Health Insurance and User Fees: A Survey of Health Service Utilization and Payment Method in Mushin LGA, Lagos, Nigeria

2 Lagos State Ministry of Health, Nigeria, Email: christy588@gmail.com

3 AIICO-Multishield Ltd, Nigeria, Email: leke5842@gmail.com

4 Royal Cross Medical Centre, Lagos, Nigeria, Email: oluseyi5485@gmail.com

Citation: Roberts AA, et al. Health insurance and user fees: A survey of health service utilization and payment method in Mushin LGA, Lagos, Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2018; 8: 93-99

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Studies have documented how out-of-pocket payments (OOP) and user fees result in catastrophic health expenditures, providing evidence that health systems are better financed through prepayment mechanisms such as health insurance. Aim: This study sought to determine the perception of community residents to health insurance, their pattern of health service utilization and method and amount of payment. Methods: This descriptive cross-sectional study among 422 household members in Mushin LGA obtained data on sociodemographic characteristics, perception of health insurance, enrollment status and willingness to enroll; last use of health services and method of payment for health care services. Data analysis was done with Epi-info (ver 7) and results were presented as frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. Statistically significant associations were determined using the Chi-square test at significance level of p < 0.05. Results: Over half the respondents (56.6%) had not heard about health insurance. Very few (19.7%) were enrolled. Of those not enrolled, 57.1% were willing to consider buying health insurance. The method of payment for health services reported by respondents was OOP (98.3%). Those in younger age groups, with higher levels of education and higher household incomes reported having heard of health insurance. Higher educational level and household incomes were positively associated with willingness to enroll in a health insurance scheme. Conclusion: Awareness was insufficient, health services were paid for mostly from OOP. The authors recommend taking the opportunity to encourage uptake of health insurance for young adults and those in low- and middle-income households.

Keywords

Health Insurance; User Fees; Out-of-Pocket Expenditure; Lagos; Nigeria

Introduction

Health systems should provide preventive and curative health services that can ensure the health and wellbeing of community residents. However, it is documented that there are financial barriers to accessing these services can result in people having to use considerable proportions of their household income thereby pushing many households into poverty. [1,2] Making the users of health services pay out of pocket for the services they receive has the potential effect of impoverishing some households that choose to seek services while excluding others from seeking health care. In Nigeria, private health expenditure as a percentage of total health expenditure was 68.5% in 2010. This is made up of out-of-pocket (OOP) personal resources, and constituted 95.6% of private expenditure on health. [3]

There is vested collective interest in a national commitment to universal health coverage. Apart from the fact that it is a fundamental human right, there are negative effects of poor health outcomes from the individual to the community, between resource-poor and resource-rich communities and even from poor to rich countries. [4]

The health system in Nigeria has, post colonially, developed along different lines which led to fragmentation of the health system along formal and informal, public and private service provision. [5] Following the World Health Assembly of 2005 which called for all health systems to move towards universal coverage, Nigeria initiated, developed and implemented a social health insurance policy called the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). [6,7] Studies have been conducted to examine how out-of-pocket payments and user fees result in catastrophic health expenditures, how financial protection to the informal sector can be provided; and ways that public resources can be more equitably allocated, providing evidence that health systems are better financed through prepayment mechanisms such as health insurance and general taxation than through user-fees. [8]

With the costs of both infectious and non-communicable disease amounting to 7.03% of monthly household incomes in parts of the country, it is essential that improving universal health coverage early in the disease processes is addressed. [9]

However, there are still gaps in the awareness and utilization of pre-payment and social insurance schemes even among formal sector workers, as well as informal workers and community residents. [10] This study sought to determine the perception of community residents to health insurance, their pattern of health service utilization and method and amount of payment.

