to physical conditions affecting daily performance while bleeding pattern commonly disrupts daily life. [4,23,37]

The current study showed negative correlation between respondents’ total quality of life and menstrual history (duration of menstrual bleeding and presence of clots). The relation between menstrual history with more increase in duration of bleeding and presence of blood clots decreases the total quality of life. Likewise, a certain study identifies heavy menstrual bleeding which significantly affects quality of life at Karolinska University and found that there was negative relation between duration of period, presence of clots and total quality of life. [26] A few studies investigate menstrual flow that can affect women the most in which women with self-reported heavy menstrual bleeding pointed to pain, heaviness, mood change/tiredness and irregularity, and that abnormal uterine bleeding indicates irritation/inconvenience, bleeding-associated pain, selfconsciousness about odor, social embarrassment, and ritualistic behavior affects the daily life activities of respondents. [38,39]

These findings were also consistent with the response to a study considering discernments and behavior accompanying with menstrual bleeding. [26] In another study, 80% of women with heaviest menstrual flow days impacted attendance and performance at work and/or school, performance and the usual housekeeping tasks. [5]

Limitation

By means of a random sampling in a larger population is approvingly advocated to prevent restriction to generalize findings.

Conclusion

Abnormal uterine bleeding is one of the most common causes of perimenopausal disturbance, affecting not only physical condition but likewise extent to involve psychological aspect in women’s quality of life. In the study, more than half of studied women suffering from abnormal uterine bleeding perceived a quality of life in moderation. However, it was identified negatively correlated with menstrual flow.

Recommendations

Development of self-care guideline is highly suggested to recuperate the quality of life among perimenopausal women who are suffering from abnormal uterine bleeding. Likewise, the use booklet and posters as a method to increase women awareness regarding normal and abnormal blood loss amount and duration in outpatient clinics is compellingly recommended. A large sample of perimenopausal women diagnosed with abnormal uterine bleeding in different outpatient clinics or health center is similarly suggested for future research.

Acknowledgement

The authors are gratified to women that voluntarily participated in the implementation of this scholarly academic work.

Authors’ Contributions

EEF and AMS conceptualized, designed, and data acquisition of the study. EEF, AMS, and CDA analyzed data statistically and prepared the draft manuscript. All authors equally provided definition of intellectual content, literature search, and data analysis. Likewise, all authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft with the acknowledgement that all authors made substantial contributions to the work reported in the study until publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Dodd N, Sinert R. Abnormal vs. dysfunctional uterine bleeding: A guide to women's health. Harv Health Pub. 2019; 49: 11-14.

- Goldstein SR, Lumsden MA. Abnormal uterine bleeding in perimenopause. Climacteric. 2017; 20: 414-420.

- Al-Dughaither A, Al-Mutairy H, Al-Ateeq M. Menopausal symptoms and quality of life among Saudi women visiting primary care clinics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Womens Health. 2015; 7: 645-653.

- Motta T, Langana AS, Vitale SG. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding: Good practice in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2018; 99-115.

- Mohamed AHG. Abnormal uterine bleeding and its impact on women life. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2017; 6: 30-37.

- Speroff L, Fritz M. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding: Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 7th ed. Baltimore MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017; 547-571.

- Elmaogullari S, Aycan Z. Abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2018; 10: 191-197.

- Sriprasert I, Pakrashi T, Kimble T, Archer D. Heavy menstrual bleeding diagnosis and medical management. Contracept Reprod Med. 2017; 2: 1-8.

- Carulla LS, Lucas R, Mateos JLA, Miret M. Use of the terms “well-being” and “quality of life” in health sciences: A conceptual framework. Eur J Psychiat. 2014; 28: 55-70.

- Ayers D, Lappin J, Liptok L. Abnormal vs. dysfunctional uterine bleeding: What’s the difference? Nursing 2020. Sup: A guide to women’s health. 2004; 11: 11-14.

- Abbott JA. Adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-A)-pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract. Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017; 40: 68-81.

- Nelson AL, Ritchie JJ. Severe anemia from heavy menstrual bleeding requires heightened attention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 213: 97.

- Motta T, Lagana AS, Valenti G, LA Rosa VL, Noventa M, Vitagliano A. et al. Differential diagnosis and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescence. Minerva Ginecol. 2017; 69: 618-630.

