The Use of Guidelines for Lower Respiratory Tract Infections in Tanzania: A Lesson from Kilimanjaro Clinicians

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Bernard A. Mbwele

Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center, P.O. Box 2236, KCMC, Moshi, Tanzania, or Programme Manager -Reproductive Maternal Newborn Child Health,utrition and WASH, Save the Children, P.O. Box 1267, 2nd Floor, Tiger House, Majestic Cinema/Vuga Street, Zanzibar, Tanzania.

E-mail: benmbwele@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Abstract

Background: Evaluations of the guidelines for the management of Lower Respiratory Tract Infections (LRTI) Sub‑Saharan Africa, particularly in Tanzania is scant. Aim: The aim of the study was to assess the usefulness of the current Tanzanian treatment guideline for the management lower respiratory tract infection. Subjects and Methods: A descriptive cross sectional study in 11 hospitals of different levels in the Kilimanjaro region Data were collected from May 2012 to July 2012 by semi‑structured interview for clinicians using 2 dummy cases for practical assessment. Data were analyzed by STATA v11 (StataCorp, TX, USA). Qualitative narratives from the interviews were translated, transcribed then coded by colors into meaningful themes. Results: A variety of principles for diagnosing and managing LRTI were demonstrated by 53 clinicians of Kilimanjaro. For the awareness, 67.9% (36/53) clinicians knew their responsibility to use Standard Treatment Guideline for managing LRTI. The content derived from Standard Treatment Guideline could be cited by 11.3% of clinicians (6/53) however they all showed concern of gaps in the guideline. Previous training in the management of patients with LRTI was reported by 25.9% (14/53), majority were pulmonary TB related. Correct microorganisms causing different forms of LRTI were mentioned by 11.3% (6/53). Exact cause of Atypical pneumonia and Q fever as an example was stated by 13.0% (7/53) from whom the need of developing the guideline for LRTI was explicitly elaborated. Conclusion: The current guidelines have not been used effectively for the management of LRTI in Tanzania.There is a need to review its content for the current practical use.

Keywords

Atypical pneumonia, Clinicians, Community acquired, Lower respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, Q fever, Quality of health care, Sub‑Saharan Africa, Tanzania

Introduction

Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs), is an array of diseases of pneumonia and atypical pneumonia, which collectively manifest a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among infectious diseases worldwide.[1] LRTIs are responsible for substantial mortality[2] for both children [3] and adults in developing countries.[4]

Microbial causes of pneumonia and atypical pneumonia as part of LRTI are known [5‑10] but Coxiella burnetii causing atypical pneumonia of Q‑fever have recently emerged to be of public importance. Unfortunately, diagnosis of atypical pneumonia in sub‑Saharan Africa,[11] particularly Tanzania, has been quite difficult due to the demand of advanced laboratory infrastructure.[12‑14]

It is important to define the guidelines of LRTI by epidemiology, etiology, and clinical features of pneumonia and atypical pneumonia in developing countries,[15,16] especially sub‑Saharan African countries[17‑23] with an example of Tanzania.[24]

There have been efforts to combat atypical pneumonia like Q‑fever in developed countries[25‑28] while sub‑Saharan Africa is lagging behind.[20,29,30] For example, development of severity indices measured by Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), Urea, Respiratory Rate, Blood Pressure and Age ≥65 (CURB 65), Systolic blood pressure, Multilobar infiltrates, Albumin, Respiratory rate, Tachycardia, Confusion, Oxygen, and PH (SMART‑COP) have rarely involved sub‑Saharan Africa.[31‑34]

The Ministry of Health (Tanzania) has developed the Standard Treatment Guideline for clinical identification of atypical pneumonia in Tanzania.[35] This standard guideline is useful in ruling out tuberculosis (TB) and HIV among patients with LRTI.[36] However, the guidelines do not reveal details in severity and classifications for pneumonia and atypical pneumonia compared to the ones in South Africa[37] and India.[38] So far its physical distribution to end users and training is not well known.

The aim of the study was to assess the clinicians’ awareness and experience of using the guidelines for the management of LRTI.

Subjects and Methods

The study design was a cross-sectional descriptive study using qualitative and quantitative approaches for the diagnosis and management of LRTI.