Methods

Study background and participant selection

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out among 422 household members between the months of June and September 2014 in Mushin local government area (LGA) in Lagos state. Mushin is one of twenty local government areas (LGA) of Lagos state with a cross section of different socioeconomic groups and socio-economic strata. Majority of the residents are engaged in trading of commodities as diverse as petty trading of perishables to motor spare parts. It is home to local and federal civil servants, and people employed in the formal and informal private sector. There are several markets in the LGA, three comprehensive primary health care centres, and many private and public primary and secondary schools. The Lagos University Teaching Hospital is located on the border of Mushin and Surulere LGAs.

The study participants were household members aged over 18 years, related to, if not, the household head and resident in the area for 2 or more years. The sample size of 422 was determined from the formula for descriptive cross-sectional studies [11] Z2pq /d2 , at 95% confidence limits, using a prevalence of catastrophic health expenditure in public health institutions with user fees of 0.48 obtained from a previous study, [12] and with a markup of 10%. Multistage sampling was used to select study participants from 7 of nineteen wards, 6 streets per ward and targeting 10 houses per street. Where there were more than one household in the house, 1 household member was selected by balloting from among those immediately available. In the event that the household head may have gone to work, the only eligibility criterion employed for choosing the study participant was any household member present aged 18 years or older, whose biological relationship to the head could be established.

Study variables and definitions

Data was collected using a structured household-level questionnaire with close-ended questions developed from review of literature. [5,13-17] The main outcome variables were the perception of community residents to health insurance, their pattern of use of health facilities and method of payment for services. Perception was measured by asking whether respondents knew of the existence of health insurance schemes and whether they were enrolled in a scheme. Patterns of use of health facilities documented the last time they used a health facility, and the health complaints necessitating the visit, whether or not they engaged in self-medication and their reasons for doing so – if they did. The method and amount of payment for their last visit to a health facility included asking whether those not enrolled in a scheme were willing to consider buying health insurance.

Data collection and management

Information about the independent variables were collected on the socio-demographic characteristics, self-reported illness profile, healthcare seeking behaviour, and healthcare expenditure. Data was obtained on the socio-demographic characteristics of age of respondent (as at last birthday), sex, educational status, marital status and estimated household monthly income. Perception of health insurance was determined by asking whether they knew about it, whether they were enrolled, how it was paid for (if enrolled) and/or their willingness to enroll. Method of payment for health care services was asked using either of two major methods: paying out of pocket (OOP) or using health insurance. OOP payment was estimated as the sum of all healthcare related expenditures made within the month preceding the survey. The questionnaire was field tested and refined. Trained data collectors, with similar socioeconomic background to that of the respondents and fluent in the local languages, administered the questionnaire.

Data analysis was done with Epi-info (ver 3.5.4) and results were presented as frequencies and percentages, means and standard deviations. Statistically significant associations were determined using the Chi-square test at significance level of p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from human research and ethics committee of Lagos University Teaching Hospital. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the executive chairman of Mushin LGA. Written informed consent was sought from each participant once it clear they understand the purpose of the study. The respondents were assured of total confidentiality and their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. [18]

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Respondents had a mean age of 34.7+ 6.9 years. They were more males, 62.8% (265/422) married, 67.5% (285/422), of Christian faith, 62.3% (265/422), with mostly secondary, 55.2% (233/422) and post-secondary education, 36% (152/422) [Table 1]. Respondents were household heads, 54.7% (231/422), spouses, 27.0% (114/422) or children, 11.1% (47/422) of household heads. Almost a third, 29.6% (125/422) reported a monthly household income of less than N10,000 (equivalent to <$2 a day); however, 96.4% (407/422) owned mobile phones, 90.8% (383/422) owned television sets and 52.1% (220/422) owned generators (size not indicated) [Table 1].

