Prosthodontic Approach to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Annapurna Kannan

Dr. Annapurna Kannan, SRM Dental College, Barathi Salai, Ramapuram, Chennai - 600 089, Tamil Nadu, India.

E-mail: annapurnakannan@gmail.com

Abstract

Sleep disordered breathing represents a continuum, ranging from simple snoring sans sleepiness, upper‑airway resistance syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) syndrome, to hypercapnic respiratory failure. Fifty seven articles formed the initial database and a final total of 50 articles were selected to form this review report. Four months were spent on the collection and retrieval of the articles. Articles were selected based on accuracy and evidence in the scientific literature. Oral appliances (OAs) are indicated for use in patients with mild to moderate OSA who prefer them to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, or for those who do not respond to, are not appropriate candidates for, or for those who have failed treatment attempts with CPAP. OAs protrude the mandible and hold it in a forward and downward position. As a consequence, the upper airway enlarges antero‑posteriorly and laterally, improving its stability. Although OA are effective in some patients with OSA, they are not universally suitable. Compliance with OAs depends mainly on the balance between the perception of benefit and the side effects. In conclusion, marked variability is illustrated in the individual response to OA therapy and hence the treatment outcome is subjective.

Keywords

Mandibular advancement, Oral appliances, Sleep apnea

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a sleep disordered breathing disease involving repeated obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. The occlusion of the upper airway is caused by sleep-induced physiologic change in muscle activity superimposed with various structural defects of upper airway, sleeping in supine position, upper airway edema caused by smoking, hypothyroidism, acromegaly and nasal obstruction.[1-10] Various terms are used to describe OSA [Table 1]. OSA is a serious systemic disorder, when untreated may cause hypertension, severe hypoxemia, ventricular and supra-ventricular cardiac arrhythmias.[11-15]

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| ApneaHypopnea | Cessation of airflow at least 10 s>50% decrease in airflow amplitude ofat least 10 s; or<50% decrease in airflowamplitude associated with either an arousalor oxygen desaturation of>3% |

| Respiratory effectrelated arousal | An event characterized by increasingrespiratory effort for>10 s, leading to anarousal from sleep but which does not fulfillthe criteria for a hypopnea or apnea |

| Apnea/hypopneaindex | No. of apnea+hypopnea episodes per hourof sleep |

| Respiratorydisturbance index | No. of apnea+hypopneaepisodes+arousals per hour of sleep |

| Oxygendesaturation index | No. of times per hour of sleep that theblood’s oxygen level drops by 3% or morefrom the baseline |

OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea

Table 1: Terms used to describe OSA

Methods of Literature Search

The Google search engine was used to search for keywords such as OSA, oral appliances (OA), and snoring appliances. Fifty seven articles formed the initial database and a final total of 50 articles were selected to form this review report. Four months were spent on the collection and retrieval of the articles.

Method of Article Selection

Topic selection

↓

Selection of keywords

↓

Collection of articles

↓

Evaluation of articles based on its accuracy and evidence in the scientific literature

↓

Review and gradation of articles which were within the purview of the chosen topic

↓

Delineation of the results and conclusion of the articles

↓

Writing of the review report

Summary of Key Articles

| Article | Author | Number of subjects | Article type | Study design | Key message |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A randomized crossover | Kathleen | 27 | Original | Randomized, | It was concluded that OA is effective in the |

| study of an oral appliance | Ferguson, et al. | article | prospective, | treatment of patients with mild-moderate OSA | |

| versus nasal-continuous | cross-over | and is associated with fewer side-effects and | |||

| positive airway | study | greater patient satisfaction than N-CPAP | |||

| pressure (N-CPAP) | |||||

| in the treatment of | |||||

| mild-moderate obstructive | |||||

| sleep apnea (Chest. | |||||

| 1996;109:1269-75) | |||||

| Comparison of three oral | Gabriele | 8 | Original | Prospective, | Mandibular advancement device is an effective |

| appliances for treatment of | Barthlen, et al. | article | cross-over | treatment alternative in some patients with | |

| severe obstructive sleep | study | severe OSA. In comparison, the tongue | |||

| apnea syndrome (Sleep | retaining device and the soft palate lift do not | ||||

| Medicine. 2000;1:299-305) | achieve satisfactory results | ||||

| The efficacy of oral | Richard | 24 | Original | Longitudinal | Patients who failed |

