The Social Determinants of Depression among Adolescents in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Scoping Review Protocol

2 Department of Medical and Health Science, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

3 Department of Psychology, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda

4 Department of Sociology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

Received: 08-Oct-2024, Manuscript No. amhsr-24-150010; Editor assigned: 10-Oct-2024, Pre QC No. amhsr-24-150010 (PQ); Reviewed: 24-Oct-2024 QC No. amhsr-24-150010; Revised: 31-Oct-2024, Manuscript No. amhsr-24-150010 (R); Published: 07-Nov-2024

Citation: Wubshet I. The Social Determinants of Depression among Adolescents in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Scoping Review Protocol. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2024;1063-1067.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Adolescence is an important and stressful period characterized by rapid biological, psychological and social changes. Early signs of depression often emerge during early adolescence. Apart from biological and psychological factors, the interaction among different social factors in the family, school and neighborhood plays a significant role in determining depression among adolescents. Although depression is highly prevalent in low and middle income countries, there is a shortage of comprehensive scoping reviews that examine the social factors and their relationships.

Objective: The purpose of this review is to gain an understanding of the social determinants of adolescent depression in family, school and neighborhood settings.

Method and analysis: This protocol will adhere to framework for conducting scoping reviews, carefully detailing each stage of the process. Firstly, we will use predetermined keywords to systematically search across eight electronic resources. Two reviewers will then carefully assess the titles and abstracts of retrieved studies. Only those deemed pertinent will proceed to full-text screening. Studies will be selected according to established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The review team will conduct the data extraction procedure on its own. Finally, the included studies will undergo thorough qualitative and quantitative analyses. The results will be presented at conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Keywords

Adolescent depression; Social determinants; Low and middle income countries; Risk factors; Protective factors

Introduction

Good mental wellbeing relies on healthy psychological, biological and social environments. Distortions in these environments can detrimentally affect mental health, contributing to various mental illnesses. Globally, approximately 970 million individuals suffer from mental health disorders, with depression ranking the third leading burden of disease worldwide [1]. In between 2005 and 2015, there was an 18.4% increase in the number of persons living with depression, reaching 300 million in 2018 [1,2]. By 2030, depression is expected to rank second in terms of causes of disability, excluding the 25% rise linked to COVID-19 [3,4]. Depression affects the healthy functioning of a person [5]. It has physiological and socio-emotional manifestations such as loss of appetite, tiredness, low mood, sadness, a feeling of guilt, feelings of inferiority and personal and social life displeasure, which affect anyone regardless of gender and age [6-9]. When these symptoms persist, a person loses interest in activities they usually like and becomes unable to perform everyday tasks [10].

Early depressive signs begin to manifest at a younger age [11- 14]. WHO defines adolescence as the life span from 10 to 19 years, which is a transitional stage from childhood to adulthood that results in physical, psycho-emotional and social changes [15- 18]. This age group is considered "critical" and this is primarily because the rapid development observed during adolescence exposes them to many risky behaviors that affect their current and future lives [19]. Adolescence is a period of uncertainty, vulnerability, risk, taking responsibility and problems with relationships [16]. A World Health Organization (WHO) report disclosed that depression is a significant mental disorder among adolescents, accounting for 16% of the mental disorder burden and leading to 40%-60% premature mortality. 34% of adolescents are vulnerable to depression, with the rate surpassing 18 years-25 years, leading to one million avoidable adolescent deaths. 8% of adolescents who have experienced a mental condition in their lifetime report having depression. These adolescents reside in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs), home to around ninety percent of the 1.2 billion adolescents worldwide. This pattern is remarkably noticeable in African and Asian nations, where communicable diseases are more prevalent. Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa have a 26.9% prevalence of depression.

