Post-Myocardial Infarction Left Ventricular Free Wall Rupture: A Review

2 Department of Cardiology, University of Alexandria, Egypt

3 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Alexandria, Egypt

4 Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA

Citation: Abdelnaby M, et al. Post-myocardial Infarction Left Ventricular Free Wall Rupture: Review article. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2017; 7: 368-372

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Left ventricular free wall rupture (LVFWR) is a rare striking complication of acute myocardial infarction [AMI]. It can occur in one of two types: either acute lethal form or a subacute form where a blood clot in rare circumstances seals the defect and results in the formation of a ventricular pseudoaneurysm. A high index of suspicion and close monitoring of patient’s symptoms and signs are necessary for diagnosis. Urgent Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of AMI complications such as LVFWR. Multi- Detector Computed Tomography (MDCT) is a suitable alternative if the diagnosis is doubtful or to exclude other etiologies of hemopericardium. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) is mainly used in stable patients with subacute LVFWR or pseudoaneurysm for more defined tissue characterization. Pericardiocentesis is not a routine procedure and it is done only as an emergency desperate measure in hemodynamically unstable patients while a surgical repair is prepared. Despite the high surgical mortality rates, urgent surgical repair is still the rule for treatment of LVFWR using pericardial patch closure or less frequently infarctectomy with patch placement and ventricular wall reconstruction. Recently sutureless techniques started to play a major role with improved mortality in patients with LVFWR with careful follow-up is required for the risk of recurrent rupture or pseudoaneurysm formation.

Keywords

Left ventricular free wall rupture (LVFWR); Acute myocardial infarction (AMI); Thrombolytic therapy; Pericardiocentesis; Infarctectomy; Sutureless techniques

Introduction

Aim of the review

The aim of this review article is to highlight one of the gravest complications of AMI which is LVFWR and to enlighten physicians about its incidence, types, risk factors, clinical presentations, diagnostic modalities and different treatment options.

Incidence

One of the life-threatening complications of AMI is myocardial rupture which is directly responsible for mortality in 8% of AMI patients. [1] A fatal yet quite rare form of this complication is LVFWR, that takes place in about 2% of cases. [2] but nowadays in the era of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), it is less frequently encountered. [3] Still, it is a lethal complication. [4]

Risk factors

The classical risk factors of LVFWR are elderly patients (usually =55 years and commonly in-between 65 and 70 years) [5-8], female gender (although no definitive sex bias has been reported but relatively more common in females due to lower reported incidence of AMI in females). [9-12] With higher incidence of arterial hypertension [9,13-15] and no previous anginal attacks (due to lack of collateral circulation), [9,16,17] Also in the first episode of transmural anterior or lateral AMI [9,14-16] without overt heart failure symptoms. [4,7,9,14,16,18] Although urgent reperfusion either by PCI or less frequently used thrombolytic therapies is considered a necessity to reduce the risk of LVFWR but studies showed that late or failed thrombolysis are usually linked to increased rates of LVFWR. [19-21] Also, PCI independently reduces the risk of LVFWR in comparison with thrombolysis. [22] (clinical characteristics of LVFWR patients are summarized in Table 1. In addition to classical risk factors, other triggering factors for LVFWR are the presence of persistent arterial hypertension (? 150 mm Hg) during the 1st 24 hours of the acute infarction while in hospital at rest, and any undue physical effort such as persistent coughing, vomiting, or agitation [10,11,18,23-25] [Table 2].

| Age >55 years (67 average) |

| Female gender |

| First trans-mural anterior or lateral myocardial infarction |

| No overt heart failure symptoms (Killip class I or II*) |

| Persistent ST-segment elevation |

| Persistent or recurrent chest pain |

| Sudden or progressive hypotension or sudden electromechanical dissociation |

Table 1: Clinical characteristics of LVFWR patients.

