Prevalence of Clinical and Radiological Manifestations among COVID-19 Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

2 Medical Intern, Jazan University, Jazan City, Saudi Arabia

3 Medical Intern, Jazan University, Khamis Mushat, Saudi Arabia

4 Medical Intern, Ibn Sina National College, Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia

5 Pediatric Resident, Maternity and Children Hospital, AlQassim City, Saudi Arabia

6 Pediatric Resident, King Khalid University, Abha City, Saudi Arabia

7 General Practitioner, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Aloqbi HS, et al. Prevalence of Clinical and Radiological Manifestations among COVID-19 Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2021;11: 1193-1198.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

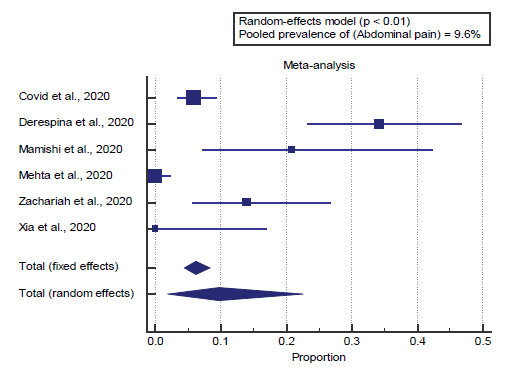

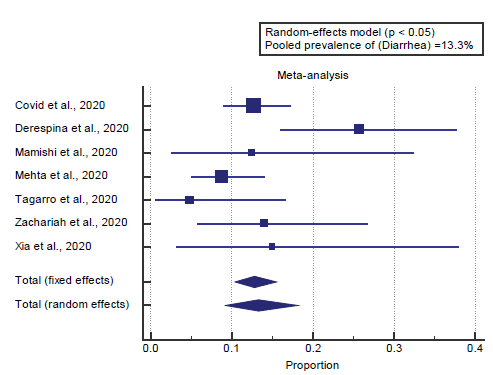

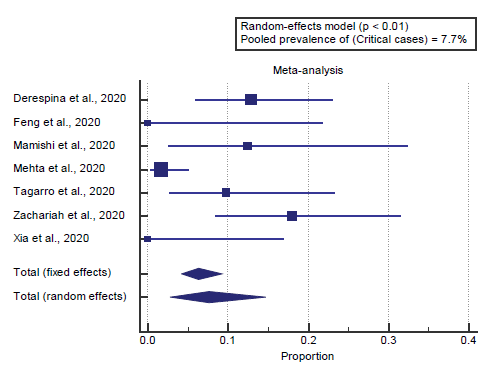

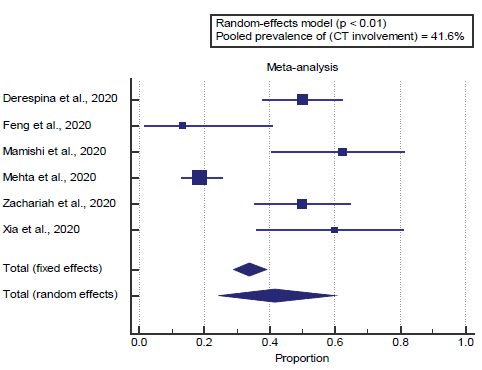

Background: The severity of lung involvement associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection levels from lack of symptoms or slight pneumonia (in 81%) to excessive disease-associated hypoxia (seen in 14%), a critical disease associated with shock, respiration failure, and multi-organ failure (in 5%) or death (2.3%). Aim: This work aims to determine the prevalence of clinical and radiological manifestations among children and adolescents COVID-19 patients. Materials and Methods: A systematic search was performed over different medical databases to identify Pediatrics studies, which studied the outcome of COVID-19 infection in children and adolescents. Using the meta-analysis process, either with fixed or random-effects models, we conducted a meta-analysis on the prevalence of clinical manifestations (e.g., fever, nasal congestion, cough, dyspnea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and critical cases), as primary outcomes, and on radiological manifestations (e.g., CT involvement – ground-glass opacities), as a secondary outcome. pooled prevalence of abdominal pain = 9.6%, pooled prevalence of critical cases = 7.7% Results: Eight studies were identified involving 682 patients. The meta-analysis process revealed a pooled prevalence of fever = 61.1%, a pooled prevalence of nasal congestion = 8%, pooled prevalence of cough = 49.7%, pooled prevalence of dyspnea = 21.4%, pooled prevalence of diarrhea = 13.3%, pooled prevalence of critical cases = 7.7%. Concerning the secondary outcome measures, the pooled prevalence of CT involvement = 41.6%. Conclusion: To conclude, COVID-19 disease cause different manifestations in children such as fever and respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnea, organizing pneumonia and decreased pulmonary function.

Keywords

Manifestations; COVID-19; Children; Adolescents

Introduction