- Deligeoroglou E, Karountzos V, Creatsas G. Abnormal uterine bleeding and dysfunctional uterine bleeding in pediatric & adolescent gynecology. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013; 29: 74-78.

- Davis E, Sparzak PB. Abnormal uterine bleeding (Dysfunctional uterine bleeding). Treasure Island: Stat Pearls Publishing; 2019.

- Aboushady RMN, El-Saidy TMK. Effect of home-based stretching exercises and menstrual care on primary dysmenorrhea and premenstrual symptoms among adolescent girls. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2016; 5: 47-57.

- Poomalar GK, Arounassalame B. The quality of life during and after menopause among rural women. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013; 7: 135-139.

- Zakherah MS, Sayed GH, El-Nashar SA, Shaaban MM. Pictorial blood loss assessment chart in the evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding: Diagnostic accuracy compared to alkaline hematin. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011; 71: 281-284.

- Bourdel N, Chauvet P, Billone V, Douridas G, Fauconnier A, Gerbaud L. et al. Systematic review of quality of life measures in patients with endometriosis. PLoS One. 2019; 14: 1-32.

- Talukdar B, Mahela S. Abnormal uterine bleeding in perimenopausal women: Correlation with sonographic findings and histopathological examination of hysterectomy specimens. J Midlife Health. 2016; 7: 73-77.

- Dhanalakshmi S, Abinaya S, Kailash A. Quality of life in dysfunction uterine bleeding women. Research J Pharm. and Tech. 2016; 9: 1091-1096.

- Pinto CLB, Silva ACJ, Yela DA, Soares JM. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017; 39: 358-368.

- Nayak AK, Hazra K, Jain MK. Clinico-pathological evaluation of dysfunctional uterine bleeding among perimenopausal women. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2017; 4: 77-83.

- Karout N, Hawai SM, Altuwaijri S. Prevalence and pattern of menstrual disorders among Lebanese nursing students. East Mediterr Health J. 2012; 18: 346-352.

- Rafique N, Al-Sheikh MH. Prevalence of menstrual problems and their association with psychological stress in young female students studying health sciences. Saudi Med J. 2018; 39: 67-73.

- Karlsson TS, Marions LB, Edlund MG. Heavy menstruation bleeding significantly affects quality of life. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014; 93: 52-57.

- Davies J, Kadir RA. Heavy menstrual bleeding: An update on management. Thromb Res. 2017; 151: 70-77.

- Jayabharathi B, Judie A. Severity of menopausal symptoms and its relationship with quality of life in post-menopausal women: A community-based study. Int J Pharma Clin Research. 2016; 8: 33-38.

- Elazim H, Lamadah SM, Al Zamil L. Quality of life among of menopausal women in Saudi Arabia. Jordan Med J. 2014; 48: 227-242.

- Bhatiyani B, Dhumale S, Pandeeswari B. Knowledge, attitude and behaviour of women towards abnormal menstrual bleeding and its impact on quality of life. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 6: 4291-4296

- Kadir RA, Edlund M, Von Mackensen S. The impact of menstrual disorders on quality of life in women with inherited bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2010; 16: 832-839.

- Gokyildiz S, Aslan E, Beji NK, Mecdi M. The effect of menorrhagia on women’s quality of life: A case-control study. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 2013: 1-7.

- Sharma S, Mahajan N. Menopausal symptoms and its effect on quality of life in urban versus rural women: A cross-sectional study. J Midlife Health. 2015; 6: 16-20.

- Yohanis M, Tiro E, Irianta T. Women in the rural areas experience more severe menopause symptoms. Indones J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 37: 86-91.

- Martinez JA, Palacios S, Chavida F, Perez M. Urban-rural differences in Spanish menopausal women. Rural Remote Health. 2013; 13: 1865.

- Busari O. Menstrual knowledge and health care behavior among adolescent girls in rural, Nigeria. Int J Appl Sci Tech. 2012; 2: 149-154.

- Khamdan HY, Aldallal KM, Almoosa EM, AlOmani NJ, Haider ASM, Abbas ZI, et al. The impact of menstrual period on physical condition, academic performance and habits of medical students. J Women’s Health Care 2014; 3: 1-4.

- Santer M, Wyke S, Warner P. What aspects of periods are most bothersome for women reporting heavy menstrual bleeding? Community survey and qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 2007; 7: 1-6

- Matteson KA, Boardman LA, Munro MG, Clark MA. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a review of patient-based outcome measures. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92: 205-216.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.