| Demographic Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age of the respondents | |

| <20 | 6 (1.4) |

| 21-30 | 71 (16.8) |

| 31-40 | 161 (38.2) |

| 41-50 | 83 (19.7) |

| 51-60 | 60 (14.2) |

| 61and over | 41 (9.7) |

| Sex of the respondents | |

| Male | 265 (62.8) |

| Female | 157 (37.2) |

| Position in household | |

| Head of household | 231 (54.7) |

| Spouse | 114 (27.0) |

| Children | 47 (11.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 81 (19.2) |

| Married | 285 (67.5) |

| Separated | 26 (6.2) |

| Divorced | 11 (2.6) |

| Widowed | 19 (4.5) |

| Educational level | |

| Primary | 20 (4.7) |

| Secondary | 233 (55.2) |

| Post-secondary | 152 (36.0) |

| Quranic/vocational | 17 (4.0) |

| Monthly Household Income | |

| < N5,000 | 29 (6.9) |

| N5,100 – N10,000 | 96 (22.7) |

| N10,100 – N25,000 | 138 (32.7) |

| >N25,000 | 159 (37.7) |

Table 1: Socio-demographic distribution of respondents (N=422).

Awareness of health insurance and health service utilization patterns

The mean amount (SD) spent on hospital bills for registration, consultation, investigations admissions and drugs was N10, 357.35 (N6, 450.76); expenditure for self-medication ranged from N20 to N70,000 with a mean (SD) of N13,583.95 (N6,238.75) and costs for prescribed routine medications ranged from N200 to N100,000. The reported mean (SD) monthly expenditure for eye glasses and dental care was N14,488.97 (N6,738.30) [Table 2].

| Description of expenditure | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Hospital bills (registration, consultation,investigations, admission and drugs) | N10,357. 35 + N6,450.76 |

| Self-medication | N13,583.95 + N6,238.75 |

| Prescribed routine medications | N16,539.66 + N14,256.10 |

| Special costs for eye glasses and dental care | N14,488.97 ÂÂ+ N6,738.30 |

Table 2: Mean monthly expenditure on healthcare.

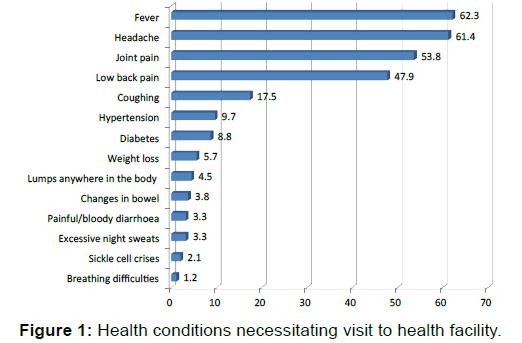

Over half of the respondents, 51.7% (218/422) could not remember when they had last used a health service facility; however, of those that had done so, 62.3% (127/204) reported doing so more than a month prior to the survey. Majority, 86.5% (365/422) reported using personal savings to pay. Other sources of money were borrowing money, 6.2% (26/422), accepting help from friends/relations, 5.7% (24/422) and health insurance, 1.7% (7/422). Almost three-quarters of respondents, 71.6% (302/422) reported treating themselves before seeking help outside the home and the major reasons were the perception that the illness was not serious, 73.0% (220/422), self-medication was the cheaper option, 71.1% (214/422) and they knew what medicine to take, 64.2% (194/422) [Table 3]. The major reasons for visiting health facilities were fever, 62.3% (263/422), headaches, 61.4% (259/422), joint pains, 53.8% (227/422) and low back pain, 47.9% (202/422) [Figure 1].

