Topographical Characterization of Children with Cerebral Palsy

2 Department of physiotherapy, Riphah international university, Pakistan

3 Department of physiotherapy, Royal Institute of Health Science, Pakistan

Published: 03-May-2022, DOI: 10.54608.annalsmedical.2022.41

Citation: Hassan Z, et al. Topographical Characterization of Children with Cerebral Palsy. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2022;12

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Objective: The fundamental aim of the examination was to discover the commonness of cerebral palsy by its portrayal like topographical conveyance and its relationship with GMFCS and MACS levels.

Methods: Data was collected by using a self-made questionnaire to gather data on sociodemographic data according to topographical distribution. Information was gathered from CP children of various enrolled institutes of Lahore (Hamza Foundation, Pakistan Society for the Rehabilitation and Disabled (PSRD), Rising Sun institute, Children Hospital Lahore, Combined Military Hospital Lahore (CMH)). Sample size was computed utilizing the online epitools software. MACS and GMFCS scales were applied. Descriptive studies were used to analyse the data.

Results: Results showed that quadriplegia is the most frequently occurring followed by diplegia and hemiplegia. Classification of GMFCS levels and MACS levels through topographic distribution was also find out. Results showed the highest percentage of quadriplegic patients at level 3 of both GMFCS and MACS scales, whereas the least count noted was no hemiplegic child at level 1 or quadriplegic at level 4 of MACS scale.

Conclusion: CP is chronic disorder distinguished worldwide. The study portray gross motor and fine motor capacities, clinical subtypes and other related physical complications in children with CP. The result of this analysis aids in explaining the prevalence of CP by its characterization like topographic distribution, general health and associated conditions in children.

Keywords

GMFCS; MACS; Diplegia; Quadriplegia

Introduction

Cerebral palsy is a physical incapacity that influences posture and movement. It is an umbrella term having clutters of disorders, which totally affects a person’s ability to move. Injury to the developing brain suddenly after birth or amid pregnancy is the major cause of disorder. Motor disabilities are classified into primary and secondary motor deficiencies. Primary deficiencies are postural steadiness, spasticity, involvement distribution, quality of movement and secondary disabilities include movement restrictions, ROM, strength and endurance [1]. Besides, sensory deficits, chronic musculoskeletal discomfort, cognitive limitations and joint deformities are also experienced by particulars with CP [2,3]. Cerebral Palsy influences individuals in different ways and influences balance, muscle coordination, body development, stance, reflex, muscle tone and muscle control [4].

Classification of CP depending on motor disability of the organs or appendages, and on the basis of restrictions to the ADLs performed by an individual [5]. Manual amplitude and mobility in individuals with cerebral palsy are depicted by Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) and The Gross Motor Function Classification System-Expanded (GMFCS) respectively. Now lately Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System and the Communication Function Classification System has been introduced to portray these capacities [6].

CP is additionally grouped by the topographic dispersion of muscle spasticity [7]. This strategy characterizes kids as diplegic, (reciprocal association with leg contribution more noteworthy than arm inclusion), hemiplegic (one-sided contribution), or quadriplegic (respective association with arm contribution equivalent to or more prominent than leg association) [8].

According to Jason Howard et all, GMFCS scale varied from 35% at level 1 to 18% at level [5]. Topographical distribution also showed a fairly equal distribution with the highest percentage of quadriplegic children (37%), followed by hemiplegia (35%) and diplegia (28%) [9].

Jam William goter in 2004 conducted a longitudinal cohort study in Canada to classify the topographical distribution and the relationship between GMFCS and type of motor impairment. 657 children between the ages of 1-13years were selected for the study. Results showed the most hemiplegics at level 1 of GMFCS scale. Classification by limb distribution and GMFCS levels were statistically analysed which showed a significant chi square value i.e. less than 0.0059.

The Rationale of the study was to give a confirmation based portrayal of children with cerebral paralysis. Current investigation had tended to the portrayal of children with cerebral paralysis which was inadequate in existing writing. With the goal that Community can be profited by knowing the commonness of Cerebral Palsy by its portrayal in kids.