| Delayed hospital admission (> 12–24 hours) |

| Persistent systemic hypertension during first > 10–24 hours |

| “Unusual” in-hospital physical effort (agitation, repetitive vomiting or coughing, etc) |

| Extension of myocardial infarction |

| Expansion of myocardial infarction |

Table 2: Additional factors facilitating LVFWR. [27]

Killip classification [26] is used for risk stratification of AMI patients into:

• Killip Class I: No clinical signs of heart failure

• Killip Class II: Mild heart failure

• Killip Class III: Acute pulmonary oedema

• Killip Class IV: Cardiogenic shock

Clinical Presentation

LVFWR classically causes manifestations within the 1st day but it can occur up to 1 week after an attack of AMI. [12] The clinical scenario depends on the rate and the amount of the accumulated pericardial bleeding. In most cases of LVFWR sudden hemodynamic collapse is followed by death. In some cases, a blood clot will seal pericardial leaks and form a left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. [27,28] The hallmark of the subacute variant of LVFWR is slow repetitive intermittent bleeding, which occurs in one-third of cases. [29,30] Dissimilar to classic LVFWR patients, the subacute variant patients may endure until emergency surgery is arranged. [12] Several studies have tried to describe the warning signs and symptoms of fatal LVFWR. [10,20,29-31] Prodromal manifestations include persistent chest pain, intractable vomiting, restlessness, also electrocardiogram (ECG) signs as persistent S-T segment elevation, and positive T wave deflection that persists for 72 hours after the onset of chest pain. [10,29] Other classic signs of cardiac tamponade, including pulsus paradoxus and diastolic pressure equalization, may not exist in most of the cases [Table 3]. [30]

| Time of occurrence | |

|---|---|

| Early rupture (= 48 hours) | Delayed hospital admission |

| Persistent pain (> 4–6 hours) | |

| Acute arterial hypertension | |

| Frank and persistent ST-segment elevation | |

| Late rupture (> 48 hours) | Recurrent chest pain |

| Persistent ST segment elevation | |

| “Undue” physical exercise | |

| Infarct extension | |

| Infarct expansion | |

| Form of presentation | |

| Acute rupture | Acute tamponade with sudden electromechanical dissociation or severe hypotension |

| Subacute rupture | Moderate to severe pericardial effusion: |

| (A) with tamponade and haemodynamic compromise with modest or progressive hypotension | |

| (B) without tamponade | |

Table 3: Types of LVFWR according to time of occurrence or form of presentation. [27]

Diagnosis

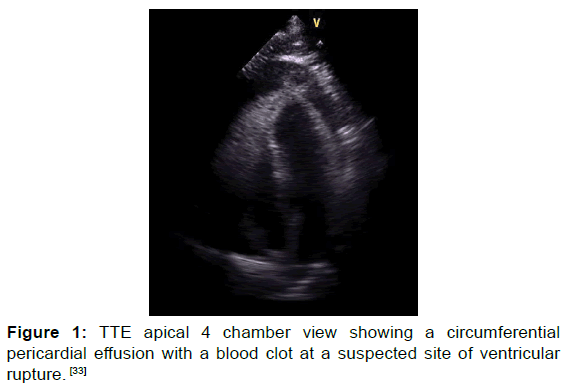

TTE is still the gold standard for the definitive diagnosis of LVFWR. A pericardial effusion or intrapericardial echoes are the usual findings, less commonly a right-sided heart collapse or the actual tear may be seen. TTE offers a 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity for LVFWR diagnosis [Figures 1 and 2]. [30,32,33]

Figure 1: TTE apical 4 chamber view showing a circumferential pericardial effusion with a blood clot at a suspected site of ventricular rupture. [33]

Figure 2: TTE apical 4 chamber view showing apical LVFWR. [33]