Adolescent depression is no longer an individual issue. Rather, it is now a social pathology that causes both immediate and longterm societal difficulties and crises. Adolescents participate in a range of social interactions and engage in various social networks, which can significantly impact their mental well-being, either positively or negatively. Therefore, attempting to view adolescents independently of these social contexts is similar to separating the soul from the body, rendering both devoid of life. Thus, it is important to examine the significant external social factors that extend beyond the examination of an individual's internal bio-psychological factors. While etiologically based scoping reviews on adolescent depression, particularly focusing on social factors, remain limited, the research team is deeply concerned by the absence of previous studies addressing low- and middle-income countries. Conversely, emerging research highlights a troubling surge in adolescent depression within these countries, imposing a mounting public health burden. Therefore, understanding the complexities of external socio-structural factors within family, school and community settings, which wield significant influence over the outcomes of adolescent depressive symptoms, becomes imperative for a comprehensive understanding of the issue and for effective service delivery. Thus, the purpose of this scoping review protocol is to provide a guide on how to undertake a scoping review of the social contexts that lead to and prevent adolescent depression in low and middle-income countries.

Literature Review

The primary goal of this protocol is to detail the approach for carrying out a scoping review on the social factors that affect depression in adolescents living in low and middle income countries [20-30]. It will follow the structure of a scoping review which includes the following steps: Identifying the research question, searching for relevant studies, selecting studies, mapping out the data, summarizing and reporting the results and including expert consultation [31]. Any modifications or improvements made throughout the review will be integrated into the final scoping review paper.

Identifying the research question

Drawing from a preliminary exploration of the literature, the research questions have been formulated. The primary research question of this review is to identify the major social risk and protective factors contributing to the development of depression among adolescents (aged 10 years-18 years) in low and middle income countries. Following the primary research question, the specific research objectives are outlined as follows:

• What are the differences between boys and girls, as well as different socio-economic groups, in terms of depressive symptoms?

• In what ways do family contexts contribute to or prevent depressive symptoms among adolescents in LMICs?

• How do school environments influence the occurrence or prevention of depressive symptoms among adolescents in LMICs?

• What role do neighborhood contexts play in either reducing or moderating depressive symptoms among adolescents in LMICs?

• How do social factors within family, school and community settings interact to impact adolescent depressive symptoms in LMICs?

Identifying relevant studies

This review will encompass both peer-reviewed studies and gray literature. The electronic databases to be utilized include Google Scholar, PsychInfo (via Ovid), Web of Science, PubMed, Sociological Abstracts (via Proquest) and Embase (via Ovid). Moreover, the reference lists of the included studies will be carefully examined to identify any relevant literature. Search terms will be employed to query all databases for literature published from January, 2010 to December, 2023. Literature written in languages other than English will not be included. The following table outlines the search strategy.

