Possible Hematological Changes Associated with Acute Gastroenteritis among Kindergarten Children in Gaza

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Nahed Ali Al Laham

Department of Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Al‑Azhar University, P.O. Box 1277, Gaza, Palestine

E-mail: n.lahamm@alazhar.edu.ps

Citation: Al Laham NA, Elyazji MS, Al-Haddad RJ, Ridwan FN. Possible hematological changes associated with acute gastroenteritis among Kindergarten children in Gaza. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2015;5:292-8.

Abstract

Background: Gastroenteritis is considered one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in children especially in developing countries. It is a major childhood problem in Gaza and one of the most common etiologic agents of iron deficiency anemia (IDA). Aim: This study was conducted to investigate possible changes in blood parameters that are associated with gastroenteritis infection among kindergarten children in Gaza. Subjects and Methods: A cross‑sectional case–control study was performed including kindergarten children suffering from gastroenteritis and matched healthy control group. Types of etiological agents were identified using standard microbiological and serological procedures. Blood samples were collected for estimation of complete blood count and for determination of serum iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), and transferrin saturation. Independent sample t‑test was used for comparisons and performed using SPSS software version 17(Chicago Illinois USA). Results: The prevalence of enteric pathogens among cases (88.5% [85/96]) was significantly higher than in asymptomatic controls (11.1% [6/54]). The most common enteric pathogens isolated were Entamoeba histolytica (28% [42/91]) and Giardia lamblia (26.7% [40/91]). Blood tests revealed that 21.8% (21/96) of cases and 14.8% (8/54) of controls had IDA, which were not significantly different. Meanwhile, a significant difference was found between the TIBC and hemoglobin in cases compared to controls. Conclusion: This study indicates that gastroenteritis infection could be considered as a common health problem in kindergarten children in Gaza, and it is possibly associated with changes in hemoglobin concentration and TIBC.

Keywords

Acute gastroenteritis, Gaza, hematological changes, Iron deficiency, Kindergarten

Introduction

Worldwide, diarrheal diseases are continued to be a common health problem that increase the financial burden on the health systems particularly in developing countries. Acute gastroenteritis is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in children < 5‑years,[1‑3] especially in developing countries.[4‑7] Gastroenteritis is a serious burden to public health. Its etiologic agents include a wide variety of bacteria, viruses, and parasites.[8‑10] Serious outcomes are associated with these intestinal pathogens include malnutrition, impaired physical development, and reduced school achievement in children.[11] In Gaza, acute gastroenteritis is a common infection among children, associated with high morbidity and mortality rates when left without a proper treatment.[12]

Anemia is a major public health problem in both developed and developing countries that needs a national and international interventions to correct it and its underlying causes.[13,14] It is currently estimated that anemia affects about one‑quarter of the world’s population and estimated that 36% of developing world’s population suffers from this health condition.[13‑16]

Iron deficiency is recognized as the primary cause of anemia worldwide and is the most prevalent form of micronutrient malnutrition in the world. The etiology of anemia is multifactorial including nutritional habits, the bioavailability of micronutrients, parasitic infections, inflammation, and genetic factors;[15‑18] however, non‑nutritional causes of anemia are numerous and diverse. In the developing countries, common parasitic infections associated with blood loss can result in iron depletion, iron deficiency, and ultimately anemia.[19‑23] The negative effects of some protozoan and helminthes parasites on the absorption of some micronutrients leading to nutritional anemia have been reported in different scientific works.[18,24]

Gaza Strip (geographic coordinates 31°252 N, 34° 202 E) is a narrow region (365 km2) of land along the Mediterranean coast, just 41 km long and 6–12 km wide. It is one of the most heavily populated areas (4383 persons/km2) of the world with a total population about 1.7 million people.[25] In the present work, a prospective cross‑sectional case–control study was conducted in Gaza city to determine the type and prevalence of enteropathogens causing acute gastroenteritis among kindergarten children and to assess their possible effect on blood parameters and body iron status.

Subjects and Methods

Study population and sample collection

This study is a cross‑sectional case–control study conducted in Gaza from 1st of January to the 30th of June 2011. Sample selection was randomly done for 15 kindergarten in Gaza but covering all different localities and population clusters in Gaza. Sample size was determined using Sample Size Calculator according to the number of enrolled children in Gaza kindergartens (http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm) to define the enteropathogens causing gastroenteritis among kindergarten children and to find out their possible effect on blood parameters.