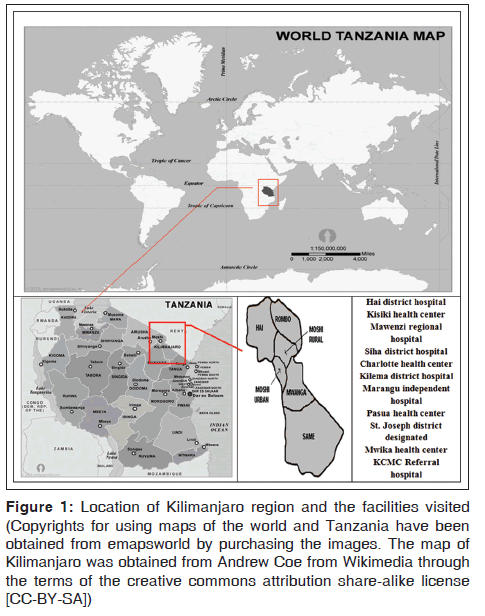

The study was conducted in 11 health facilities of Kilimanajro region North‑East of Tanzania [Figure 1], which has a population of 1,640,087, which was lower than the precensus projection of 1,702,207 according to the 2012 national census. Health facilities were selected purposively to represent three levels of health care (Tertiary Referral Hospital, Regional Referral Hospital, District Hospital and Health Centre) in Kilimanjaro Region. The study population included clinicians working in either internal medicine or the Outpatient Department (OPD) for a year.

Figure 1: Location of Kilimanjaro region and the facilities visited (Copyrights for using maps of the world and Tanzania have been obtained from emapsworld by purchasing the images. The map of Kilimanjaro was obtained from Andrew Coe from Wikimedia through the terms of the creative commons attribution share-alike license [CC-BY-SA])

Ethical approval was obtained from the Local Ethical Committee of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College bearing number 477 following submission of the proposal and the appendices bearing data collection forms and written information and consent forms. After obtaining a letter of introduction from the regional medical officer, the District Medical Officers (DMOs) were asked to give permission for the study. After the DMO gave permission to visit the facilities of the region, medical or clinical officers in charge were asked for consent to interview clinicians and to take pictures that might be used for publication. The officers in charge were then notified when the interviewers would be arriving for data collection, and the clinicians working that day would be informed by the officer in charge that they would be interviewed. All clinicians were informed that data obtained would be analyzed and findings might be published. All clinicians were asked to give written consent before interviews.

Clinicians working in internal medicine for inpatient or outpatient setting and or attended patients with LRTI or unspecified respiratory problems were randomly recruited then consecutively until no more clinicians could be obtained.

Data were collected from May 2012 to July 2012 after checking and correcting the validity and reliability of the questionnaires by the pilot procedure. The pilot of the questionnaire was done at the Zonal Referral Hospital for 5 days in early May 2012. The summary treatment options for LRTI were studied from scientific reports and guidelines.[9,10,35‑38]Interviews were conducted by guided questionnaires using dummy cases to determine medical reasoning; the clinicians were then asked if they ever saw any guideline showing treatment regimens as described in Table 1.

| A: Atypical pneumonia | B: Non severe pneumonia | C: Severe pneumonia | D: Treatment of common resistant organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treat with Doxycycline (O) 200 mg stat then 100 mg daily for 7-10 days In pregnancy, lactation or children <12 year: Alternatively give Erythromycin (O) 500 mg every 6 hours for 7-10 days Asses the patient after two days |

Treat as outpatient Treat with Amoxicillin (O) 250-500 mg, three times a day for 5 days Asses the patient after two days If the patient is not improved: Alternatively give Co-trimoxazole (O) 960 mg (2 tablets of 480 mg) twice daily for 5 days If the patient is still not improved: Treat as atypical pneumonia |

Admit to be managed as inpatient If PO2 by Pulse Oximetry <90% give oxygen Treat for 48 hours with Benzylpenicillin (IV/ IM) 1-3 MU every 6 hours and Gentamicin 4-5 mg/kg/24 hours IV in 3 divided doses or IM in 2 divided doses Monitor 4 hourly If the patient improves: Amoxicillin (O) 250-500 mg 8 hourly for 10-14 days, Gentamicin (IV) 4-5 mg/ kg/24 hours in 3 divided doses for 10-14 days If the compliance to Amoxicilline is doubted: Treat with Benzathine penicillin (IM) 2.4 MU single dose If the patient is not improved: Switch to IM Ceftriaxone 1g for 5 days Consider PICT (HIV-test), then consider AFB-test Discharge home when the patient is able to walk |

If the patient is not responding to the recommended treatment in A, B and C and is AFB-negative Staphylococcal pneumonia more likely: Treat with Cloxacillin (IV) 1-2 mg every 6 hours for 14 days OR Clindamycin (IV/O) 600 mg every 6-8 hours for 14 days Alternatively Ceftazidime (IV/IM) every 8 hours Klebsiella pneumonia more likely: Treat with Chloramphenicol (IV) 500 mg every 6 hours for 10-14 days,± Gentamicin (IV) 4-5 mg/ kg/24 hours in 3 divided doses for 10-14 days Alternatively Ceftazidime (IV/IM) every 8 hours |

Table 1: Summarized treatment pattern from the National Standard Treatment Modality and new suggestions

The interview process involved two dummy cases. The first case was for a 55‑year‑old male, who had cough for 10 days, as well as fever and shortness of breath. The second case was a 68‑year‑old woman, who was presented at the OPD with a history of productive cough for 1 week, a breathing rate of 32breaths/min and a blood pressure of 85/55mmHg. Guided interviews were used to collect the following information from the clinicians: (1) What is the provisional diagnosis? (2) What additional questions they would consider to reach a diagnosis? (3) What do they know about atypical pneumonia, and what is the causative agent for Q‑fever?