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| When last visit to health facility was made | |

| Past week | 33 (7.8) |

| Between one week to one month ago | 44 (10.4) |

| More than a month ago | 127 (30.1) |

| Don’t remember | 218 (51.7) |

| Source of funds to make payment at last visit to facility | |

| Personal savings | 365 (86.5) |

| Borrowed from friends | 26 (6.2) |

| Contributions from friends/family | 24 (5.7) |

| Health insurance | 7 (1.7) |

| Treats oneself before seeking help outside the house | |

| Yes | 302 (71.6) |

| No | 120 (28.4) |

| Reasons for self-medication before going to the hospital* (n=302) | |

| It is cheap | 214 (71.1) |

| Illness is not serious | 220 (73.0) |

| Distance to the health facility is too far | 117 (38.6) |

| Religious/traditional beliefs | 69 (22.7) |

| Chemists are nearer | 185 (61.4) |

| I know what medicine to take | 194 (64.2) |

| Health workers are unfriendly | 89 (29.6) |

| Health workers are not always available at the health facility | 65 (21.6) |

| I take native medication (agbo) | 151 (50.0) |

| *multiple responses permitted | |

Table 3: Pattern of respondents’ health facility utilization (n=422).

Over half the respondents, 56.6% (239/422) had not heard about health insurance. One hundred and eighty-three respondents (43.4%) had heard of health insurance schemes, and of that proportion, 36/183 (19.7%) were enrolled in a scheme. Of those that had registered with any type of insurance scheme payment was either by government, 47.2% (17/36), their employer, 38.9% (14/36) or themselves, 13.9% (5/36). Of those had either not heard (239/422), or heard but not enrolled (147/183), 57.1% (220/386) were willing to consider buying health insurance [Table 4].

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ever heard about health insurance (N=422) Yes | 183 (43.4) | |

| Enrolled in health insurance scheme (N=183) Yes | 36 (19.7) | |

| Method of payment as an health insurance enrollee (N=36) | ||

| Myself | 5 (13.9) | |

| Government | 17 (47.2) | |

| Company | 14 (38.9) | |

| Willing to consider buying health insurance (N=386) Yes | 220 (57.1) | |

Table 4: Distribution of respondents’ perception of health insurance.

Age of the respondents, educational level and household incomes were significantly correlated to whether the respondents had heard of health insurance. Those in younger age groups, with higher levels of education and higher household incomes were associated with having heard of health insurance. However, only higher educational level and household incomes were positively associated with willingness to enroll in a health insurance scheme [Table 5].

| Have you heard of health insurance | N=422 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Yes | No | |

| Male | 112 (42.3) | 153 (57.7) | χ2 = 0.2 |

| Female | 71 (45.2) | 86 (54.8) | P = 0.62 |

| Age | |||

| <20 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | |

| 21-30 | 33 (46.5) | 38 (53.5) | χ2= 20.8 |

| 31-40 | 89 (55.3) | 72 (44.7) | P = 0.004 |

| 41-50 | 29 (34.9) | 54 (65.1) | |

| 51-60 | 19 (31.7) | 41 (68.3) | |

| 61and over | 12 (30.0) | 28 (70.0) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | |

| Secondary | 71 (30.5) | 162 (69.5) | χ2 = 68.1 |

| Post-secondary | 105 (69.1) | 47 (30.9) | P <0.0000 |

| Quranic/Vocational | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Household monthly income | |||

| <N5,000 | 9 (32.1) | 19 (67.9) | |

| N5,100-N10,000 | 36 (37.9) | 59 (62.1) | χ2 = 23.8 |

| N10,000-N25,000 | 44 (32.1) | 93 (67.9) | P <0.0001 |

| >N25,000 | 94 (58.0) | 68 (42.0) | |

| Willingness to enroll in health insurance | N=239 | ||

| Sex | Yes | No | |

| Male | 62 (59.6) | 42 (40.4) | χ2 = 0.04 |

| Female | 41 (56.9) | 31 (43.1) | P = 0.84 |

| Age | |||

| <20 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 21-30 | 16 (53.3) | 14 (46.7) | χ2= 1.78 |

| 31-40 | 39 (60.9) | 25 (39.1) | P = 0.78 |

| 41-50 | 16 (59.3) | 11 (40.7) | |

| 51-60 | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | |

| 61and over | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 1 (33.3 | 2 (66.7) | |