One hundred and ninety written requests were sent to the parents or guardians of the symptomatic cases and asymptomatic carriage (apparently healthy controls) in 15 kindergartens to have their approval to involve their child in the study. Thankfully, 96 of 115 (response rate 83.5%) and 54 of 75 (response rate 72.0%) of symptomatic cases and asymptomatic carriage, respectively, agreed to participate in the study and to provide stool and blood samples for further investigations. The 15 kindergartens are in geographically different localities and population clusters in Gaza.

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of our biology department and performed in accordance with the ethical standards established in the 1964 and 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and the modifications thereafter. All ethical considerations were followed including respect for the privacy of the subject. A signed consent form was obtained from the parents or guardians providing their acceptance and full understanding of this study and its aims. Stool samples were collected from cases and controls in clean, dry plastic containers in their kindergarten by the help and under the supervision of the investigator. They were tested using standard microbiological procedures according to the guidelines of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).[26] Furthermore, blood samples were collected on the same time by expert laboratory technologist for estimation of complete blood count (CBC) and serum samples were tested for determination of iron concentration and total iron binding capacity (TIBC).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All samples were collected from different kindergarten regions representing all parts of Gaza. Any child who is suffering from any chronic disease or was hospitalized was excluded. Children with gastroenteritis symptoms including watery, nonbloody or bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting or low‑grade fever considered as cases and apparently healthy matched controls (asymptomatic) were included.

Microbiological methods

Standard microbiological procedures and guidelines, as described by CLSI[26], were used. For the identification of parasites, fresh stool specimens prepared with saline and/or iodine were directly examined. In addition, flotation and sedimentation techniques were performed on all samples that gave negative result using direct microscopic examination. For detection of bacterial agents, fresh stool samples were plated directly or after enrichment step onto Salmonella‑Shigella, Hecktoen enteric, and Sorbitol MacConkey agars (HiMedia, India) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Suspected colonies were identified by standard laboratory procedures. For detection of viral agents, enzyme immunoassay (GastroVir‑Stripcolor kit) was used for the detection of Group A Rotavirus and Adenovirus serotype 40 and 41 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cori BioConcept, Belgium).

Complete blood count

About 2½ ml of venous blood were drown into sterile ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes, mixed and processed within 1 h by (Sysmex‑Kx‑21). The following parameters were calculated: White blood cells (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), platelets (PLT), hemoglobin, hematocrit (HCT), mean cell volume (MCV), mean cell hemoglobin (MCH), and MCH concentration (MCHC). Serum iron (SI) and TIBC were performed using Mindray Bs‑200, chemistry analyzer (Shenzhen Mindray Bio‑Medical Electronics, Shenzhen, China) on samples with hemoglobin concentration <11 g/dL.

Evaluation of iron deficiency anemia

In the present research, and due to the inadequate financial and laboratory resources, as well as the politically constrictive environment in the Gaza Strip, which negatively affects the availability of medical, laboratory equipment, chemicals and diagnostic kits to perform laboratory investigations, iron deficiency anemia (IDA) were considered in the kindergarten children; when transferrin saturation (SI/TIBC) was < 16% [27] in combination with low hemoglobin concentration < 11 g/dL for ≤ 4‑year‑old children, and < 11.5 g/dL for 5‑year‑old children.[28]

Determination of serum iron

Serum iron was determined by the colorimetric method according to the manufacturer instructions of DiaSys, Diagnostic Systems GmbH, Germany kit by using computerized chemical chemistry auto analyzer equipment (Mindray BS‑200).

Determination of total iron binding capacity

Total iron binding capacity was determined by the colorimetric method according to the manufacturer instructions of Linear Chemicals, Spain kit by using computerized chemical chemistry auto analyzer equipment (Mindray BS‑200).

Calculation of transferrin saturation

Transferrin saturation was calculated as a percentage of the ratio of SI to total TIBC.

Data analysis

The results that obtained from laboratory investigations were tabulated, encoded and statistically analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) program version 17 (Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive analysis and independent t‑test were performed. The differences were considered statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

General characteristics of the study population

The present study is a prospective cross‑sectional case–control study included 150 kindergarten children from Gaza city. The stool and blood samples were collected from children of both genders (56% [84/150] males and 44% [66/150] females). The ages of children enrolled in this study were 3 (8% [12/150]), 4 (34% [51/150]), and 5‑years (58% [87/150]). According to the study protocol, 96 diarrheal stool samples were collected from 51 boys (53.1% [51/96]), and 45 girls (46.9% [45/96]) and they considered as symptomatic cases. The asymptomatic carriage (controls group) included 33 boys (61.1% [33/54]) and 21 (38.9% [21/54]) girls.