The use of open‑ended questions for the detailed narratives allowed investigators to learn insights for the management of patients with LRTI in Kilimanjaro.

Narrative data were entered in Microsoft Access 2007 database. Data were stored in a database with two data sets made by Microsoft Access 2007. Data on records and those from the interviews were analyzed by STATA v10 (StataCorp., TX, USA).

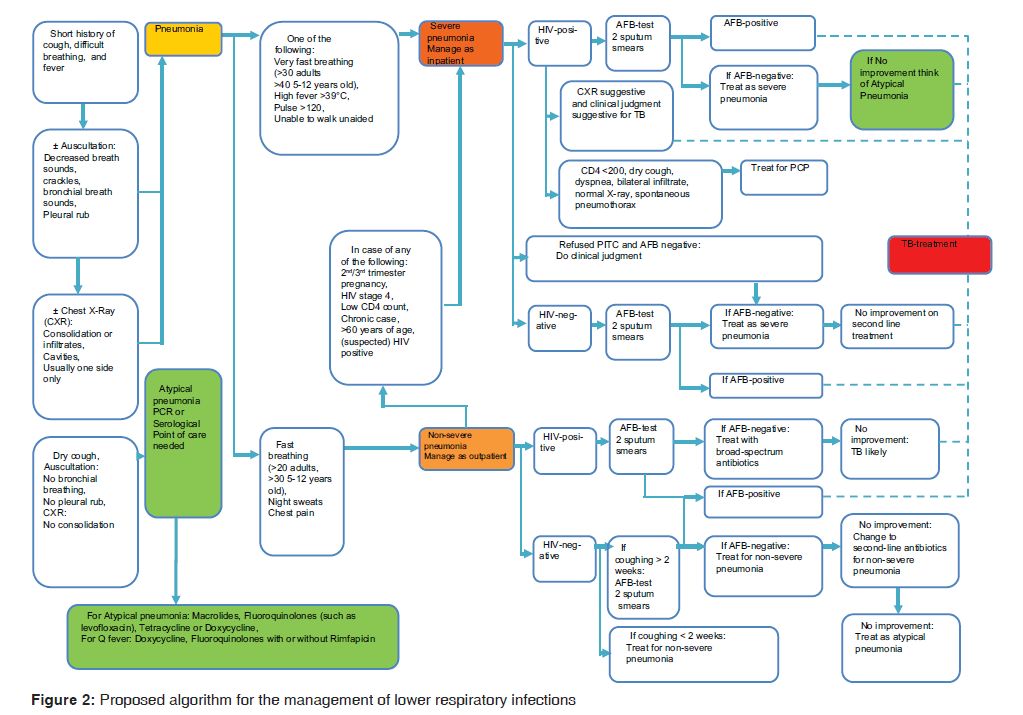

Narratives were manually compared with the proposed algorithm and the treatment recommendation from the Standard Treatment Guideline and new evidence‑based expert opinions which were used to develop Table 1 and Figure 2 for improving the practice. All narratives were stored in Excel spread sheet 2007. Transcription into themes was done by using codes and subcoded into various categories which were then manually counted to obtain summary information.

Results

A total of 53 clinician interviews were studied from the 11 health facilities shown in Table 2. In terms of qualifications, 41.5% (22/53) were clinical officers with a diploma in clinical medicine, 35.8% (19/53) were assistant medical officers with an advanced diploma in clinical medicine, 9.4% (5/53) were internship medical officers with a bachelor in clinical medicine, 7.5% (4/53) were registered medical officers with a bachelor in clinical medicine, 1.9% (1/53) were junior specialists with less than 5 years in clinical medicine, and 3.8% (2/53) were senior specialists with more than 5 years’ experience in clinical medicine.

| Facility no. | Facility level | No. of interviews |

|---|---|---|

| F01 | District Hospital | 8 |

| F02 | Health Centre | 4 |

| F03 | Regional Hospital | 6 |

| F04 | District Hospital | 5 |

| F05 | Health Centre | 2 |

| F06 | District Hospital | 8 |

| F07 | Independent Hospital | 5 |

| F08 | Health Centre | 5 |

| F09 | Designated District Hospital | 4 |

| F10 | Health Center | 2 |

| F11 | Tertiary Referral Hospital | 5 |

| Total | 53 | |

Table 2: Overview of Clinicians interviewed per facility visited

The mean age of the interviewed clinician was 40.9 (11.7) years with a range of 23 years to 71 years. Twenty‑nine clinicians 53.7% (29/53) were male, and the rest 46.3% (25/53) were female.