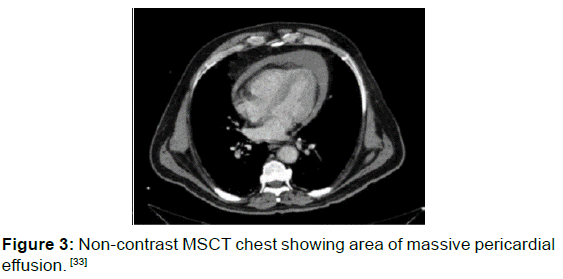

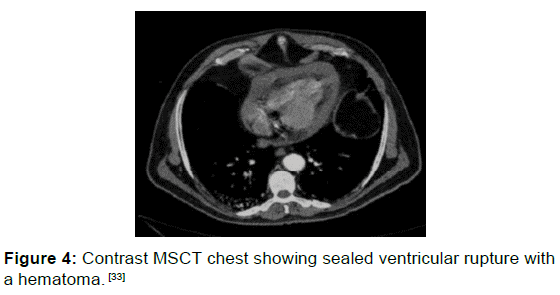

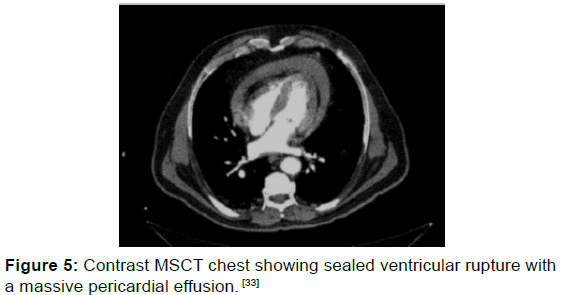

MDCT has been shown to be an effective modality for the detection of LVFWR and it may be beneficial to guide the diagnosis especially in cases when the diagnosis is doubtful or to exclude other causes of hemopericardium such as aortic dissection [Figures 3, 4 and 5]. [34,35]

Figure 3: Non-contrast MSCT chest showing area of massive pericardial effusion. [33]

Figure 4: Contrast MSCT chest showing sealed ventricular rupture with a hematoma. [33]

Figure 5: Contrast MSCT chest showing sealed ventricular rupture with a massive pericardial effusion. [33]

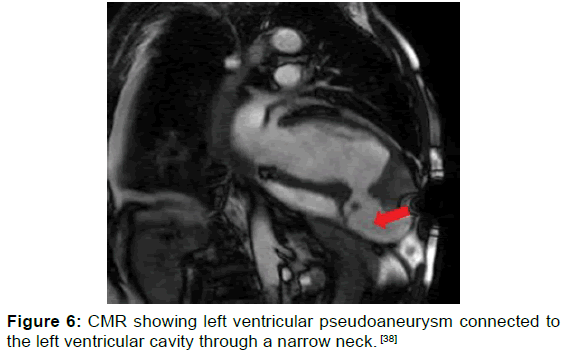

CMR is definitely not the modality of choice in acute settings when hemodynamic instability is the case, however, in subacute hemodynamically stable cases, CMR can help to determine the specific anatomical location of LVFWR, ventricular true or pseudoaneurysms, therefore planned surgical intervention can be prepared. In addition, it may delineate areas of ischemic myocardium even in the absence of ECG changes consistent with ischemia also it can show areas of the myocardium at risk of impending rupture [Figure 6 and Table 4]. [36,37]

| Acute phase (sequential course according to response) |

|---|

| Oxygenation/ventilation |

| Colloid infusion |

| Dobutamine |

| Pericardiocentesis if hemodynamically unstable (start with 10–50 ml) |

| Cardiac massage |

| Surgical treatment |

| Maintenance phase |

| Withdrawal of dobutamine |

| Blood pressure control with ß blockers (systolic 100–120 mm Hg) |

| Prolonged rest (5–10 days) |

| Avoidance of physical exercise |

| Echocardiography (every 2–3 days) |

Table 4: Management of acute and subacute free wall rupture. [27]

Some articles suggested that conservative medical therapy might be of value in patients with LVFWR and pseudoaneurysm formation especially when hemodynamic stability is rapidly achieved. [38-40]