Prevalence and type of enteropathogens isolated from cases and controls

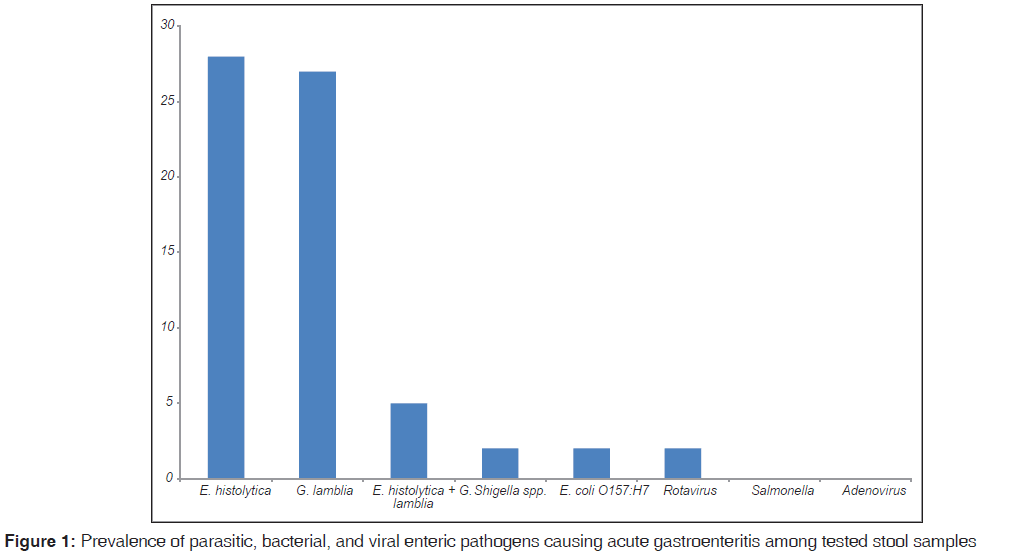

Overall, there were 91 samples (60.7% [91/150]) positive for parasitic, bacterial, and/or viral enteric pathogens. The parasitic etiologic agents had the highest prevalence rate (54.7% [82/150]) in comparison to the bacterial (4% [6/150]) and viral (2% [3/150]) etiologic agents. More than half of samples collected were positive for one or more parasitic agent. The highest isolated enteric pathogen was Entamoeba histolytica (28% [42/91]), followed by Giardia lamblia (26.7% [40/91]). Adenovirus and Salmonella were not isolated from all tested samples [Figure 1]. The overall prevalence of positive stools from symptomatic cases was significantly higher (88.5% [85/96]) than that isolated from asymptomatic controls (11.1% [6/54]).

Hematological parameters of cases and controls

Table 1 shows the CBC parameters of blood samples that collected from all enrolled children in this study. There was no significant differences between the mean score results of blood parameters tested for both, cases (diarrheal) and controls (nondiarrheal), except for the WBC which was significantly higher in cases (symptomatic) compared to control group (asymptomatic) (P < 0.01). However, the mean score result of hemoglobin concentration is slightly lower in cases compared to controls, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.32). The other blood parameters (RBC, HCT, MCV, MCHC, and PLT) had almost the same mean score results.

| Blood parameter | Presence of diarrheal | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrheal samples | Non-diarrheal samples | ||||

| Mean (SD) (n=96) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) (n=54) | 95% CI | ||

| RBC (×1012/L) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.5-4.6 | 4.6 (0.4) | 4.5-4.7 | 0.39 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.5 (0.9) | 11.3-11.7 | 11.6(0.8) | 11.4-11.9 | 0.32 |

| HCT (%) | 35.3 (2.3) | 34.8-35.7 | 35.8(2.2) | 35.2-36.4 | 0.18 |

| MCV (fl) | 78.1 (4.1) | 77.2-78.9 | 78.5(5.7) | 76.9-80.0 | 0.6 |

| MCH (pg) | 25.4 (1.8) | 25.1-25.8 | 25.5(2.3) | 24.9-26.1 | 0.8 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 32.5 (1) | 32.3-32.7 | 32.5(1.1) | 32.2-32.8 | 0.64 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 388.5 (99) | 368.4-408.6 | 385.4(92.4) | 360.2-410.7 | 0.85 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 9.7 (3.2) | 9.0-10.3 | 8.3 (2.7) | 7.6-9.0 | <0.01* |