The world health organization (WHO) in 2012 discovered the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection. [1] The current pandemic as a result of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), continues to spread. Even though the respiratory complications of SARSCoV- 2 have been described, the effect on the gastrointestinal and hepatic systems remains unknown, with conflicting levels referred to in preliminary cases from China and Singapore. They purposed to signify the gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with SARS-CoV-2. [2] Several risk factors are associated with this disease. In a cohort study, advanced age was found to be significantly correlated with overall COVID-19 prevalence, which is consistent with the higher incidence. The sex is another risk factor as a higher prevalence has been seen in men than women. [3] The severity of lung involvement associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection levels from lack of symptoms or slight pneumonia (in 81%) to excessive disease-associated hypoxia (seen in 14%), a critical disease associated with shock, respiration failure, and multi-organ failure (in 5%) or death (2.3%). It is the most common critical disease manifestation. Patients might also gift with a dry cough, fever, sputum manufacturing, fatigue, and dyspnea, and the pronounced frequency varies primarily based on the cohort studied. [4] This work aims to determine the prevalence of clinical and radiological manifestations among children and adolescents COVID-19 patients.

Literature Review

Our review came following the (PRISMA) statement guidelines. [5]

Study eligibility

The included studies should be in English, a journal published article, and a human study describing children and adolescents COVID-19 patients. The excluded studies were non-English, or animal studies, or describing adult COVID-19 patients.

Study identification

Basic searching was done over the PubMed, Cochrane library, and Google scholar using the following keywords: Manifestations, COVID-19, Children and adolescents.

Data extraction and synthesis

RCTs, clinical trials, and comparative studies, which studied the outcome of children and adolescents COVID-19 patients, will be reviewed.

Outcome measures: the prevalence of clinical manifestations (e.g., fever, nasal congestion, cough, dyspnea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and critical cases), as primary outcomes, and on radiological manifestations (e.g., CT involvement – groundglass opacities), as a secondary outcome.

Study selection

We found 190 records, 111 excluded because of the title; 79 articles are searched for eligibility by full-text review; 35 articles cannot be accessed; 16 studies were reviews and case reports; 20 were not describing functional outcome; studies leaving 8 studies that met all inclusion criteria.

Statistical analysis

Pooled Proportions (%), with 95% confidence intervals (CI) assessed, using statistical package (MedCalc, Belgium). The meta-analysis process established via I2-statistics (either the fixed-effects model or the random-effects model), according to Q test for heterogeneity.

Results

The included studies were all published in 2020 [Table 1]. [6-13]

| N | Author | Number of patients | Age (average years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| 1 | Covid et al. [6] | 291 | -- |

| 2 | Derespina et al. [7] | 70 | 15 |

| 3 | Feng et al. [8] | 15 | 8 |

| 4 | Mamishi et al. [9] | 24 | 6 |

| 5 | Mehta et al. [10] | 171 | 7 |

| 6 | Tagarro et al. [11] | 41 | 1 |

| 7 | Zachariah et al. [12] | 50 | 12 |

| 8 | Xia et al. [13] | 20 | 2 |

| #Studies arranged alphabetically. | |||

Table 1: Patients and study characteristics.