| appliances in the | Millman, et al. | article | study | uvulopalato-pharyngoplasty (UPPP) for OSA | |

| treatment of persistent | had an adjustable OA (Herbst) made to treat | ||||

| sleep apnea after | the persistent apnea. The responders had | ||||

| uvulopalato-pharyngoplasty | complete resolution of subjective symptoms | ||||

| (Chest. 1998;113:992-96) | of daytime sleepiness with the appliance An | ||||

| adjustable oral appliance was shown to be an | |||||

| effective mode of therapy to control OSA after | |||||

| an unsuccessful UPPP | |||||

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Seung Hyun | 14 | Original | Cross- | The oral appliance appears to enlarge the |

| patients with the oral | Kyung, et al. | article | sectional | pharynx to a greater degree in the lateral than | |

| appliance experience | study | in the sagittal plane at the retropalatal and | |||

| pharyngeal size and | retroglossal levels of the pharynx, suggesting | ||||

| shape changes in three | a mechanism for the effectiveness of oral | ||||

| dimensions (Angle Orthod. | appliances that protrude the mandible | ||||

| 2004;75:15-22) | |||||

| A randomized, controlled | Konrad Bloch, | 24 | Original | Controlled, | OSA-Herbst and OSA-Monobloc are |

| crossover trial of two | et al. | article | Cross-over | effective therapeutic devices for sleep apnea. | |

| oral appliances for sleep | study | OSA-Monobloc relieved symptoms to a greater | |||

| apnea treatment (Am. J. | extent than the OSA-Herbst, and was preferred | ||||

| Respir. Crit. Care Med. | by majority of patients on the basis of its simple | ||||

| 2000;162:246-251) | application | ||||

| An individually adjustable | Winfried | 20 | Original | Randomized, | In patients with mild-to-moderate OSA, CPAP |

| oral appliance versus | Randerath, et al. | article | cross-over | is more effective as a long term treatment | |

| continuous positive | study | modality. Despite its effectiveness in the | |||

| airway pressure in | treatment of the OSA syndrome, N-CPAP is | ||||

| mild-to-moderate | not fully accepted by all patients. Therefore, | ||||

| obstructive sleep apnea | attempts have been made to employ OAs | ||||

| syndrome (Chest | alternatively | ||||

| 2002;122 (2):569-575) | |||||

| Effect of oral appliance | Andrew Ng | 10 | Original | Prospective, | This article examined the effect of a Mandibular |

| therapy on upper airway | article | cross- | Advancement Splint (MAS) on upper airway | ||

| collapsibility in obstructive | sectional | collapsibility during sleep in OSA. Significant | |||

| sleep apnea (Am. J. | study | improvements with MAS therapy were seen | |||

| Respir. Crit. Care Med. | in the apnea/hypopnea index indicating that | ||||

| 2003;168 (2):238-241) | MAS therapy is associated with improved upper | ||||

| airway collapsibility during sleep. The mediators | |||||

| of this effect remain to be determined | |||||

| Practice parameters | Clete Kushida, | Review | This article is an update of the previously | ||

| for the treatment of | et al. | report | published recommendations regarding the use | ||

| snoring and obstructive | of oral appliances in the treatment of snoring | ||||

| sleep apnea with oral | and OSA. OAs are indicated for use in patients | ||||

| appliances: An update | with mild to moderate OSA who prefer them to | ||||

| for 2005 (Sleep. 2006;29 | CPAP therapy, or who do not respond to, are not | ||||

| (2):240-243) | appropriate candidates for, or who fail treatment | ||||

| attempts with CPAP. Until there is higher quality | |||||

| evidence to suggest efficacy, CPAP is indicated | |||||

| whenever possible for patients with severe OSA | |||||

| before considering OAs |

CPAP: Continuous positive airway pressure, OA: Oral appliance, OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea, UPPP: Uvulopalato-pharyngoplasty, MAS: Mandibular advancement splint