Rapid fluid infusion and administration of positive inotropic agents are considered the cornerstone of the temporary supportive measures until definitive management is planned. [40]

Emergency pericardiocentesis is not recommended except as a final measure to regain hemodynamic stability if cardiac tamponade occurred while urgent surgery is arranged as it bears the risk of chamber perforation and it may theoretically compromise the effect of a blood clot due to displacement or decompression of the previously contained rupture with further bleeding and accumulation of pericardial effusion. [12,33,40]

Discussion

Intra-aortic balloon pump is a widely used therapy in cases of ventricular septal rupture complicating AMI [41] However, its benefit in LVFWR is yet still debatable except in cases of persistent ischemia and/or LV pump failure. [12,40] Although the highly reported operative mortality which is 40% of cases [42-44] but the ultimate management of LVFWR is emergency surgical repair: the widely accepted surgical option which is associated with a better outcome is LVFWR closure by pericardial patch placement using either biological glue or epicardial sutures. [45,46] Infarctectomy with patch placement and aneursymectomy with ventricular wall reconstruction are less commonly used surgical techniques. [42,45] Pledgeted sutures without infarctectomy, and pericardial, Dacron, Goretex, or Teflon patches adhered with biologic glue or sutures. [30] Recently there is a shift towards the sutureless techniques because of its simplicity, effectiveness and avoidance of friable myocardial tissue. [47]

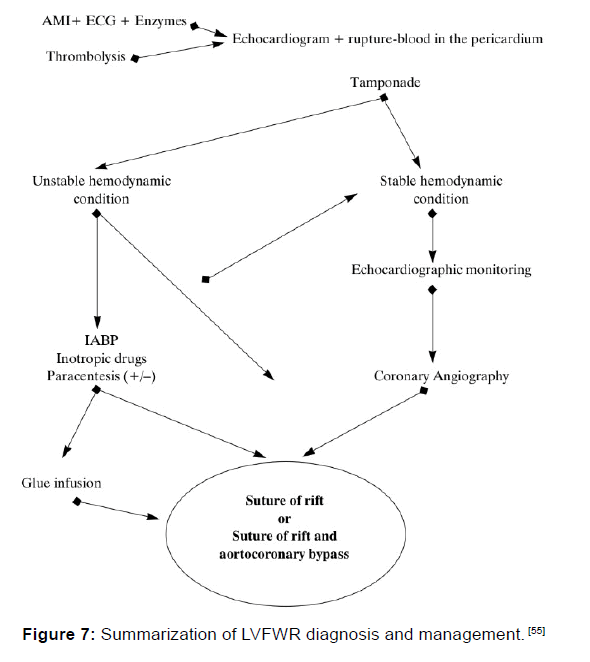

Sutureless techniques include a fibrin tissue-adhesive collagen fleece TachoSil® (Takeda, Osaka, Japan) combined with bovine pericardial patch anchored by fibrin glue in a case of oozing postinfarction cardiac rupture, [47] Teflon felt (C R Bard Inc, Billerica, MA, USA) attached using BioGlue (Cryolife Inc., Kennesaw, GA, USA) used for an acute LVFWR, [48] gelatinresorcin- formalin (GRF glue: Cardial, Saint-Etienne, France) applied to a bovine pericardial patch (Impra, Tempe, AZ, USA) [49] and collagen fleece with fibrinogen-based impregnation (Tachocomb; Nycomed Pharma, Linz, Austria). [50] Although sutureless repair is promising in most cases, careful followup is mandatory because of the risk of recurrent rupture or ventricular aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm formation at the site of the sutureless repair in some patients. [47,51] Urgent coronary angiography to determine coronary anatomy for a planned coronary artery bypass is permitted in the hemodynamically stable subacute patients [52] Although the combination of surgical repair with coronary artery bypass grafting is most often advised, off-pump repair has been reported. [52] This approach is very beneficial because 80% of patients who had LVFWR are also multi-vessel coronary artery disease patients. [52,53] Some reports claim that operative mortality is 15% while the 5 years postoperative survival rates are 85% after successful surgical repair [Figure 7]. [54,55]