Regarding patients’ characteristics, the total number of patients in all the included studies was 682 patients, and their average age was (7.3) years [Table 1].

A meta-analysis study was done on 8 studies; with an overall number of patients (N=682) [Table 2]. [6-13]

| N | Author | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | Nasal congestion | Cough | Dyspnea | Abdominal pain | Diarrhea | Critical cases | CT involvement | ||

| 1 | Covid et al. [6] | 163 | 21 | 158 | 39 | 17 | 37 | -- | -- |

| 2 | Derespina et al. [7] | 51 | 9 | 50 | 45 | 24 | 18 | 9 | 35 |

| 3 | Feng et al. [8] | 5 | -- | 1 | -- | -- | -- | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | Mamishi et al. [9] | 24 | 1 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 15 |

| 5 | Mehta et al. [10] | 71 | 9 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 3 | 32 |

| 6 | Tagarro et al. [11] | 11 | -- | 14 | -- | -- | 2 | 4 | -- |

| 7 | Zachariah et al. [12] | 40 | 6 | 23 | 17 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 25 |

| 8 | Xia et al. [13] | 12 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

Table 2: Summary of outcome measures in all studies.

Each outcome was measured by:

Proportions (%)

• For the prevalence of fever.

• For the prevalence of nasal congestion.

• For the prevalence of cough.

• For the prevalence of dyspnea.

• For the prevalence of abdominal pain.

• For the prevalence of diarrhea.

• For the prevalence of critical cases.

• For the prevalence of CT involvement.

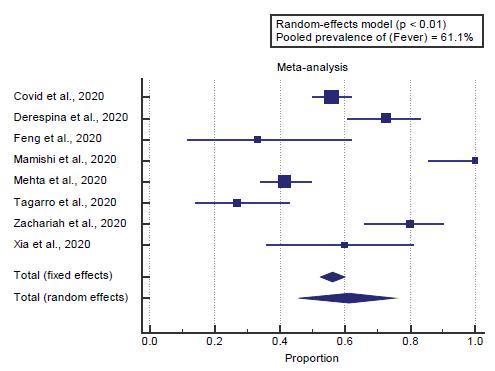

Concerning the primary outcome measure, we found all 8 studies reported fever. I2 (inconsistency) was 92.5%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0. 0001), so random-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of fever=61.1% (p < 0.01), [Figure 1].

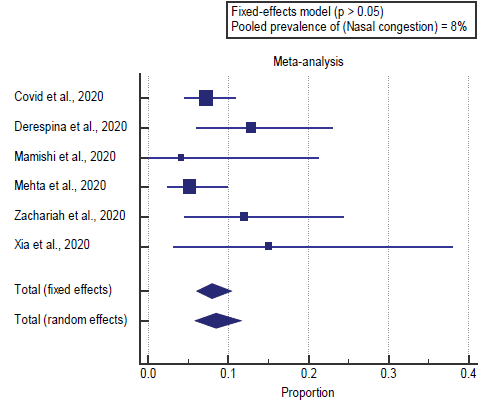

We found all 8 studies reported nasal congestion. I2 (inconsistency) was 28%, Q test for heterogeneity (p > 0.05), so fixed-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of nasal congestion=8% (p > 0.05), [Figure 2].

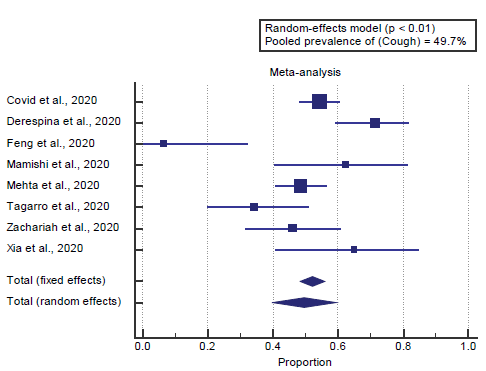

We found all 8 studies reported cough. I2 (inconsistency) was 81%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so randomeffects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of cough=49.7% (p < 0.001), [Figure 3].