Patients and Methods

It was a cross-sectional study to rule out the prevalence of topographical characterization of children with cerebral palsy. Duration of study was six months. Data was collected from CP children of different registered hospitals of Lahore (Pakistan Society for the Rehabilitation and Disabled (PSRD), Combined Military Hospital Lahore (CMH), Children Hospital Lahore, Rising Sun institute, Hamza Foundation). Sample size was calculated using the online epitools software for sample size calculation proportions. An assumed prevalence of 3.3% of children with CP in US was used from a previous research and precision of 0.04 [10]. To allow for adequate sub analysis, confidence interval of 0.99 was selected to give a sample size of 98. Although 108 children were selected as final target sample size for more accurate results and allowance for nonresponsiveness. Out of which guardians of 104 responded and 4 did not respond. Data was then entered to SPSS version 20.1. The quantitative variables were elaborated by means and standard deviation while variables of qualitative nature by formulating frequency charts, tables and bar graphs.

Results

Results in Table 1 showed that quadriplegia (47.1%) is the most frequently occurring followed by diplegia (27.9%) and hemiplegia (25.0%).

| Table 1: Frequency of topographic distribution. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | ||

| Hemiplegia | 26 | 25 | |

| Diplegia | 29 | 27.9 | |

| Quadriplegia | 49 | 47.1 | |

| Total | 104 | 100 | |

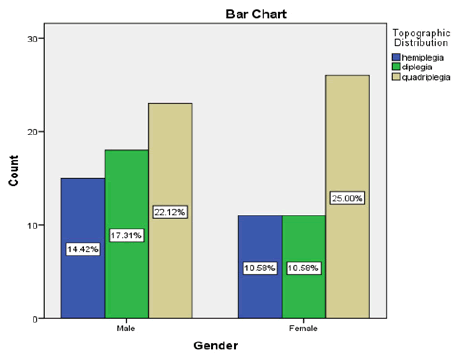

Figure 1 showed classification of topographic distribution through gender. The graph showed that among males, the most percentage is of quadriplegic (22.12%) patients followed by diplegics (17.31%) and then quadriplegics (14.42%). In case of females, quadriplegia been the highest percentage i.e. 25% while the hemiplegics and quadriplegics had the same percentage i.e. 10.58%.

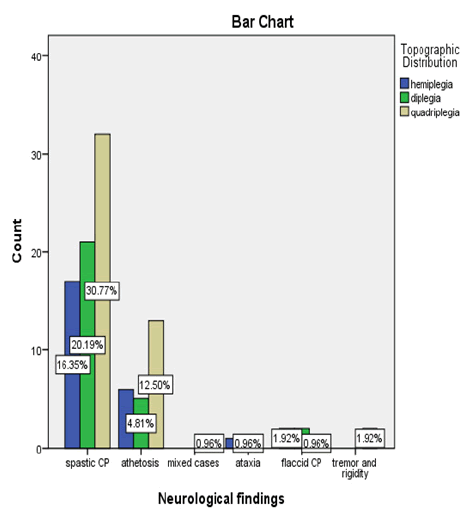

The graph in Figure 2 showed classification of GMFCS levels through topographic distribution. It showed the highest percentage of quadriplegic patients at level 3 followed by diplegics at level 2 and hemiplegics at level 1. Least percentage of children were reported of having level 4. Significant association was seen between the two variables as p-value was less than 0.05.

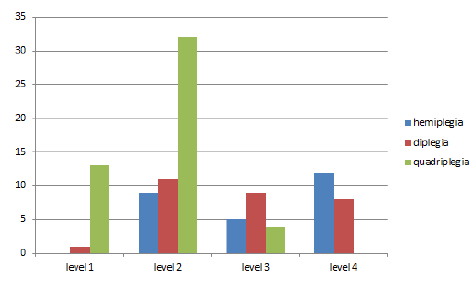

Figure 3 showed classification of MACS levels through topographic distribution. The graph showed a high percentage of quadriplegic children at level 3 of MACS scale, whereas the least count noted was no hemiplegic child at level 1 or quadriplegic at level 4. Significant association is seen between the two variables as p-value is less than 0.05.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to find out the characterization of children with CP according to topographic distribution, MACS and GMFCS.

The sample consisted of 104 participants of cerebral palsy. Caregivers, guardians and parents of all participants were requested to answer the questions.