When asked for their presumptive diagnosis regarding the first dummy case, 83.0% (44/54) of clinicians mentioned pneumonia, 33.9% (18/53) clinicians mentioned bronchitis, 32.1% (17/53) clinicians mentioned pulmonary TB, 11.3% (6/53) mentioned upper respiratory tract infection. Other unexpected, but not easy‑to‑reject diagnoses (based on the complaints) were precharged Human Immunodeficiency Virus, (HIV) ‑ associated Pneimocistic Carinii Pneumonia (PCP), Malaria, Worm infestation, Asthma, and Hypotension. In view of what could be the additional questions to reach the definitive diagnosis, there were 16.9% (9/53) specific questions to specific diagnoses. Queries on the parameters used for assessing severity revealed that 81.1% (43/53) clinicians had skills to classify the causes of the first dummy case. However, 18.9% (10/53) clinicians could use respiratory rate as one of the parameters, but none of them could mention PSI, CURB, or CURB 65.

When asked for their presumptive diagnosis regarding the second dummy case, 47.1% (25/53) clinicians mentioned nonsevere pneumonia, 24.5% (13/53) mentioned bronchitis, 20.7% (11/53) mentioned pulmonary TB, 13.2% (7/53) for hypotension, 7.5% (4/53) severe pneumonia, 5.6% (3/53) acute upper respiratory tract infection, 3.7% (2/53) bronchiectasis, 3.7% (2/53) corpolmonale, 3.7% (2/53) unspecified respiratory infection, 3.7% (2/53) asthma, and 1.9% (1/53) PCP. Other unexpected, but not easy‑to‑reject diagnoses (based on the complaints) were thromboembolism, septic shock, septicemia, and anemia. In view of what could be the technical additional questions to reach the definitive diagnosis for the second dummy case, 60.4% (32/53) clinicians tried to classify the causes, and 11.3% (6/53) clinicians failed to mention a clear agent.

Notably, there were 15 specific questions presented by clinicians to attain particular diagnoses for LRTI 28.3% (15/53). The questions were on nature of coughing, the presence of fever, history of being admitted for healthcare delivery, duration of admission, presence of heart diseases, and smoking habits. These questions could be useful in constructing the provisional algorithm for the management of LRTI in Tanzania. For example, clinician C36 queried in the first dummy case, “Is it dry cough or productive? If productive, what is the colour of the sputum? Chest tightness or chest pain? Is he presenting with pleuritic pain? Is he smoking?” C1 mentioned “Type of sputum, blood stained, morning hours or evening? Rule out bronchiectasis by color of the sputum. History of sweating, loss of weight? Serostatus of HIV? Known asthmatic, rule out cardiac palpitation, edema lower extremities.” Regarding the second dummy case, C29 from F6 said he would ask “What is the colour of the sputum. Is cough associated with chest pain? Persistent cough? Were there any attempts for treatments before?”

In view of the parameters used for assessing severity of CAP in the second dummy case, 41.5% (22/53) clinicians mentioned respiratory rate (Breathing rate), 22.6% (12/53) did not bother what to consider, and 19/53 clinicians gave explanations that were nonspecific. Again, none of them could mention PSI, CURB, or CURB 65 as a parameter for severity of CAP.

When interviewers probed for the causative agents in atypical pneumonia, 11.3% (6/53) clinicians could mention the correct microbial agents. Chlamydia species were mentioned 5 times, Legionella species 3 times, Mycoplasma species 3 times, and C. burnetii once. Among these respondents, three were medical officer registrars: The first was a resident, second a junior specialist, and the third a senior specialist. Having a concern of pastoralists in the regions, only 13.0% (7/53) clinicians mentioned to be aware of Q‑fever and could cite the cause of Q‑fever. Three of these clinicians were medical officer registrars from the designated district hospitals (Church‑supported), three were MMED students (residents) at the referral hospital, and one was a junior specialist from the same referral hospital.

When asked for opinions, 33.9% (17/53) clinicians mentioned a need to improve laboratory premises for diagnostics follow‑up. For example, C11 (58‑year‑old at F4) stated “In our set up we have to have more investigations. Hospital needs to be more capacitated for diagnosis. There is a need of capacity building, also for the health workers on requesting and interpreting the results from laboratory.”

Ten clinicians, 18.8% (10/53) talked about detailed training for managing respiratory diseases. For example, C7 (38‑year‑old at F1) stated “It is hard to diagnose LRTI’s. If we could have continuous training, we would be capable to manage their LRTI’s.”

Eight clinicians, 15.1% (8/53) commented on thorough history taking and sufficient observation as explained by C9 (48‑year‑old at F2): “I normally diagnose by use of stethoscope and history of patient and sign and symptoms. I don’t need expensive tools to reach diagnosis.”