Conclusion

LVFWR is a disastrous complication that is rarely encountered nowadays in the era of PCI. A high index of clinical suspicion together with bedside TTE is necessary for prompt diagnosis. Despite the high surgical risk, surgical repair remains the gold standard for managing this rare condition. Recent advances in surgical techniques such as sutureless techniques are associated with better outcome.

Conflict of Interest

All authors disclose that there was no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Reddy SG, Roberts WC. Frequency of rupture of the left ventricular free wall or ventricular septum among necropsy cases of fatal acute myocardial infarction since introduction of coronary care units. The American journal of cardiology. 1989; 63: 906-911.

- Moreno R, De Sá EL, López-Sendón JL, Garci´a E, Soriano J, Abeytua M, et al. Frequency of left ventricular free-wall rupture in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty. The American journal of cardiology. 2000; 85: 757-760.

- Yip HK, Wu CJ, Chang HW, Wang CP, Cheng CI, Chua S, et al. Cardiac rupture complicating acute myocardial infarction in the direct percutaneous coronary intervention reperfusion era. CHEST Journal. 2003; 124: 565-571.

- Keeley EC, De Lemos JA. Free wall rupture in the elderly: deleterious effect of fibrinolytic therapy on the ageing heart The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology. Oxford University Press; 2005.

- London RE, London SB. Rupture of the heart. Circulation. 1965; 31: 202-208.

- Bates RJ, Beutler S, Resnekov L, Anagnostopoulos C. Cardiac rupture—Challenge in diagnosis and management. The American journal of cardiology. 1977; 40: 429-437.

- Rasmussen S, Leth A, Kjøller E, Pedersen A. Cardiac rupture in acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1979; 205: 11-16.

- Dellborg M, Held P, Swedberg K, Vedin A. Rupture of the myocardium. Occurrence and risk factors. Heart. 1985; 54: 11-16.

- Mann JM, Roberts WC. Rupture of the left ventricular free wall during acute myocardial infarction: analysis of 138 necropsy patients and comparison with 50 necropsy patients with acute myocardial infarction without rupture. The American journal of cardiology. 1988; 62: 847-859.

- Oliva PB, Hammill SC, Edwards WD. Cardiac rupture, a clinically predictable complication of acute myocardial infarction: Report of 70 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1993; 22: 720-726.

- Figueras J, Cortadellas J, Calvo F, Soler-Soler J. Relevance of delayed hospital admission on development of cardiac rupture during acute myocardial infarction: study in 225 patients with free wall, septal or papillary muscle rupture. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1998; 32: 135-139.

- Purcaro A, Costantini C, Ciampani N, Mazzanti M, Silenzi C, Gili A, et al. Diagnostic criteria and management of subacute ventricular free wall rupture complicating acute myocardial infarction. The American journal of cardiology. 1997; 80: 397-405.

- Shapira I, Isakov A, Burke M, Almog C. Cardiac rupture in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chest. 1987; 92: 219-223.

- Naeim F, De La Maza LM, Robbins SL. Cardiac rupture during myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1972; 45: 1231-1239.

- Wessler S, Zoll PM, Schlesinger MJ. The pathogenesis of spontaneous cardiac rupture. Circulation. 1952; 6: 334-351.

- Figueras J, Curos A, Cortadellas J, Sans M, Soler-Soler J. Relevance of electrocardiographic findings, heart failure, and infarct site in assessing risk and timing of left ventricular free wall rupture during acute myocardial infarction. The American journal of cardiology. 1995; 76: 543-547.

- Nakano T, Konishi T, Takezawa H. Potential prevention of myocardial rupture resulting from acute myocardial infarction. Clinical cardiology. 1985; 8: 199-204.