| Secondary | 18 (27.7) | 47 (72.3) | χ2 = 53.09 |

| Post-secondary | 84 (80.8) | 20 (19.2) | P <0.0001 |

| Quranic/Vocational | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Household monthly income | |||

| <N5,000 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | |

| N5,100-N10,000 | 6 (16.7) | 30 (83.3) | χ2 = 42.23 |

| N10,000-N25,000 | 25 (58.1) | 18 (41.9) | P <0.0001 |

| >N25,000 | 17 (77.2) | 21 (22.8) | |

Table 5:Socio-economic correlates of respondents’ awareness of and willingness to enrol in health insurance.

Except for the sex of the respondents, there was no statistically significant association between the ages, educational levels or monthly household incomes of the respondents and decision to treat oneself at home before seeking treatment outside. Women tended not to treat themselves at home prior to seeking care [Table 6].

| Home treatment before seeking healthcare | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Age | |||

| <20 | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | |

| 21-30 | 47 (66.2) | 24 (33.8) | χ2 = 8.29 |

| 31-40 | 110 (68.3) | 51 (31.7) | P = 0.08 |

| 41-50 | 61 (73.5) | 22 (26.5) | |

| 51-60 | 50 (83.3) | 10 (16.7) | |

| 61and over | 32 (78.0) | 9 (22.0) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 204 (77.0) | 61 (23.0) | χ2 = 10.2 |

| Female | 98 (62.4) | 59 (37.6) | P = 0.001 |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 15 (75.0) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Secondary | 162 (69.5) | 71 (30.5) | χ2 = 1.9 |

| Post-secondary | 114 (75.0) | 38 (25.0) | P = 0.6 |

| Quranic/Vocational | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Household monthly income | |||

| <N5,000 | 17 (58.6) | 12 (41.4) | |

| N5,100-N10,000 | 60 (62.5) | 36 (37.5) | χ2 = 7.03 |

| N10,000-N25,000 | 105 (76.1) | 33 (23.9) | P = 0.07 |

| >N25,000 | 114 (71.7) | 45 (28.3) | |

Table 6:Socio-economic correlates of home treatment.

Discussion

Low level of awareness of health insurance still exists in this community despite the efforts of government to ensure wider coverage. [19] This study did not establish the time sequence between knowledge of, and enrollment into a health insurance scheme. It is quite possible that, given the fact that 69.5% of those enrolled had their premiums paid by either government or the company; enrollment in the scheme probably informed the knowledge that respondents had.

Findings from this study confirmed that those with lower monthly household incomes have a pattern of engaging more in pre-facility home treatment before seeking healthcare. Financial access to health services has been reported as contributing to the pattern of utilization with documented evidence of reduced access by people with lower household incomes and those who face high care-seeking costs. [20,21] This arrangement is not just predicated on the amount of the household income, but more importantly on the juxtaposed indices of poverty which include nutritional status, adequacy of the home environment, water and sanitation, environmental exposure to toxic substances, limitations of knowledge about health-seeking behaviour, and the direct effect of low social status on physiological stress and psychosocial wellbeing. [4]

Payment for health services were largely from personal resources, which has been reported in other parts of the country and associated with disparate differences in ability to cope among different socioeconomic strata. [22-24] The wide range of expenditures reported in this study indicates the high proportion of household income that is spent accessing health services. Past research has demonstrated how in lower income households, this can constitute catastrophic health expenditure. [25-27] However, the actual proportion of household income that medical or hospital expenditure constituted was not examined in this study. Though not statistically significant, there were a greater proportion of respondents with lower monthly household incomes who reported treating themselves at home before seeking treatment at a health facility. The study documented the proportion of respondents for whom reasons for self-medication before going to hospital were perceptions that the illness was not serious or that self-medication was cheaper. This practice has been well documented among different groups of patients for similar reasons of illnesses not being serious and cheaper over-the-counter drugs. [28-30] Use of complementary/alternative medications has been documented in urban settings often without the knowledge of orthodox health practitioners and this study documented that half the respondents admitted using native medication. This practice has implications for health outcomes, indicating the poor understanding of community residents for the potential for drug-herb interactions with patients. [31,32]