Seven clinicians, 14.2% (7/53) commented on the use of user‑friendly guidelines. For example, C34 (46‑year‑old at F7) stated “There should be good assessment to guide us to think diseases more than simple pneumonia to avoid using drugs without knowing what you are treating.”

Two clinicians, 3.7% (2/53) mentioned the need of improving infrastructure. C28 at (43‑year‑old at F6) stated “Improve the accommodation in the centre. Once the patient got sick they should seek medical attention immediately to a friendly facility.” Two clinicians (3.7%) were concerned about health education to the patients, as C25 at F5 stated “The health education for these LRTI groups of diseases should be routinely given.” Six clinicians had no opinions on the critical area of improvement.

Thirty‑six clinicians 67.9% (36/53) were aware of their responsibility to use Standard Treatment Guideline but only 6 (11.3%) could mention the content seen in summary recommendations derived from the Standard Treatment Guideline. Fourteen (25.9%) reported previous training in the management of patients with LRTI focusing to rule out pulmonary TB. C27 from F6 said “We should be provided with an active diagnostic guideline for all LRTIs and short seminars on all respiratory infections to update our knowledge.”

Clinicians displayed a high tendency of empirically managing patients with LRTI, as shown in Figure 3. This was well commented by C33 from F7 who said “There should be good assessment to think of something more than pneumonia to avoid using drugs without knowing what you are treating.”

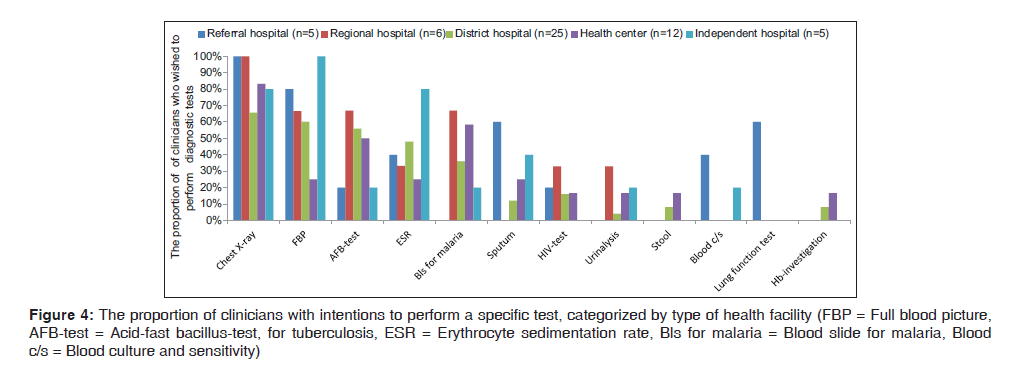

With a view to performing laboratory tests, clinicians from a health center showed a low concern for performing laboratory tests than those from district hospitals. The tests that were most often mentioned were full blood picture, sputum for acid‑fast bacillus‑test for tuberculosis (AFB), erythrocyte sedimentation rate and blood slide for malaria (Bls for malaria). For example, C38 from F6 said “No tests that I will need apart from these, unless coughing was for more than 10 days which is the case that I would do sputum for AFB”. C40 from F8 said “We diagnose most of LRTI by using only stethoscope and physical findings only”.

Blood culture and sensitivity (blood C/S) was rarely mentioned. Other diagnostic procedures rarely mentioned were pulse oxymetry, serology, bronchoalveolar lavage, bronchoscopy, CT‑scan, ECG, random blood glucose, Widal test and culture and sensitivity [Figure 4]. C27 from F6 said “Mainly we don’t have a policy. A lot are missed due to poor laboratory and essential tests for lung functioning”. Eight out of eleven facilities reported lack of technical skills for Gram‑stain sputum culture, blood C/S. For example, C29 F6 said “In big hospital like KCMC there is sputum culture, but not in our facility. I have not seen even discs for culture here.”

Figure 4: The proportion of clinicians with intentions to perform a specific test, categorized by type of health facility (FBP = Full blood picture, AFB-test = Acid-fast bacillus-test, for tuberculosis, ESR = Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, Bls for malaria = Blood slide for malaria, Blood c/s = Blood culture and sensitivity)