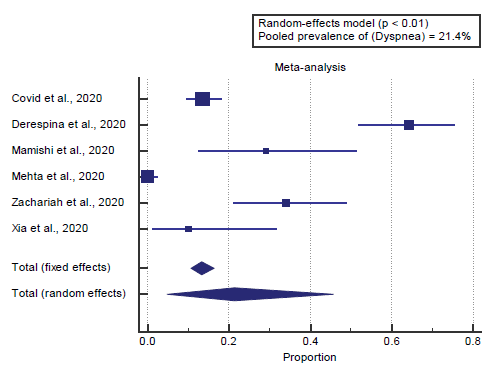

We found 6 studies reported dyspnea. I2 (inconsistency) was 97.2%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so randomeffects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of dyspnea=21.4% (p < 0.05), [Figure 4].

We found 6 studies reported abdominal pain. I2 (inconsistency) was 94%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so randomeffects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of abdominal pain=9.6% (p < 0.05), [Figure 5].

We found 7 studies reported diarrhea. I2 (inconsistency) was 56%, Q test for heterogeneity (p=0.034), so random-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of diarrhea=13.3% (p < 0.05), [Figure 6].

We found 7 studies reported critical cases. I2 (inconsistency) was 76.6%, Q test for heterogeneity (p=0.0003), so randomeffects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of critical cases=7.7% (p < 0.05), [Figure 7].

Concerning the secondary outcome measures, we found 6 studies reported CT involvement. I2 (inconsistency) was 90%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so random-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of CT involvement=41.6% (p < 0.05), [Figure 8].

Discussion

This work aims to determine the prevalence of clinical and radiological manifestations among children and adolescents COVID-19 patients. The included studies were all published in 2020. Regarding patients’ characteristics, the total number of patients in all the included studies was 682 patients, and their average age was (7.3) years. A meta-analysis study was done on 8 studies; with an overall number of patients (N=682).

Concerning the primary outcome measure, we found all 8 studies reported fever. I2 (inconsistency) was 92.5%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so random-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of fever=61.1% (p < 0.01). Which came in agreement with Mantovani et al., [14] Cholankeril et al., [2] Adhikari et al. [15]

Mantovani et al. reported that, 2855 (mainly Chinese) children and/o adolescents (mean age 6.9 ± 7.0 years; 50.3% males) with COVID-19 disease by PCR testing. Eighteen of the eligible studies provided data on major adverse events, whereas one described only the severity of the disease. Overall, 47 percent of children had a fever (98.6%). [14]

Cholankeril et al. reported that 116 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 were identified. Overall, the average age was 50 years with a higher distribution of males (53.4%) and Caucasians (50.9%). The most common symptoms at presentation included cough (94.8%), fever (76.7%), dyspnea (58%), and myalgias (52.2%). [2]

Adhikari et al. reported that the complete clinical manifestation is not clear yet, as the reported symptoms range from mild to severe, with some cases even resulting in death. The most commonly reported symptoms are fever, cough, myalgia or fatigue, pneumonia, and complicated dyspnea, whereas less commonly reported symptoms to include headache, diarrhea, hemoptysis, runny nose, and phlegm producing cough. [15]

We found all 8 studies reported nasal congestion. I2 (inconsistency) was 28%, Q test for heterogeneity (p > 0.05), so fixed-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of nasal congestion=8% (p > 0.05), which came in agreement with Mantovani et al. [14]