Treatment Options for OSA

There are various surgical and non-surgical treatment modalities currently available for OSA [16,17] [Table 2]. The most commonly followed medical intervention includes nasal continuous positive airway pressure (N-CPAP), which was introduced by Sullivan et al. (1981) as a pneumatic splint to prevent collapse of the pharyngeal airway and has become the first choice therapy for OSA.[18-23] OSA symptoms, such as snoring and daytime somnolescence, are well known. Snoring appears to affect 35-40% of adults and is related to OSA. The treatment options for OSA include positive airway pressure devices, OAs, medications (such as nasal steroids and decongestants) and surgical techniques such as, tracheostomy, nasal surgery (septoplasty, turbinectomy, polypectomy), uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) and laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty. The recent approaches include electrical pacing, radio-frequency ablation and rapid maxillary expansion.[24-32] OA therapy has proved effective over the past 10 years in treating patients with OSA, by reducing the apnea and hypopnea index (AHI), improving oxygen saturation during sleep, reducing snoring and more recently, reducing arterial pressure. The efficacy of an OA depends on its retention and the amount of mandibular protrusion.

| Treatment type | Measure used | |

|---|---|---|

| ConservativeMedical | Lose weight, sleep in lateral position, avoid alcoholUse nasal continuous airway pressure, auto-continuous positive airway pressure, bilevelpositive airway pressureUse oral appliancesGive medicationTreat associated diseases, e.g., hypothyroidism,acromegaly, allergic rhinitis | |

| Surgical | TracheostomyNasal procedure, e.g., turbinectomy, polypectomy,septoplastyUvulopalatopharyngoplastyLaser assisted uvulopalatoplastyMaxilla-mandibular advancement | |

| Experimental | Pharyngeal pacingRadio-frequency ablationRapid maxillary expansion | |

OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea

Table 2: Treatment modalities for OSA

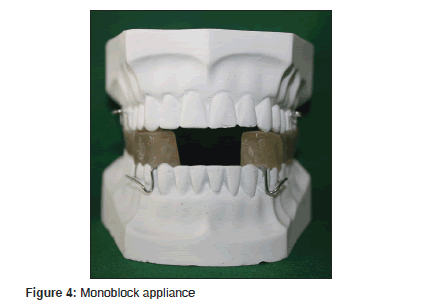

Historical Perspective

George Cattlin was the first person to relate the influence of sleep quality on daytime function. He stated that native North American Indians were healthier than their immigrant counterparts and attributed it to the habit of breathing through their nose rather than the mouth.[33] Following his work; there were many patented devices to promote nasal breathing. However, documented clinical work began in 1903, when Pierre Robin first described his device “monoblock”, for the treatment of glossoptosis.[34] Fifty years later, Cartwright and Samelson (1982) described the tongue retaining device (TRD).[35]

Types of Appliances

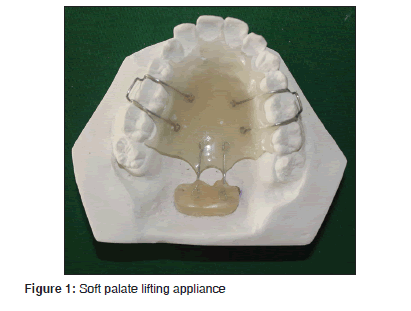

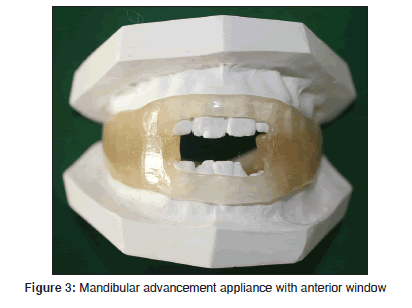

The OAs used for OSA are still under research and growing [Table 3]. The three general groups of appliances are soft palate lifters (SPL) [Figure 1], TRD [Figure 2] and mandibular advancement appliance (MAA) [Figures 3 and 4]. The OA most commonly in use today is MAA. It protrudes the mandible forward, thus preventing or minimizing upper airway collapse. The amount of protrusion can be either fixed or variable.

| The equalizer | Japanese jumper | Es mark |

|---|---|---|

| The stencer | PM positioned | TPE |

| Klearway | Tongue locking appliance | SnoreEx |

| NAPA | Adjustable soft palate lifter | HAP |

| TAP | Z-training appliance | Tossi |

| TOPS | Snore no more | Snore guard |

| SNOAR | Elastomeric | Silent night |

| Herbst | SUAD | Therasnore |

NAPA: Nocturnal airway patency appliance,TAP: Thornton adjustable positioner , SNOAR: Sleep and Nocturnal Apnea Reducer