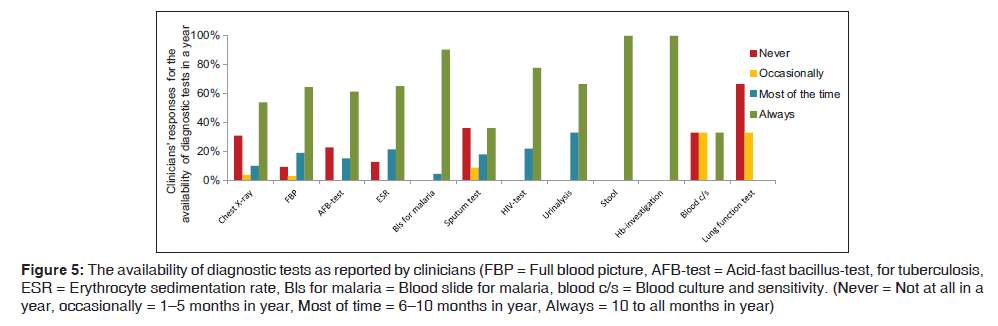

The availability of the diagnostic tests as reported to be the sole reason for unguided practice for the management of LRTI by the clinicians is shown in Figure 5. Chest X‑ray was not available in health centers and two district hospitals. At the referral hospital and the Independent Hospital, chest X‑ray was available more than 9 months per year. C45 at F9 said “For chest X‑ray we fail to get one because of poor electricity supply”. In case the patients need a chest X‑ray the patients would be referred to a regional hospital, national TB hospital, or a tertiary referral hospital.

Figure 5: The availability of diagnostic tests as reported by clinicians (FBP = Full blood picture, AFB-test = Acid-fast bacillus-test, for tuberculosis, ESR = Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, Bls for malaria = Blood slide for malaria, blood c/s = Blood culture and sensitivity. (Never = Not at all in a year, occasionally = 1–5 months in year, Most of time = 6–10 months in year, Always = 10 to all months in year)

Besides the lack of a radiology department in 81.8% (9/11) facilities, C48 from F10 commented “We don’t have X‑ray machines here, as you know it’s just a health centre that observes patients for a few days. No matter how many patients will come here.”

Ideal optimum care was derived from Figure 2 as the proposed algorithm for main reference in the situational analysis.

Discussion

Clinicians in the Kilimanjaro region demonstrate a wide variation of management skills for both severe and nonsevere pneumonia. Overall, they exhibit low awareness of universal methods and criteria to reach correct diagnoses for LRTI and rule out atypical pneumonia.

Our data provide a clue that clinicians of Tanzania tends to miss the diagnoses of LRTI. There is a strong focus to diagnose TB, following a massive campaign of TB diagnostic work out and the treatment priorities supported by HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in the absence of microbiologic methods.[39] Our study strengthens the use of clinical signs, symptoms, and thorough history taking after refining for diagnosing differential patterns of LRTI and atypical pneumonia, as recently described in Pakistan.[40]

We have shown that there is a huge gap between what clinicians are doing versus what they are required to do in reaching diagnosis and differential diagnoses. This has been described by recent studies on epidemiology, etiology, clinical features of pneumonia in developing countries.[15] There is evidence that diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs in each settings for each etiology of atypical pneumonia can be determined and defined.[2]

We have shown that clinicians exhibit widely varying methods for assessing severity of LRTIs. None of the clinicians were aware of the use of PSI, CURB‑65 as primary recommended parameters for severity assessment in the management of CAP.[41] One can support these clinicians based on the new comments on using clinicians experience and complex judgment of patients’ clinical feature.[42] However, the use of CURB‑65 and PSI is internationally recommended for the management of CAP. Therefore these parameters shall be introduced by training at a level of diploma advanced diploma and/or Degree of Medicine in Tanzania.

Despite the fact that the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare has published the latest version of Standard Treatment Guideline[35] that also guide the management of LRTI, the availability and usability of this guideline is questionable, as suggested by our study. This scenario has also been reported in South Africa for the management of CAP.[43] In developed countries, lack of awareness, concerns about practicality of using the recommended regimens, increased cost, lack of documented improved outcomes, and potential conflict with other guidelines are reported to be a cause.[44] While our study does not have confidence intervals, the qualitative evidence presented by clinicians suggested that the use of the algorithm will be helpful in the management of LRTI [Figure 2].

Majority of clinicians in Tanzania are not well guided in reaching atypical pneumonia diagnoses.[45] For example, there have been missing reports for Q‑fever for the last 15–50 years.[46] A recent report for Q‑fever from Northern Tanzania[24] has shown that atypical pneumonia caused by Coxiella spp. is not well covered by regimes in the available Tanzanian guideline. Q‑fever and many other neglected atypical pneumonia shall now be addressed by the evidence‑based guidelines in developing counties.[47]

Our study was of limited funding and by the duration of data collection such that we could not use quantitative methods for data collection throughout the region.

There is a need to translate clinical patterns into meaningful algorithms using the statistical inferences from a study with sufficient number of clinicians interviewed. Our qualitative findings in view of the current guideline for LRTI, call for prospective and retrospective quantitative data and expert opinions. Our provisional algorithm [Table 1 and Figure 2] for LRTI can be initially considered to be used in developing countries like Tanzania and used to focus on atypical pneumonia such as Q‑fever.