- Friedman HS, Kuhn LA, Katz AM. Clinical and electrocardiographic features of cardiac rupture following acute myocardial infarction. The American Journal of Medicine. 1971; 50: 709-720.

- Becker RC, Charlesworth A, Wilcox RG, Hampton J, Skene A, Gore JM, et al. Cardiac rupture associated with thrombolytic therapy: impact of time to treatment in the Late Assessment of Thrombolytic Efficacy [LATE] study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1995; 25: 1063-1068.

- Becker RC, Gore JM, Lambrew C, Weaver WD, Rubison RM, French WJ, et al. A composite view of cardiac rupture in the United States National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1996; 27: 1321-1326.

- Ohishi F, Hayasaki K, Honda T. Effect of thrombolysis on rupture of the left ventricular free wall following acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Cardiology. 1996; 28: 27-32.

- Moreno R, López-Sendón J, García E, de Isla LP, De Sá EL, Ortega A, et al. Primary angioplasty reduces the risk of left ventricular free wall rupture compared with thrombolysis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002; 39: 598-603.

- Jetter WW, White PD. Rupture of the heart in patients in mental institutions. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1944; 21: 783-802.

- Lewis AJ, Burchell HB, Titus JL. Clinical and pathologic features of postinfarction cardiac rupture*. The American journal of cardiology. 1969; 23: 43-53.

- Lauch E. Pathogenesis of cardiac rupture. Arch Pathol. 1967; 84: 264-271.

- Rott D, Behar S, Gottlieb S, Boyko V, Hod H, Group ITS. Usefulness of the Killip classification for early risk stratification of patients with acute myocardial infarction in the 1990s compared with those treated in the 1980s 1. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1997; 80: 859-864.

- Figueras J, Cortadellas J, Soler-Soler J. Left ventricular free wall rupture: clinical presentation and management. Heart. 2000;83 [5] :499-504.

- Mahilmaran A NP, Sheshadri M, Sudarsana G, Abraham KA. Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2002 [ Jun 1;29 [2]. ].

- Raitt MH, Kraft CD, Gardner CJ, Pearlman AS, Otto CM. Subacute ventricular free wall rupture complicating myocardial infarction. American heart journal. 1993;126 [4] :946-55.

- López-Sendón J, González A, De Sá EL, Coma-Canella I, Roldán I, Domínguez F, et al. Diagnosis of subacute ventricular wall rupture after acute myocardial infarction: sensitivity and specificity of clinical, hemodynamic and echocardiographic criteria. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1992; 19: 1145-1153.

- Figueras J, Curós A, Cortadellas J, Soler-Soler J. Reliability of electromechanical dissociation in the diagnosis of left ventricular free wall rupture in acute myocardial infarction. American heart journal. 1996; 131: 861-864.

- Mittle S, Makaryus AN, Mangion J. Role of contrast echocardiography in the assessment of myocardial rupture. Echocardiography. 2003; 20: 77-81.

- Abdelnaby MAA, Saleh Y, Haleem MA, El-Amin A, et al. A Rare Case of Fatal Left Ventricular Free Wall Rupture: Case Report and Short Review. J Cardiovasc Dis Diagn. 2017; 5: 290.

- Suzuki R, Mikamo A, Kurazumi H, Hamano K. Left ventricular free wall rupture detected by multidetector computed tomography after mitral valve replacement. Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 2010; 25: 699.

- Crossley R, Morgan-Hughes G, Roobottom C. Post myocardial infarction left ventricular free wall rupture diagnosed by multidetector computed tomography. Heart. 2007; 93: 653.

- Shiyovich A, Nesher L. Contained left ventricular free wall rupture following myocardial infarction. Case reports in critical care. 2012.

- Krishnan U, McCann GP, Hickey M, Schmitt M. Role of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in detecting early adverse remodeling and subacute ventricular wall rupture complicating myocardial infarction. Heart and vessels. 2008; 23: 430-432.