Study selection

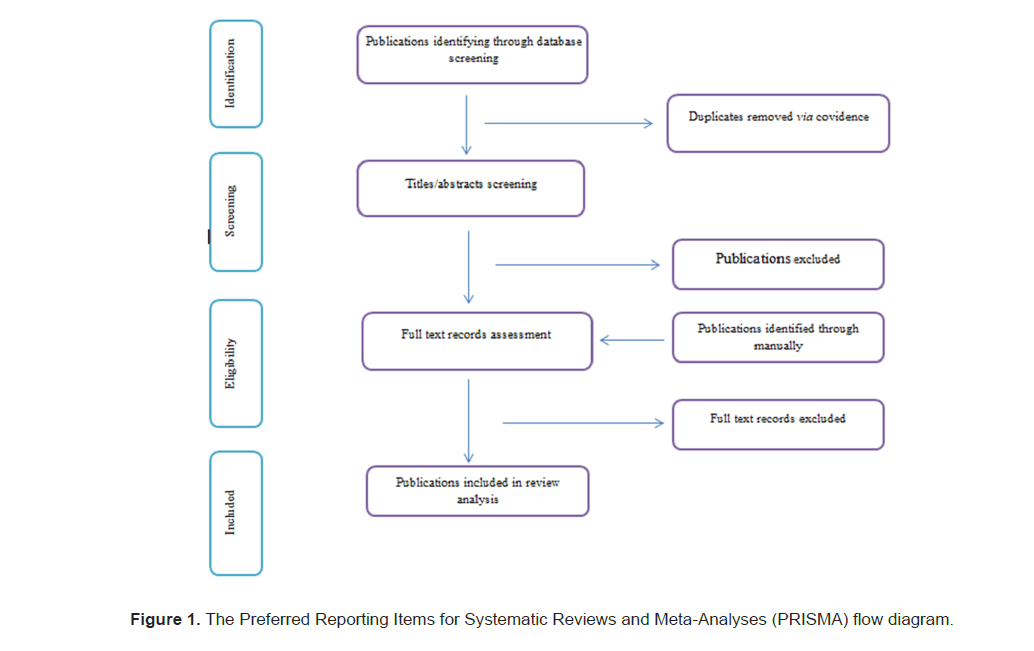

The online scoping review tool covidence will be used to help with the study selection process. Literature obtained from search engines for both peer-reviewed and gray literature will be exported to endnote and subsequently imported to covidence. Upon the removal of duplicate citations, the initial stage of screening will commence, where two reviewers will conduct the title and abstract screening for all studies retrieved by the search strategy. Any conflicts will be resolved by a third screener, who will engage in discussions with the other two screeners to reach an agreement. After removing papers that do not meet the inclusion criteria based on their titles and abstracts, the next step involves carefully assessing the remaining records to establish their eligibility based on the established criteria. In addition to publications identified through refined database searches, those found manually will also be included. A first independent screening of a sample of retrieved records will be carried out by two team members to guarantee consistent application of the eligibility criteria. Records identified as relevant by either reviewer will advance to the full-text review stage. Inter-rater reliability will be assessed using the percentage agreement, targeting a minimum threshold of 80% [32]. The reviewers will examine any differences in eligibility determinations and, if necessary, involve a third-party adjudicator to settle the issues. In cases where a correction to an article has been made after publication, the corrected version will be used. The authors will be notified by email if any information is missing or if further explanation of the data is needed. Records not available electronically will be procured via interlibrary loan through the University of Aberdeen, with a 30 day allowance for receipt (Figure 1).

Study selection

Before commencing the data extraction phase, an extraction table will be crafted to align with the review's objectives and research questions. Subsequently, a trial run of the extraction form will be conducted using a randomly selected sample of full-text records, encompassing five to eight records based on the number of studies included. Two reviewers will independently extract key information from the selected studies, meticulously recording their findings in a microsoft excel sheet. In the event of any discrepancies in the data extracted by the two team members, vibrant discussions will ensue. These spirited exchanges will continue until a harmonious consensus is reached, or the melodious input of the third reviewer will be sought for a harmonious resolution (Table 1).

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies including adolescents aged 10-18 years | Studies dealing with people below 10 years old and adult people (above the age of 18) |

| Studies on adolescents living in the community (such as with their families, relatives and so on) | Studies that only include adolescents in residential care, hospital foster care or in prison |

| Studies exhaustively or mainly on depression | Studies dealing with other mental and psycho-emotional health issues |

| Focusing on one or more social factors for adolescent depression | Studies focusing only on measuring prevalence and associated factors (the factors that are not exhaustively examined rather than simply showing the statistical significance) |

| Being a universal sample | Studies focused on specific medical cohorts |

| Natural disaster-related depression (e.g. due to earthquake, flood, etc.) | |

| Empirical studies | Opinion papers, letters to the editor, editorials, or comments |

| Systematic and scoping review | |

| Studies for testing model, theory, approach, platform, intervention, tool | |

| Urban setting | Non-urban and mixed (both urban and rural) setting |

| Studies written in English language | Studies written in other language than English |

Table 1: List of Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Collating, summarizing and reporting the findings

The selected records will be imported into NVivo Version 14, qualitative data analysis software. Two reviewers will independently code a 10% random sample of the records. This initial assessment aims to compute cohen’s kappa coefficient (k), a statistical measure for assessing inter-rater reliability without necessitating discussion. A Cohen’s kappa coefficient exceeding 0.80 indicates a picture of satisfactory reliability, setting the stage for insightful findings. Once consensus is reached, the remaining selected records will be independently coded by each reviewer. To ensure consistency and reliability, regular meetings will be scheduled between the two coders.