Conclusion

Clinicians in Kilimanjaro region exhibit a wide variation of management skills for both severe and nonsevere pneumonia. It is therefore necessary to develop and disseminate clear evidence‑based guidance for diagnosing patterns of lower respiratory infections.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the advice from Dr. Karen Retsky from Walgreens Pharmacy, Colorado, USA through Vijiji International. Prof. Bernard Hammel of Radboud University–UMCN for his mentorships. Prof. Andre Van der Ven of Nijmegen Institute of International Health of Radboud University–UMCN for his promotion and staffs of Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute, KCRI for support during data collection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Centre for International Health of Radboud University–UMCN.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369:448‑57.

- Wang K, Gill P, Perera R, Thomson A, Mant D, Harnden A. Clinical symptoms and signs for the diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children and adolescents with community‑acquired pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD009175.

- Deutscher M, Beneden CV, Burton D, Shultz A, Morgan OW, Chamany S, et al. Putting surveillance data into context: The role of health care utilization surveys in understanding population burden of pneumonia in developing countries. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2012;2:73‑81.

- Isturiz RE, Luna CM, Ramirez J. Clinical and economic burden of pneumonia among adults in Latin America. Int J Infect Dis 2010;14:e852‑6.

- Zubairi AB, Zafar A, Salahuddin N, Haque AS, Waheed S, Khan JA. Atypical pathogens causing community‑acquired pneumonia in adults. J Pak Med Assoc 2012;62:653‑6.

- Nicolini A, Ferraioli G, Senarega R. Severe Legionella pneumophila pneumonia and non‑invasive ventilation: Presentation of two cases and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2013;81:399‑403.

- Riantawan P, Nunthapisud P. Psittacosis pneumonia: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Assoc Thai 1996;79:55‑9.

- Karagöz S, Kiliç S, Berk E, Uzel A, Çelebi B, Çomoglu S, et al. Francisella tularensis bacteremia: Report of two cases and review of the literature. New Microbiol 2013;36:315‑23.

- Marrie TJ. Coxiella burnetii pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2003;21:713‑9.

- Bao Z, Yuan X, Wang L, Sun Y, Dong X. The incidence and etiology of community‑acquired pneumonia in fever outpatients. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012;237:1256‑61.

- Puolakkainen M. Laboratory diagnosis of persistent human chlamydial infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2013;3:99.

- Chiappini E, Venturini E, Galli L, Novelli V, de Martino M. Diagnostic features of community‑acquired pneumonia in children: What’s new? Acta Paediatr Suppl 2013;102:17‑24.

- Ari MD, Guracha A, Fadeel MA, Njuguna C, Njenga MK, Kalani R, et al. Challenges of establishing the correct diagnosis of outbreaks of acute febrile illnesses in Africa: The case of a likely Brucella outbreak among nomadic pastoralists, Northeast Kenya, March‑July 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011;85:909‑12.

- Petti CA, Polage CR, Quinn TC, Ronald AR, Sande MA. Laboratory medicine in Africa: A barrier to effective health care. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:377‑82.

- Lanaspa M, Annamalay AA, LeSouëf P, Bassat Q. Epidemiology, etiology, x‑ray features, importance of co‑infections and clinical features of viral pneumonia in developing countries. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014;12:31‑47.

- Halm EA, Atlas SJ, Borowsky LH, Benzer TI, Singer DE. Change in physician knowledge and attitudes after implementation of a pneumonia practice guideline. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:688‑94.

- Crump JA, Morrissey AB, Nicholson WL, Massung RF, Stoddard RA, Galloway RL, et al. Etiology of severe non‑malaria febrile illness in Northern Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e2324.

- World Health Organization. IMAI District Clinician Manual: Hospital Care for Adolescents and Adults: Guidelines for the Management of Illnesses With Limited Resources. WHO, Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Steinmann P, Bonfoh B, Péter O, Schelling E, Traoré M, Zinsstag J. Seroprevalence of Q‑fever in febrile individuals in Mali. Trop Med Int Health 2005;10:612‑7.

- Mediannikov O, Fenollar F, Socolovschi C, Diatta G, Bassene H, Molez JF, et al.Coxiella burnetii in humans and ticks in rural Senegal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4:e654.

- Gumi B, Firdessa R, Yamuah L, Sori T, Tolosa T, Aseffa A, et al. Seroprevalence of Brucellosis and Q‑Fever in Southeast Ethiopian Pastoral Livestock. J Vet Sci Med Diagn 2013;2:1 Author manuscript from Europe PMC Funders Group as an Author Manuscript available in PMC 2013 December

- Published in final edited form as: J Vet Sci Med Diagn. 2013 March 22; 2 (1): doi: 10.4172/2325‑9590.1000109.