Table 1: Differences in blood parameters among cases (diarrheal) and controls (no diarrheal)

Serum iron, TIBC, and transferrin saturation level were performed only on blood samples that have hemoglobin concentration < 11 g/dL. SI level divided by the TIBC multiplied by 100 gives a transferrin saturation level. There were 21 (21.9% [21/96]) and 8 (14.8% [8/54]) children from the cases (diarrheal samples) and controls (no diarrhea) showing IDA with hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL.[27‑29] Decreased hemoglobin, SI, and transferrin saturation levels were found in cases compared to controls, but this difference was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the results showed a statistically significant difference between the level of TIBC of cases compared to controls (P < 0.01) [Table 2].

| Blood parameter | Presence of diarrheal among anemic children | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrheal samples | Non-diarrheal samples | |||||

| Mean (SD) (n=21) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) (n=80) | 95% CI | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.3 (0.6) | 10.2-11.6 | 10.4 (0.6) | 11.5-11.8 | 0.71 | |

| SI (µg/dL) | 34.4 (10.5) | 29.6-39.2 | 40.3 (2.4) | 19.5-61.0 | 0.38 | |

| TIBC (µg/dL) | 316.6 (23.6) | 306.9-328.4 | 363.7 (57) | 317.6-413.1 | <0.01* | |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 11.0 (3.8) | 9.3-12.7 | 11.4 (7.2) | 5.4-17.4 | 0.84 | |

Table 2: Hemoglobin, SI, TIBC, and transferrin saturation results of cases and controls having hemoglobin concentration <11 g/dL

Possible effect of parasitic infection on blood parameters

The mean level of blood parameters tested from children with different parasitic infections showed almost the same values irrespective of the type of parasite or even when double infection with two parasites were existed. Furthermore, comparing these results with the blood parameters values tested from children with negative parasitic samples revealed no clear differences. Yet, the mean value of WBC was found to be higher in blood samples of children with E. histolytica infections compared to blood samples of children with G. lamblia infection alone or children without any parasitic infection [Table 3]. These differences were statistically significant.

| Blood parameter | NegativeMean (SD) (n=61) | G. lambliaMean (SD) (n=40) | E. histolyticaMean (SD) (n=42) | E. histolytica and G. lambliaMean (SD) (n=7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC (×1012/L) | 4.6 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.4 (0.3) | 4.7 (0.2) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.6(0.9) | 11.6 (.8) | 11.4(1.0) | 12.0 (0.6) |

| HCT (%) | 35.7(2.3) | 35.3(2.1) | 35.2(2.5) | 36.1 (1.7) |

| MCV (fl) | 78.1(5.4) | 79.1(3.5) | 77.7(5.0) | 77.6 (2.2) |

| MCH (pg) | 25.2(2.4) | 25.9(1.4) | 25.2(2.2) | 25.9 (0.2) |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 32.3(1.1) | 32.7(0.9) | 32.5(1.1) | 33.3 (0.7) |

| PLT (×109/L) | 385.5(95.3) | 390.2 (102.3) | 379.9(90.3) | 432.7 (114.6) |

| WBC (×109/L) | 8.7 (3.1) | 8.8 (2.3) | 10.0 (3.4)* | 10.6 (2.6)* |

| SI (µg/dL) | 37.3 (22.8) | 36.9 (14.4) | 34.3(7.4) | ND |

| TIBC (µg/dL) | 358.5(53.2) | 311.4(20.8) | 319.8(25.9) | ND |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 10.7(6.5) | 12.0(5.1) | 10.9(2.8) | ND |

Table 3: Mean values of blood parameters in association with different parasitic pathogens

Discussion

Gastrointestinal diseases are a major public health problem for children in Gaza Strip, as in other developing communities around the world, and are among the most common causes of IDA due to gastrointestinal tract blood loss.[20,30] Gastroenteritis can also be accompanied by malnutrition with reduced iron intake further contributing to the IDA.[19,20,22,23] Many previous and most recent studies from Gaza Strip and other parts of Palestine (West Bank) revealed a significant prevalence of IDA among kindergarten, pre‑ and age‑school children due to gastrointestinal infection and other nutritional factors.[31‑38]