Table 3: Examples of oral appliances

Mechanism of Action of OAs

Upper airway obstruction can occur between the nasopharynx and the larynx. The most common sites of obstruction are behind the base of the tongue (retroglossal) and behind to the soft palate (retroplalatal). Neuromuscular decontrol is speculated as the cause for airway obstruction. The pathological repetitive narrowing (or complete obstruction) of the upper airway is due to the combination of abnormal anatomy and the abnormal physiology.[36,37] Battagel et al. and Ng et al. conducted various studies to determine the selection criteria for patients to receive OAs. They concluded that oropharyngeal collapse, rather than the velopharyngeal collapse, was predictive of a more beneficial response to OAs.[38,39] According to Banabilh et al., 96% increase in the area associated with the downward displacement of the hyoid bone was detected in patients with OSA.[40]

The presumed mechanism of action for OAs is that anatomical changes in the oropharynx, produced by MAA, result in an alteration of the intricate relationships between different muscle groups controlling the upper airway caliber.[41] There is currently no reliable method for the selection criteria and for the treatment outcome.

Clinical Trials

The clinical studies on OAs started with Cartwright and Samelson (1982). The most commonly used criterion in clinical studies is the nocturnal monitoring of respiration with and without OAs. In some investigations, formal in-hospital polysomnography was performed, while in others, only at-home monitoring of oxygen saturation, oxygen desaturation index and apnea index were recorded. In recent investigations AHI, or respiratory disturbance index were used.[42] The first step in analyzing the results of individual investigations is to decide on which outcome variable to analyze. The following four variables are an apparent choice for OSA: (1) Baseline index for respiration (AHIbase), (2) “With appliance” index of respiration, (3) Success rate defined as the reduction of AHIbase to a value less than the defining value for sleep apnea and response rate defined as the reduction of AHbase by >50% while still remaining higher than the defining value for OSA. Bloch et al. (2000) compared the effectiveness and side-effects of a novel, single piece MAA device (OSA-Monobloc) with a two piece, lateral Herbst attatchments (OSA-Herbst) appliance and concluded that OSA-Monobloc relieved symptoms to a greater extent than OSA-Herbst.[43] Ferguson et al. (1997) conducted a prospective cross-over study to compare efficacy, side-effects, patient compliance and preference between MAA and N-CPAP in patients with symptomatic mild to moderate OSA and concluded that MAA is a better treatment option with greater patient satisfaction.[44] Gale et al. (2000) evaluated the effect of a MAA on minimum pharyngeal cross-sectional area (MPCSA) in 32 conscious, supine subjects with OSA and concluded that the MAA significantly increased MPCSA.[45] Barthlen et al. (2000) compared three different OAs: A MAA (snoreguard), a TRD and a SPL appliance for the treatment of severe OSA syndrome and stated that MAA is an effective treatment alternative in some patients.[46] Kyung et al. (2005) studied the pharyngeal size and shape difference between pre- and post-trials of MAAs, using cine computerized tomography and revealed that the MAA appeared to enlarge the pharynx to a greater degree in the lateral than in the sagittal plane at the retropalatal and the retroglossal levels of the pharynx, suggesting a mechanism for the effectiveness of the OA.[47] Almeida et al. studied the long-term sequelae of OA therapy and found that after a mean of 7.4 years, OAs induce clinically relevant changes in the dental arch and the occlusion.[48] MAA devices may have no effect on obstruction associated with cranial base morphology, nasal obstruction or retropalatal obstruction. Furthermore, the application of MAAs may not be a good choice for subjects with Class III malocclusion where the jaw is already protruded. A possible alternative to MAAs might be the use of a maxillary OA. Maxillary OAs putatively induce renewed midfacial development and provide an alternative approach to managing OSA, by permitting non-surgical remodeling of the upper airway.[49,50]

OAs vs Other Treatment

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) prevails as the “gold standard” of treatment for OSA. Hence, any other newer approach has to be compared against it. There are almost seven randomized controlled studies that compared OAs with CPAP. In all studies, CPAP showed better results than OAs in bringing the AHI <10. Smith and Stradling substituted OA for CPAP for a month and stated that OA produced similar reduction in hypopneas (number of times/hour of sleep that the blood’s oxygen level drops by 3% or more from the baseline) from 29 to 4.[41] Since 1988, there are several studies comparing the efficacy of different OAs. The summary of the studies shows that the efficiency of each OA depends on the design and the degree of MAA.