These meetings will facilitate the comparison of coding results, the resolution of any coding discrepancies and the review of the codebook's content. Where applicable, quantitative data will be visually represented through diagrams, tables, or other descriptive formats. Concurrently, qualitative findings will be subjected to thematic analysis to identify key themes. In the final phase, the major findings will be reported in alignment with the objectives of this scoping review. Recognizing the inherent flexibility of such reviews, adjustments to the approach and procedures will be made as deemed necessary.

Discussion

Strength and limitations

As far as our understanding extends, this scoping review will be the inaugural attempt to systematically explore, map and pinpoint research gaps, thus facilitating for future research endeavors concerning the social determinants of adolescent depression in LMICs. Moreover, it will furnish policymakers, researchers and healthcare professionals with invaluable insights to craft targeted interventions. Our method is not free from some limitations. It is important to understand that scoping reviews are primarily intended to map the scope and breadth of the literature, not to delve into its specifics, such assessing the findings' validity. Moreover, rather than producing new knowledge, scoping studies aim to describe knowledge gaps in the literature. We will not examine research quality or bias, nor will we systematically assess the evidence's external validity, as is common in systematic reviews. Rather, we will concentrate on summarizing the salient features of the best-available data regarding the ways in which the contexts of the home, school and community either promote or inhibit the development of depressive symptoms.

Ethics and dissemination

Instead of assessing the quality of each study individually, the report will deliver a thorough overview of existing evidence, consolidate findings and present a summary outline. Given that the review relies on publicly accessible publications and materials, ethical approval is not necessary. Following the completion of our review, this information will be disseminated among health administrators, relevant professionals and researchers through publication in high-impact journals and presentation at conferences. Moreover, the gaps identified in the review will be instrumental in informing the principal investigator's dissertation proposal.

Conclusion

The review will specifically target studies published from 2010 to the end of 2023, potentially overlooking older yet pertinent research. Moreover, our inclusion criteria were restricted to English language records, potentially excluding significant non- English publications. The availability and quality of data in the included studies may also place restrictions on the breadth of the review, which could affect the precision and thoroughness of our conclusions. Furthermore, while the study focuses on pertinent depressive symptoms in adolescents, it does not assess how therapies affect depression. As a result, the quality of every contained record was not evaluated using a conventional appraisal instrument. However, in a study by Streit N et al., it was suggested that false conclusions stemming from literature searches can be minimized by utilizing multiple electronic literature databases and reviewing at least 10 records during the process. With this review utilizing six electronic literature databases, we anticipate that our findings will be presented with confidence.

Funding

This research was funded by the NIHR (NIHR133712) using UK international development funding from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government, the Court of the University of Aberdeen, the Board of Directors of the University of Rwanda, the Board of Directors of Addis Ababa University, the Board of Directors of The Sanctuary, or our International Advisory Board.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Adolescents: Health Risks and Solutions. 2018.

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 315 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016; 388(10053):1545-1602.

- Rehm J, Shield KD. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019; 21:1-7.

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide. 2022.

- Petersen AC, Compas BE, Brooks-Gunn J, Stemmler M, Ey S, et al. Depression in adolescence. Am Psychol. 1993; 48(2):155.

- Wang L, Feng Z, Yang G, Yang Y, Wang K, et al. Depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in western China: An epidemiological survey of prevalence and correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2016; 246:267-274.

- Weersing VR, Shamseddeen W, Garber J, Hollon SD, Clarke GN, et al. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: Predictors and moderators of acute effects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; 55(3):219-226.