- Abdelnaby M, Almaghraby A, Saleh Y, Hammad B, El-Amin A, El-Fawal S, et al. A case of left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. Journal of Heart and Cardiovascular Research. 2017.

- Moreno R, Gordillo E, Zamorano J, Almeria C, Garcia-Rubira J, Fernandez-Ortiz A, et al. Long term outcome of patients with postinfarction left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. Heart. 2003; 89: 1144-1146.

- Figueras J, Cortadellas J, Evangelista A, Soler-Soler J. Medical management of selected patients with left ventricular free wall rupture during acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997; 29: 512-518.

- Bocchi EA, Vilas-Boas F, Perrone S, Caamaño AG, Clausell N, Moreira MDCV, et al. I Latin American guidelines for the assessment and management of decompensated heart failure. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. 2005; 85:1-48.

- Reardon MJ, Carr CL, Diamond A, Letsou GV, Safi HJ, Espada R, et al. Ischemic left ventricular free wall rupture: prediction, diagnosis, and treatment. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1997; 64: 1509-1513.

- Stryjer D, Friedensohn A, Hendler A. Myocardial rupture in acute myocardial infarction: Urgent management. Heart. 1988; 59: 73-74.

- McMullan M, Kilgore Jr T, Dear Jr H, Hindman S. Sudden blowout rupture of the myocardium after infarction: urgent management. Report of four cases. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1985; 89: 259-263.

- Mantovani V, Vanoli D, Chelazzi P, Lepore V, Ferrarese S, Sala A. Post-infarction cardiac rupture: surgical treatment. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery. 2002; 22: 777-780.

- Padró J, Mesa J, Silvestre J, Larrea J, Caralps J, Cerrón F, et al. Subacute cardiac rupture: repair with a sutureless technique. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1993; 55: 20-24.

- Konarik M, Pokorny M, Pirk J, Netuka I, Szarszoi O, Maly J. New modalities of surgical treatment for postinfarction left ventricular free wall rupture: A case report and literature review. Cor et Vasa. 2015; 57: e359-e361.

- Hsieh YK, Lee CH, Chen YS, Wu IH. Pseudoaneurysm after sutureless repair of left ventricular free wall rupture: Sequential magnetic resonance imaging demonstration. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2015; 38: 174-176.

- Vohra HA, Chaudhry S, Satur CM, Heber M, Butler R, Ridley PD. Sutureless off-pump repair of post-infarction left ventricular free wall rupture. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2006; 1: 11.

- Nishizaki K, Seki T, Fujii A, Nishida Y, Funabiki M, Morikawa Y. Sutureless patch repair for small blowout rupture of the left ventricle after myocardial infarction. The Japanese Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2004; 52: 268-271.

- Aoyagi S, Tayama K, Otsuka H, Okazaki T, Shintani Y, Wada K, et al. Sutureless repair for left ventricular free wall rupture after acute myocardial infarction. Journal of cardiac surgery. 2014; 29: 178-180.

- Park WM, Connery CP, Hochman JS, Tilson MD, Anagnostopoulos CE. Successful repair of myocardial free wall rupture after thrombolytic therapy for acute infarction. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000; 70: 1345-1349.

- Sutherland FW, Guell FJ, Pathi VL, Naik SK. Postinfarction ventricular free wall rupture: strategies for diagnosis and treatment. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1996; 61: 1281-1285.

- Horio N TH, Ikebuchi M, Irie H. Surgical outcomes of left ventricular free wall rupture and ventricular septal perforation after acute myocardial infarction. Japanese Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery. 2014; 43: 305-309.

- Exadaktylos NI, Kranidis AI, Argyriou MO, Charitos CG, Andrikopoulos GK. Left ventricular free wall rupture during acute myocardial infarction: early diagnosis and treatment. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2002; 43: 246-252.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.