- Knobel DL, Maina AN, Cutler SJ, Ogola E, Feikin DR, Junghae M, et al.Coxiella burnetii in humans, domestic ruminants, and ticks in rural western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;88:513‑8.

- Potasman I, Rzotkiewicz S, Pick N, Keysary A. Outbreak of Q fever following a safari trip. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:214‑5.

- Prabhu M, Nicholson WL, Roche AJ, Kersh GJ, Fitzpatrick KA, Oliver LD, et al. Q fever, spotted fever group, and typhus group rickettsioses among hospitalized febrile patients in Northern Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:e8‑15.

- van Wijk MJ, Maas DW, Renders NH, Hermans MH, Zaaijer HL, Hogema BM. Screening of post‑mortem tissue donors for Coxiella burnetii infection after large outbreaks of Q fever in The Netherlands. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:6.

- Bjork A, Marsden‑Haug N, Nett RJ, Kersh GJ, Nicholson W, Gibson D, et al. First reported multistate human Q fever outbreak in the United States, 2011. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2014;14:111‑7.

- Anderson A, Bijlmer H, Fournier PE, Graves S, Hartzell J, Kersh GJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of Q fever -United States, 2013: Recommendations from CDC and the Q Fever Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013;62:1‑30.

- Moodie CE, Thompson HA, Meltzer MI, Swerdlow DL. Prophylaxis after exposure to Coxiella burnetii. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1558‑66.

- van der Hoek W, Sarge‑Njie R, Herremans T, Chisnall T, Okebe J, Oriero E, et al. Short communication: Prevalence of antibodies against Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) in children in The Gambia, West Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:850‑3.

- Crump JA, Gove S, Parry CM. Management of adolescents and adults with febrile illness in resource limited areas. BMJ 2011;343:d4847.

- Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Hanusa BH, Weissfeld LA, Singer DE, et al. A prediction rule to identify low‑risk patients with community‑acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243‑50.

- Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, Boersma WG, Karalus N, Town GI, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: An international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58:377‑82.

- Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, Fine MJ, Fuller AJ, Stirling R, et al. SMART‑COP: A tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community‑acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:375‑84.

- España PP, Capelastegui A, Gorordo I, Esteban C, Oribe M, Ortega M, et al. Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe community‑acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:1249‑56.

- Tanzanian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW). Standard Treatment Guidelines (STG) and Essential Medicines List (NEMLIT) -Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: World Health Organization (WHO); 2013.

- National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme (NTLP) National Aids Control Programme, NACP and, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW). Manual for Health Care Workers at TB clinics and HIV Care and Treatment Centers Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Tanzania: MOHSW; 2008.

- The working group of South African Thoracic Society. Management of community‑acquired pneumonia in adults. S Afr Med J 2007;97:1295‑306.

- Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Singh N, Mishra N, Khilnani GC, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of community‑ and hospital‑acquired pneumonia in adults: Joint ICS/NCCP (I) recommendations. Lung India 2012;29 Suppl 2:S27‑62.

- Assefa G, Nigussie Y, Aderaye G, Worku A, Lindquist L. Chest X‑ray evaluation of pneumonia‑like syndromes in smear negative HIV‑positive patients with atypical chest x‑ray. Findings in Ethiopian setting. Ethiop Med J 2011;49:35‑42.

- Mahmood K, Akhtar T, Naeem M, Talib A, Haider I, Siraj‑Us‑Salikeen. Fever of unknown origin at a teritiary care teaching hospital in Pakistan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2013;44:503‑11.

- Kwok CS, Loke YK, Woo K, Myint PK. Risk prediction models for mortality in community‑acquired pneumonia: A systematic review. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:504136.

- Froes F. PSI, CURB‑65, SMART‑COP or SCAP? And the winner is. SMART DOCTORS. Rev Port Pneumol 2013;19:243‑4.

- Nyamande K, Lalloo UG. Poor adherence to South African guidelines for the management of community‑acquired pneumonia. S Afr Med J 2007;97:601‑3.

- El‑Solh AA, Alhajhusain A, Saliba RG, Drinka P. Physicians’attitudes toward guidelines for the treatment of hospitalized nursing home‑acquired pneumonia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:270‑6.

- Nyamande K, Lalloo UG, Vawda F. Comparison of plain chest radiography and high‑resolution CT in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients with community‑acquired pneumonia: A sub‑Saharan Africa study. Br J Radiol 2007;80:302‑6.

- Anstey NM, Tissot Dupont H, Hahn CG, Mwaikambo ED, McDonald MI, Raoult D, et al. Seroepidemiology of Rickettsia typhi, spotted fever group rickettsiae, and Coxiella burnetti infection in pregnant women from urban Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1997;57:187‑9.

- Hertz JT, Munishi OM, Ooi EE, Howe S, Lim WY, Chow A, et al. Chikungunya and dengue fever among hospitalized febrile patients in Northern Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;86:171‑7.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.