Mantovani et al. reported that, total of 2855 (mainly Chinese) children and/or adolescents (mean age 6.9 ± 7.0 years; 50.3% males) with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 disease by nasopharyngeal swabs47% of children had fever (I2=98.6%), 37% cough (I2=98.6%), 4% diarrhea (I2=92.2%), 2% nasal congestion (I2=87.7%). [14]

We found all 8 studies reported cough. I2 (inconsistency) was 81%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so random-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of cough=49.7% (p < 0.001), which came in agreement with Badawi & Ryoo [1] and Gavriatopoulou et al. [4]

Badawi & Ryoo reported that a meta-analysis of the identified studies showed that the most prevalent clinical symptoms were cough (80. 5% and fever (77. 6%). [1]

Gavriatopoulou et al. reported that a study in China included 1099 patients and demonstrated that the most common symptoms on admission were fever (43.8%) and cough (67.8%). Gastrointestinal symptoms were less common—nausea or vomiting 5% and diarrhea 3.8%, respectively. [4]

We found 6 studies reported dyspnea. I2 (inconsistency) was 97.2%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so randomeffects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of dyspnea=21.4% (p < 0.05), which came in agreement with Badawi & Ryoo, [1] Cholankeril et al. [2] and Lang et al. [16]

Badawi & Ryoo reported that a meta-analysis of the identified studies showed that the most prevalent clinical symptoms were cough (80. 5%, and fever (77. 6%), followed by shortness of breath (68. 8%). [1]

Cholankeril et al. reported that, overall, the median age was 50 years, with a higher distribution of male (53.4%) and white (50.9%) patients. 27.9% of patients were noted to be obese with a body mass index >30 kg/m2. 11.6% of the patients were health care practitioners or allied staff. The most common symptoms at presentation included cough (94.8%), fever (76.7%), dyspnea (58%), and myalgia’s (52.2%). [2]

Lang et al. reported that the average age was 58 ± 19 years and 23 patients (48%) were female [Table 1]. The most common presenting symptoms include cough (71%), fever (60%), and shortness of breath (58%). Hypertension (48%), obesity (44%), history of malignancy (23%), and diabetes (19%) were the four most prevalent comorbidities. No patients had prior liver disease. [16]

We found 6 studies reported abdominal pain. I2 (inconsistency) was 94%, Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so randomeffects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of abdominal pain=9.6% (p < 0.05), which came in agreement with Gavriatopoulou et al. [4]

Gavriatopoulou et al. reported that, in total, 99 patients (48.5%) had gastrointestinal symptoms. The symptoms included anorexia (83.8%), diarrhea (29.3%), vomiting (8.1%) and abdominal pain (4.0%). [4]

We found 7 studies reported diarrhea. I2 (inconsistency) was 56%, Q test for heterogeneity (p=0.034), so random-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of diarrhea=13.3% (p < 0.05), which came in agreement with Cholankeril et al. [2]

Cholankeril et al. reported that gastrointestinal manifestations found in 32% of cases. Loss of appetite in 22.3%, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea in 12% respectively. The average duration of gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting or diarrhea was 1 day; which was significantly shorter than the duration of respiratory symptoms (P < 0.01). [2]

We found 7 studies reported critical cases. I2 (inconsistency) was 76.6%, Q test for heterogeneity (p=0.0003), so randomeffects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of critical cases=7.7% (p < 0.05). Which came in agreement with Lala et al., [17] Mantovani et al., [14] Espinosa et al. [3]

Lala et al. reported that, of 2736 COVID-19 patients included in our study 18.5% died, 41.4% were discharged, and 40.1% remained hospitalized. The median length of stay was 5.75 days. In a Cox proportional hazards regression model, increased age, increased BMI, and higher illness severity were associated with increased risk of death. [17]

Mantovani et al. reported that, 2855 (mainly Chinese) children and/o adolescents (mean age 6.9 years; 50.3% males) with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 disease by nasopharyngeal swabs. Eighteen of the eligible studies provided data on major adverse events, whereas one described only the severity of the disease. Children and adolescents presented mild symptoms in 72 cases, whereas only 4% of patients were considered critical. [14]