In this study, CBC, SI, and TIBC were performed to investigate the possible effect of gastrointestinal infections on these blood parameters among kindergarten children suffering from community gastroenteritis and their comparable healthy controls. The findings of our study showed that 21.8% (21/96) of the diarrheal cases also had iron deficiency with hemoglobin concentration < 11 g/dL, compared to only 14.8% (8/54) of non‑diarrheal controls. The hemoglobin level with other blood parameters was slightly lower in diarrheal cases than in non‑diarrheal controls. In the iron deficient children, SI, TIBC, and transferrin saturation were also slightly lower in diarrheal cases. Assuming no interference from other etiological factors like inflammation, the results suggest that IDA is increased in diarrheal cases, although this difference did not achieve statistical significance.

This could be due to the fact that the infection was not chronic enough to cause malabsorption or sufficient blood loss to effect iron levels. The results of this work are inconsistent with those noted in other studies, where the authors found that the high prevalence of enteropathogens was associated with anemia.[32,39,40] Al‑Zain studied the impact of socioeconomic conditions and intestinal parasitic infection on hemoglobin level among children aged 2–15 years in Um‑Unnasser village, North Gaza, Palestine. He found that 25% were anemic, and the prevalence rate of anemia was highest in children aged below 6 years.[41] In another study in Gaza Strip, Al‑Agha and Teodorescu studied the prevalence of anemia, nutritional indices and intestinal parasitic infestation in primary school children aged 6–11 years. They found an association between anemia and intestinal parasitic infestation in those children who manifested mainly by intestinal parasites E. histolytica and G. lamblia. Furthermore, they showed a high prevalence of anemia in children suffered from malnutrition along with intestinal parasitic infestation.[31]

Iron deficiency anemia seen in diarrheal and non‑diarrheal cases suggests that nutritional anemia may be prevalent in this population, which may aggravate the clinical symptoms.

Infections are a well‑recognized cause of mild to moderate anemia. Several studies have demonstrated that even mild infections can induce a significant decrease in iron levels.[42‑45] The reduction in hemoglobin level during and after acute or chronic inflammatory diseases is due to many factors such as blocking the iron release, reduction in the intestinal absorption of iron and inhibition or inappropriate erythropoietin production.[21] Levy et al. 2005 in a study, conducted in Israel examined the association between anemia and infection among Bedouin infants. They concluded that anemia is a significant and independent risk factor for diarrhea. In Ecuador, Sackey et al. found that children suffered from intestinal parasitic infections had significantly reduced mean hemoglobin levels compared with their noninfected counterparts. Their data indicated that G. lamblia infection had an adverse impact on child linear growth and hemoglobin levels.[39] Moreover, in a recent study performed in Egypt, the frequency of parasites was significantly higher in cases with IDA compared to controls.[46] Furthermore, a study conducted recently to compare hematological indices in cases with Blastocystis hominis infection against healthy controls revealed that the frequency of SI was significantly lower in cases with B. hominis infection compared to controls.[45]

Ali and Zuberi in Pakistan investigated the presence or absence of any association between low birth weights, recurrent diarrhea or recurrent acute respiratory infections with IDA in Pakistani children aged 1–2 years. They found that there was no statistically significant difference of recurrent diarrhea between anemic and nonanemic children at 1–2 years age.[47] Another study in Pakistan conducted to determine the clinical pattern of infections in admitted malnourished children. A total of 112 admitted malnourished children with various types of infections aged 3–60 months were enrolled in the study. The authors found that the association of malnutrition and infections among children is an important health issue and the common infections found in malnourished children were acute gastroenteritis (44.6%), followed by enteric protozoa and helminthic infections (23%).[48]

Study limitation

The generalizability of above results is subject to certain limitations. For instance, the difficulty in measuring serum ferritin levels and using low transferrin saturation as the marker of iron deficiency could interfere with anemia of inflammation.

Conclusion

Diarrhea remains a health problem in children in Gaza. This study highlights quite a number of the enteric pathogens that cause community gastroenteritis among kindergarten children in Gaza and their possible effect on hemoglobin concentration and TIBC. Another cohort study, on infected and healthy population is recommended to determine other causes of community gastroenteritis and their possible effect on hematological indices.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Richard Proctor, Faculty of Medicine, Wisconsin University, USA, and Prof. Mahmoud Sirdah, Faculty of Science, Al Azhar University‑Gaza, Palestine, for their fruitful suggestions and critically reviewing this manuscript.