For representing the results statistically Chi Square Test was used. The outcomes demonstrated that significant association was seen between topographic distributions, GMFCS MACS.

Results showed the topographic distribution explaining that quadriplegia (47.1%) is the most frequently occurring followed by diplegia (27.9%) and hemiplegia (25.0%). A consensus in the literature also showed that quadriplegia is the most occurring type of cerebral palsy in children [9].

According to Figure 4, among 104 participants, 53.8% were male while only 46.15% were females. . Although there is a consensus in the literature which tell us that CP is most common in males as compared to females and spastic type is the most prevalent CP type, whereas the topographic distribution is variable among variables [11].

The GMFCS and MACS levels through topographic distribution were also find out. It showed that of the participants with spastic CP, 24.3% were hemiplegic, 30% were suffering from diplegia while 45.7% were classified as quadriplegia.

Jam William goter in 2004 conducted a longitudinal cohort study in Canada to classify the topographical distribution and the relationship between GMFCS and type of motor impairment. 657 children between the ages of 1 years-13 years were selected for the study. Results showed the most hemiplegics at level 1 of GMFCS scale. Classification by limb distribution and GMFCS levels were statistically analysed which showed a significant chi square value i.e less than 0.0059.

As for GMFCS, most of the participants were classified at level III’ followed by level II, I and least i.e. no child was at level IV. The results showed that quadriplegics showed the highest percentage with level III, 14.42% diplegics were at level II and 11.54% hemiplegics were reported with level I. The consensus of the literature showed that the investigation assessed isometric lower appendage muscle quality in 50 ambulant youngster with spastic diplegia at GMFCS levels I, level II and level III, with n=14 at level I, n=26 at level II and n=10 at level III. K himmelman said that GMFCS distributed at Level I in 32%, Level II in 29%, Level III in 8%, Level IV in 15%, and Level V in 16% [12].

The results showed a high percentage of quadriplegic children at level III of MACS scale, whereas the least count noted was no hemiplegic child at level 1 or quadriplegic at level [4]. A significant chi square value of 0.00 is observed which means there is a significant relationship between the two categorical variables.

Conclusion

CP is a chronic disorder distinguished worldwide in the world. This study portray topographically clinical subtype and other related physical complications in children with CP. The result of this analysis aids in explaining the prevalence of CP by its characterization like topographical findings.

References

- Odding E, Roebroeck ME, Stam HJ. The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: incidence, impairments and risk factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:183-91.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Abanto J, Ortega AO, Raggio DP, Bönecker M, Mendes FM, Ciamponi AL. Impact of oral diseases and disorders on oral‐health‐related quality of life of children with cerebral palsy. Spec Care Dentist. 2014;34:56-63.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Bartlett DJ, Chiarello LA, Mccoy SW, Palisano RJ, Jeffries L, Fiss AL, et al. Determinants of gross motor function of young children with cerebral palsy: A prospective cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:275-82.

- Blair E. Epidemiology of the cerebral palsies. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41:441-55.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Rethlefsen SA, Ryan DD, Kay RM. Classification systems in cerebral palsy. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41:457-67.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Gorter JW, Rosenbaum PL, Hanna SE, Palisano RJ, Bartlett DJ, Russell DJ, et al. Limb distribution, motor impairment, and functional classification of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:461-7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Becher J. Pediatric rehabilitation in children with cerebral palsy: General management, classification of motor disorders. JPO: Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics. 2002;14:143-9.

- O’Shea TM. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cerebral palsy in near-term/term infants. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:816.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Howard J, Soo B, Graham HK, Boyd RN, Reid S, Lanigan A, et al. Cerebral palsy in Victoria: Motor types, topography and gross motor function. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:479-83.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Kirby RS, Wingate MS, Braun KVN, Doernberg NS, Arneson CL, Benedict RE, et al. Prevalence and functioning of children with cerebral palsy in four areas of the United States in 2006: A report from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:462-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Margre AL, Reis MG, Morais RL. Caracterization of adults with cerebral palsy. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2010;14:417-25.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Himmelmann K, Beckung E, Hagberg G, Uvebrant P. Gross and fine motor function and accompanying impairments in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:417-23.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a bi-monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a bi-monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.