Espinosa et al. reported that in the 39 studies used to calculate the pooled prevalence of comorbidities, 89,238 patients affected by COVID-19 were analyzed; 11,341 (12.7%) presented one or more comorbidities, 2,172 (2.4%) were admitted to the ICU, and 3,532 (4%) patients died. [3]

Concerning the secondary outcome measures, we found 6 studies that reported CT involvement. I2 (inconsistency) was 90% with a highly significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), so random-effects model was carried out; with a pooled prevalence of CT involvement=41.6% (p < 0.05), which came in agreement with Gavriatopoulou et al. [4]

Gavriatopoulou et al. reported that findings on chest radiograph imaging are not disease-specific and usually include groundglass opacities with bilateral, peripheral, or lower lung with or without consolidation. CT is highly sensitive, but couldn’t rule out the diagnosis. CT findings are categorized into typical, indeterminate, or atypical for COVID-19 demonstrating that specificity is low even for CT [4].

Conclusion

To conclude, COVID-19 disease cause different manifestations in children such as fever and respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnea, organizing pneumonia and decreased pulmonary function.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All the listed authors contributed significantly to the conception and design of study, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript, to justify authorship.

REFERENCES

- Badawi A, Ryoo SG. Prevalence of comorbidities in the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;49:129-133.

- Cholankeril G, Podboy A, Aivaliotis VI, Tarlow B, Pham EA, Spencer SP, et al. High Prevalence of Concurrent Gastrointestinal Manifestations in Patients With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: Early Experience From California. Gastroenterol. 2020;159:775-777.

- Espinosa OA, Zanetti A dos S, Antunes EF, Longhi FG, Matos TA de, Battaglini PF. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients and mortality cases affected by SARS-CoV2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2020;62.

- Gavriatopoulou M, Korompoki E, Fotiou D, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Psaltopoulou T, Kastritis E, et al. Organ-specific manifestations of COVID-19 infection. Clin Exp Med. 2020:1-14.

- Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche P, Ioannidis J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions. Bmj 2009;339.

- Covid CDC, COVID C, COVID C, Bialek S, Gierke R, Hughes M, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children United States, February 12–April 2, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:422.

- Derespina KR, Kaushik S, Plichta A, Conway Jr EE, Bercow A, Choi J, et al. Clinical Manifestations and Outcomes of Critically Ill Children and Adolescents with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in New York City. J Pediatr. 2020;226:55-63.

- Feng K, Yun YX, Wang XF, Yang GD, Zheng YJ, Lin CM, et al. Analysis of CT features of 15 children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:E007-E007.

- Mamishi S, Heydari H, Aziz-Ahari A, Shokrollahi MR, Pourakbari B, Mahmoudi S, et al. Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in children in Iran: atypical CT manifestations and mortality risk of severe COVID-19 infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020.

- Mehta N, Kalra A, Nowacki AS. Original: Association of Use of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and 2020.

- Tagarro A, Epalza C, Santos M, Sanz-Santaeufemia FJ, Otheo E, Moraleda C, et al. Screening and severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children in Madrid, Spain. JAMA Pediatr. 2020.

- Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, Ahn D, Sen AI, Fischer A, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children’s hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:e202430-e202430.

- Xia W, Shao J, Guo Y, Peng X, Li Z, Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: Different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:1169-1174.

- Mantovani A, Pernigo M, Bergamini C, Bonapace S, Lipari P, Pichiri I, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with early left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 2015;10.

- Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu Y-J, Mao Y-P, Ye R-X, Wang Q-Z, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:1-12.

- Lang M, Som A, Carey D, Reid N, Mendoza DP, Flores EJ, et al. Pulmonary vascular manifestations of COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2:e200277.

- Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, Russak AJ, Paranjpe I, Richter F, et al. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:533-546.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.