There were several clinical studies that compared OA with UPPP and demonstrated the superiority of OA with 78% reduction in OSA in OA group and 51% in the UPPP group.

Conclusion

Compliance with OA depends mainly on the balance between the perception of benefit and the side effects. OAs used till date constitute a relatively heterogeneous group of devices for the treatment of OSA and non-apneic snoring, which accounts for variability in benefits and side-effects. To conclude from the vast reviews and in compliance with the recent review by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, marked variability is illustrated in the individual response to OA therapy and hence the treatment outcome is subjective.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. B. Muthukumar, Professor and HOD, Department of Prosthodontics, SRM Dental College, Ramapuram, Chennai for providing his support and allowing to present ‘Prosthodontic approach to treat OSA’ as a table clinic in the 13th Student Clinician Program held in India.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Mezon BJ, West P, MaClean JP, Kryger MH. Sleep apnea in acromegaly. Am J Med 1980;69:615-8.

- Perks WH, Horrocks PM, Cooper RA, Bradbury S, Allen A, Baldock N, et al. Sleep apnoea in acromegaly. Br Med J 1980;280:894-7.

- Imes NK, Orr WC, Smith RO, Rogers RM. Retrognathia and sleep apnea. A life-threatening condition masquerading as narcolepsy. JAMA 1977;237:1596-7.

- Bear SE, Priest JH. Sleep apnea syndrome: Correction with surgical advancement of the mandible. J Oral Surg 1980;38:543-9.

- Kuo PC, West RA, Bloomquist DS, McNeil RW. The effect of mandibular osteotomy in three patients with hypersomnia sleep apnea. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1979;48:385-92.

- Johnston C, Taussig LM, Koopmann C, Smith P, Bjelland J. Obstructive sleep apnea in Treacher-Collins syndrome. Cleft Palate J 1981;18:39-44.

- Afzelius LE, Elmqvist D, Laurin S, Risberg AM, Aberg M. Sleep apnea syndrome caused by acromegalia and the treatment with a reduction plasty of the tongue. Case report. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 1982;44:142-5.

- Cartwright R, Ristanovic R, Diaz F, Caldarelli D, Alder G. A comparative study of treatments for positional sleep apnea. Sleep 1991;14:546-52.

- Wetter DW, Young TB, Bidwell TR, Badr MS, Palta M. Smoking as a risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:2219-24.

- Browman CP, Sampson MG, Yolles SF, Gujavarty KS, Weiler SJ, Walsleben JA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and body weight. Chest 1984;85:435-8.

- Remmers JE, deGroot WJ, Sauerland EK, Anch AM. Pathogenesis of upper airway occlusion during sleep. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1978;44:931-8.

- Gastaut H, Tassinari CA, Duron B. Polygraphic study of the episodic diurnal and nocturnal (hypnic and respiratory) manifestations of the Pickwick syndrome. Brain Res 1966;1:167-86.

- Gastaut H, Duron B, Tassinari CA, Lyagoubi S, Saier J. Mechanism of the respiratory pauses accompanying slumber in the Pickwickian syndrome. Act Nerv Super (Praha) 1969;11:2095.

- Strohl KP, Saunders NA, Sullivan CE. Sleep apnea syndromes. In: Saunders NA, Sullivan CE, editors. Sleep and Breathing. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1984. p. 365-402.

- Imaizumi T. Arrhythmias in sleep apnea. Am Heart J 1980;100:513-6.

- Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic azbnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1981;89:923-34.

- deBerry-Borowiecki B, Kukwa AA, Blanks RH. Indications for palatopharyngoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol 1985;111:659-63.

- Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet 1981;1:862-5.

- Engleman HM, Martin SE, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on daytime function in sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Lancet 1994;343:572-5.

- Engleman HM, Martin SE, Kingshott RN, Mackay TW, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Randomised placebo controlled trial of daytime function after continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax 1998;53:341-5.

- Engleman HM, Martin SE, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Effect of CPAP therapy on daytime function in patients with mild sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax 1997;52:114-9.

- Engleman HM, Kingshott RN, Wraith PK, Mackay TW, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial of continuous positive airway pressure for mild sleep Apnea/Hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:461-7.

- Jenkinson C, Davies RJ, Mullins R, Stradling JR. Comparison of therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: A randomised prospective parallel trial. Lancet 1999;353:2100-5.