- Zhu S, Wong PW. What matters for adolescent suicidality: Depressive symptoms or fixed mindsets? Examination of cross‐sectional and longitudinal associations between fixed mindsets and suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2022; 52(5):932-942.

- Schaan B. Social determinants of depression in later life. 2013.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Depression: Let's Talk.2017.

- Abela JR. Depression In Children and Adolescents: Causes, Treatment and Prevention. Handbook of Depression In Children and Adolescents/The Guilford Press. 2008.

- Hankin BL. Adolescent depression: Description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy Behav. 2006; 8(1):102-114.

- Jenness JL, Peverill M, King KM, Hankin BL, McLaughlin KA. Dynamic associations between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing psychopathology in a multiwave longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019; 128(6):596.

- Upashree D, Maraichelvi, K. A. Stress, anxiety and depression among adolescents. Ethno Med. 2020; 14(1-2): 68-74.

[Crossref]

- Alshammari A. S, Piko B. F, & Fitzpatrick K. M. Social support and adolescent mental health and well-being among Jordanian students. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2021; 26(1): 211-223.

- Ibrahim N, Sherina MS, Phang CK, Mukhtar F, Awang H, et al. Prevalence and predictors of depression and suicidal ideation among adolescents attending government secondary schools in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2017; 72(4):221-227.

- Jayanthi P, Thirunavukarasu M, Rajkumar R. Academic stress and depression among adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Indian Pediatr. 2015; 52:217-219.

- Sreekanth P, Poojitha M, Kumar GB, Ugandar RE, Setlem VS, et al. Prevalence and coping strategies of depression, anxiety and stress among high school adolescents: A cross sectional study. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2023; 30(3):721-728.

- Mukangabire P, Moreland P, Kanazayire C, Rutayisire R, Nkurunziza A, et al. Prevalence and factors related to depression among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS, in Gasabo district, Rwanda. Rwanda J Med Health Sci. 2021; 4(1):37-52.

- Hunduma G, Deyessa N, Dessie Y, Geda B, Yadeta TA. High social capital is associated with decreased mental health problem among in-school adolescents in Eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022:503-516.

- Demoze MB, Angaw DA, Mulat H. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among orphan adolescents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Psychiatry J. 2018:5025143.

- De-la-Iglesia M, Olivar JS. Risk factors for depression in children and adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Scientific World Journal. 2015:127853.

- Tirfeneh E, Srahbzu M. Depression and its association with parental neglect among adolescents at governmental high schools of Aksum town, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019: A cross sectional study. Depress Res Treat. 2020:6841390.

- Fröjd SA, Nissinen ES, Pelkonen MU, Marttunen MJ, Koivisto AM, et al. Depression and school performance in middle adolescent boys and girls. J Adolesc. 2008; 31(4):485-498.

- Minichil W, Getinet W, Derajew H, Seid S. Depression and associated factors among primary caregivers of children and adolescents with mental illness in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC psychiatry. 2019; 19:1-9.

- Shefaly S, Esperanza Debby Ng, Wong C. H. J. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022; 61: 287–305.

- Jason M. N, Sejal H, B Jane F, Michele J. H, Sachiyo Y, et al. Research priorities for adolescent health in low-and middle-income countries: A mixed-methods synthesis of two separate exercises. J Glob Health. 2018: 8(1).

- Jörns-Presentati A, Napp AK, Dessauvagie AS, Stein DJ, Jonker D, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents: A systematic review. Plos one. 2021; 16(5):e0251689.

- Muntaner C, Ng E, Vanroelen C, Christ S, Eaton WW. Social Stratification, Social Closure and Social Class as Determinants of Mental Health Disparities. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. 2013:205-227.

- Turner RJ, Turner JB, Hale WB. Social Relationships and Social Support. Sociology of mental health: Selected topics from forty years 1970s-2010s. 2014:1-20.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res. 2005; 8(1):19-32.

- McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012; 22(3):276-282.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.