References

- Youssef M, Shurman A, Bougnoux M, Rawashdeh M, Bretagne S, Strockbine N. Bacterial, viral and parasitic enteric pathogens associated with acute diarrhea in hospitalized children from northern Jordan. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2000;28:257‑63.

- Lorgelly PK, Joshi D, Iturriza Gómara M, Flood C, Hughes CA, Dalrymple J, et al. Infantile gastroenteritis in the community: A cost‑of‑illness study. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:34‑43.

- Navaneethan U, Giannella RA. Mechanisms of infectious diarrhea. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;5:637‑47.

- Frühwirth M, Heininger U, Ehlken B, Petersen G, Laubereau B, Moll‑Schüler I, et al. International variation in disease burden of Rotavirus gastroenteritis in children with community‑ and nosocomially acquired infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001;20:784‑91.

- O’Ryan M, Prado V, Pickering LK. A millennium update on pediatric diarrheal illness in the developing world. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2005;16:125‑36.

- Parashar UD, Bresee JS, Glass RI. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease in children. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:236.

- Elliott EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children. BMJ 2007;334:35‑40.

- Chao HC, Chen CC, Chen SY, Chiu CH. Bacterial enteric infections in children: Etiology, clinical manifestations and antimicrobial therapy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2006;4:629‑38.

- Jansen A, Stark K, Kunkel J, Schreier E, Ignatius R, Liesenfeld O, et al. Aetiology of community‑acquired, acute gastroenteritis in hospitalised adults: A prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2008;8:143.

- Karsten C, Baumgarte S, Friedrich AW, von Eiff C, Becker K, Wosniok W, et al. Incidence and risk factors for community‑acquired acute gastroenteritis in north‑west Germany in 2004. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2009;28:935‑43.

- Samie A, Guerrant RL, Barrett L, Bessong PO, Igumbor EO, Obi CL. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic and bacterial pathogens in diarrhoeal and non‑diarroeal human stools from Vhembe district, South Africa. J Health Popul Nutr 2009;27:739‑45.

- Abu Elamreen FH, Abed AA, Sharif FA. Detection and identification of bacterial enteropathogens by polymerase chain reaction and conventional techniques in childhood acute gastroenteritis in Gaza, Palestine. Int J Infect Dis 2007;11:501‑7.

- Ngui R, Lim YA, Chong Kin L, Sek Chuen C, Jaffar S. Association between anaemia, iron deficiency anaemia, neglected parasitic infections and socioeconomic factors in rural children of West Malaysia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1550.

- Assefa S, Mossie A, Hamza L. Prevalence and severity of anemia among school children in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Hematol 2014;14:3.

- Righetti AA, Koua AY, Adiossan LG, Glinz D, Hurrell RF,N’goran EK, et al. Etiology of anemia among infants, school‑aged children, and young non‑pregnant women in different settings of South‑Central Cote d’Ivoire. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;87:425‑34.

- Foote EM, Sullivan KM, Ruth LJ, Oremo J, Sadumah I, Williams TN, et al. Determinants of anemia among preschool children in rural, western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;88:757‑64.

- Tielsch JM, Khatry SK, Stoltzfus RJ, Katz J, LeClerq SC, Adhikari R, et al. Effect of routine prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on preschool child mortality in southern Nepal: Community‑based, cluster‑randomised, placebo‑controlled trial. Lancet 2006;367:144‑52.

- Charles CV, Summerlee AJ, Dewey CE. Anemia in Cambodia: Prevalence, etiology and research needs. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2012;21:171‑81.

- Palti H, Pevsner B, Adler B. Does anemia in infancy affect achievement on developmental and intelligence tests? Hum Biol 1983;55:183‑94.

- Nurdia DS, Sumarni S, Suyoko, Hakim M, Winkvist A. Impact of intestinal helminth infection on anemia and iron status during pregnancy: A community based study in Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2001;32:14‑22.

- Levy A, Fraser D, Rosen SD, Dagan R, Deckelbaum RJ, Coles C, et al. Anemia as a risk factor for infectious diseases in infants and toddlers: Results from a prospective study. Eur J Epidemiol 2005;20:277‑84.

- Gisbert JP, Gomollón F. Classification of anemia for gastroenterologists. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4627‑37.

- Gomollón F, Gisbert JP. Anemia and inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4659‑65.