- Ferguson KA, Love LL, Ryan CF. Effect of mandibular and tongue protrusion on upper airway size during wakefulness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1748-54.

- Gotsopoulos H, Chen C, Qian J, Cistulli PA. Oral appliance therapy improves symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:743-8.

- Hans MG, Nelson S, Luks VG, Lorkovich P, Baek SJ. Comparison of two dental devices for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1997;111:562-70.

- Mehta A, Qian J, Petocz P, Darendeliler MA, Cistulli PA. A randomized, controlled study of a mandibular advancement splint for obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1457-61.

- Johnston CD, Gleadhill IC, Cinnamond MJ, Peden WM. Oral appliances for the management of severe snoring: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod 2001;23:127-34.

- Randerath WJ, Heise M, Hinz R, Ruehle KH. An individually adjustable oral appliance vs continuous positive airway pressure in mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 2002;122:569-75.

- Tan YK, L’Estrange PR, Luo YM, Smith C, Grant HR, Simonds AK, et al. Mandibular advancement splints and continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: A randomized cross-over trial. Eur J Orthod 2002;24:239-49.

- Gotsopoulos H, Kelly JJ, Cistulli PA. Oral appliance therapy reduces blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized, controlled trial. Sleep 2004;27:934-41.

- Otsuka R, Ribeiro de Almeida F, Lowe AA, Linden W, Ryan F. The effect of oral appliance therapy on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2006;10:29-36.

- Catlin G. The Breath of Life. New York: Wiley; 1872.

- Robin P. Practical demonstration on the construction and commissioning of a new unit enbouche recovery. Journal of Stomatology. 1902 9:561-90.

- Cartwright RD, Samelson CF. The effects of a nonsurgical treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. The tongue-retaining device. JAMA 1982;248:705-9.

- Schwab RJ. Pro: Sleep apnea is an anatomic disorder. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:270-1; 273.

- Strohl KP. Con: Sleep apnea is not an anatomic disorder. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:271-2.

- Battagel JM, Johal A, Kotecha BT. Sleep nasendoscopy as a predictor of treatment success in snorers using mandibular advancement splints. J Laryngol Otol 2005;119:106-12.

- Ng AT, Gotsopoulos H, Qian J, Cistulli PA. Effect of oral appliance therapy on upper airway collapsibility in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:238-41.

- Banabilh SM, Suzina AH, Dinsuhaimi S, Singh GD. Cranial base and airway morphology in adult malays with obstructive sleep apnoea. Aust Orthod J 2007;23:89-95.

- Petit FX, Pépin JL, Bettega G, Sadek H, Raphaël B, Lévy P. Mandibular advancement devices: Rate of contraindications in 100 consecutive obstructive sleep apnea patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:274-8.

- Hoffstein V. Review of oral appliances for treatment of sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath 2007;11:1-22.

- Bloch KE, Iseli A, Zhang JN, Xie X, Kaplan V, Stoeckli PW, et al. A randomized, controlled crossover trial of two oral appliances for sleep apnea treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:246-51.

- Ferguson KA, Ono T, Lowe AA, al-Majed S, Love LL, Fleetham JA. A short-term controlled trial of an adjustable oral appliance for the treatment of mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 1997;52:362-8.

- Gale DJ, Sawyer RH, Woodcock A, Stone P, Thompson R, O’Brien K. Do oral appliances enlarge the airway in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea? A prospective computerized tomographic study. Eur J Orthod 2000;22:159-68.

- Barthlen GM, Brown LK, Wiland MR, Sadeh JS, Patwari J, Zimmerman M. Comparison of three oral appliances for treatment of severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med 2000;1:299-305.

- Kyung SH, Park YC, Pae EK. Obstructive sleep apnea patients with the oral appliance experience pharyngeal size and shape changes in three dimensions. Angle Orthod 2005;75:15-22.

- Almeida FR, Lowe AA, Otsuka R, Fastlicht S, Farbood M, Tsuiki S. Long-term sequellae of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea patients: Part 2. Study-model analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129:205-13.

- Singh GD, Callister JD. Effect of a maxillary appliance in an adult with obstructive sleep apnea: A case report. Cranio 2013;31:171-5.

- Singh GD, Wendling S, Chandrashekhar R. Midfacial development in adult obstructive sleep apnea. Dent Today 2011;30:124-7.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.