- Bayraktar UD, Bayraktar S. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia associated with gastrointestinal tract diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:2720‑5.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS 2012). Available from: http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/site/512/default. aspx?tabID=512 and lang=en and ItemID=788 and mid=3171 and wversion=Staging. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 15].

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards For Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI M100‑S20. Wayne PA: CLSI; 2010.

- Shek CC, Swaminathan R. A cost effective approach to the biochemical diagnosis of iron deficiency. J Med 1990;21:313‑22.

- World health Organization (WHO). Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva: World Health Organization, (WHO/NMH/NHD/ MNM/11.1); 2011.

- WHO, UNICEF, UNU. Iron Deficiency Anaemia: Assessment,Prevention and Control, A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, (WHO/NHD/01.3); 2001.

- Reither K, Ignatius R, Weitzel T, Seidu‑Korkor A, Anyidoho L, Saad E, et al. Acute childhood diarrhoea in northern Ghana: Epidemiological, clinical and microbiological characteristics. BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:104.

- al‑Agha R, Teodorescu I. Intestinal parasites infestation and anemia in primary school children in Gaza Governorates – Palestine. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol 2000;59:131‑43.

- Shubair ME, Yassin MM, al‑Hindi AI, al‑Wahaidi AA, Jadallah SY, Abu Shaaban N al‑D. Intestinal parasites in relation to haemoglobin level and nutritional status of school children in Gaza. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 2000;30:365‑75.

- Abdeen Z, Greenough G, Shahin M, Tayback M. Nutritional Assessment of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Jerusalem, Palestine: Al‑Quds University Publication; 2003.

- Alzain BF, Sharma ON. Hemoglobin levels and protozoan parasitic infection in school children of Udiapur city (India). J Al Azhar Univ Gaza 2006;8:35‑40.

- Hussein AS. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among school children in northern districts of West Bank‑Palestine. Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:240‑4.

- Selmi A, Al‑Hindi A. Anaemia among school children aged 6‑11 years old in Gaza Strip, Palestine. Ann Alquds Med 2011;7:27‑32.

- Radi SM, El‑Sayed NA, Nofal LM, Abdeen ZA. Ongoing deterioration of the nutritional status of Palestinian preschool children in Gaza under the Israeli siege. East Mediterr Health J 2013;19:234‑41.

- Sirdah MM, Yaghi A, Yaghi AR. Iron deficiency anemia among kindergarten children living in the marginalized areas of Gaza Strip, Palestine. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 2014;36:132‑8.

- Sackey ME, Weigel MM, Armijos RX. Predictors and nutritional consequences of intestinal parasitic infections in rural Ecuadorian children. J Trop Pediatr 2003;49:17‑23.

- Yavasoglu I, Kadikoylu G, Uysal H, Ertug S, Bolaman Z. Is Blastocystis hominis a new etiologic factor or a coincidence iniron deficiency anemia? Eur J Haematol 2008;81:47‑50.

- Al‑Zain BF. Impact of socioeconomic conditions and parasitic infection on hemoglobin level among children in Um‑Unnasser village, Gaza strip. Turk J Med Sci 2009;39:53‑8.

- Sipahi T, Köksal T, Tavil B, Akar N. The effects of acute infection on hematological parameters. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2004;21:513‑20.

- Ballin A, Lotan A, Serour F, Ovental A, Boaz M, Senecky Y, et al. Anemia of acute infection in hospitalized children‑no evidence of hemolysis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2009;31:750‑2.

- Ballin A, Senecky Y, Rubinstein U, Schaefer E, Peri R, Amsel S, et al. Anemia associated with acute infection in children. Isr Med Assoc J 2012;14:484‑7.

- Javaherizadeh H, Khademvatan S, Soltani S, Torabizadeh M,Yousefi E. Distribution of haematological indices among subjects with Blastocystis hominis infection compared to controls. Prz Gastroenterol 2014;9:38‑42.

- El Deeb HK, Khodeer S. Blastocystis spp: Frequency and subtype distribution in iron deficiency anemic versus non‑anemic subjects from Egypt. J Parasitol 2013;99:599‑602.

- Ali NS, Zuberi RW. Association of iron deficiency anaemia in children of 1‑2 years of age with low birth weight, recurrent diarrhoea or recurrent respiratory tract infection – A myth or fact? J Pak Med Assoc 2003;53:133‑6.

- Shabanaejaz M, Rasheed A, Zehra H. Clinical pattern of infection in malnourished children. Pediatrics 2010;16:252‑6.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.