Implementation of national health insurance schemes have been documented to result in massive reductions in OOP. [33] Research has also documented that uptake of health services earlier in the disease process ensures better outcomes. [15,34] Factors that have been shown to influence the probability of having insurance are higher income and education levels, being married, employed, and support from the head of the household. [19,35-37]

People living in the lower socioeconomic classes and the less educated are much less likely to buy their own health insurance, with negative impact on the eventual health outcomes and cost to society. [38,39] Programmes encouraging the voluntary purchase of health insurance need to be carefully structured to avoid widening the coverage gap between disadvantaged groups in communities. [39,40] This study suggests that there are novel opportunities to encourage the uptake of health insurance for young adults and those in low- and middle-income households. [41-44] Though by no means a complete solution, replacing user fees and OOP with more sustainable and equitable financing methods will be an effective first step towards improving access to healthcare services and achieving the millennium development goals for health. [45,46]

Study limitations

This study is limited by the discordance between the estimated monthly household incomes and asset ownership which can be linked to the community residents expressed deep-seated loss of faith in the government statements; viewing the exercise as a way of imposing another levy/tax on the citizens. The ability to categorize respondents into income groups is therefore uncertain with regard to linking respondents to their reported expenditures on health services.

Furthermore, this study did not initially set out to assess the details of insurance coverage of the respondents, where or when the respondents were exposed to advertising of health insurance.

Further research is needed to relate decisions to use different mechanisms of payment for health service with availability of health insurance whether public or private.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Despite the length of time that NHIS has been in existence, awareness of health insurance was insufficient. Majority of respondents enrolled in health insurance schemes were likely enrolled by virtue of their employment rather than knowledge of the scheme. Patterns of health service utilization were associated with fever, headaches, joint and back pains. Those in lower income brackets engaged more in home treatment before going to health facilities. Hospital costs were mostly met by OOP. The authors recommend that authorities take the opportunity of encouraging the uptake of health insurance for young adults and those in low- and middle-income households using new emerging pooled funds schemes.

Future research needs to examine the proportion of household income that is spent on medical and health care. Other research needs to look into the emerging pooled funds schemes and their referral links to service delivery points.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the staff of all the primary health clinics in Mushin local government area for their kind assistance during data collection.

Author’s Contribution

BCA and AAR – participated in the design, analysis and interpretation of the study

AAR – drafted the manuscript for relevant intellectual content

AAR, BCA and AAO – participated in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Conflict of Interest

BCA and AAR – participated in the design, analysis and interpretation of the study

AAR – drafted the manuscript for relevant intellectual content

AAR, BCA and AAO – participated in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

REFERENCES

- Bhojani U, Thriveni BS, Devadasan R, Munegowda CM, Devadasan N, Kolsteren P, et al. Out-of-pocket healthcare payments on chronic conditions impoverish urban poor in Bangalore, India. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 990.

- Ezenekwe UR. Implications of households catastrophic out of pocket (Oop) healthcare spending in Nigeria. J Res Econ Int Finance JREIF Vol 2012; 1.

- World health statistics 2013. Italy: World Health Organization, 2013.

- Sachs JD. Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings. The Lancet 2012; 380: 944-947.

- Odeyemi IA, Nixon J. Assessing equity in health care through the national health insurance schemes of Nigeria and Ghana: A review-based comparative analysis. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12: 9.

- McIntyre D, Garshong B, Mtei G, Meheus F, Thiede M, Akazili J, et al. Beyond fragmentation and towards universal coverage: insights from Ghana, South Africa and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ 2008; 86: 871-876.

- WHO | Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage. WHO.

- Onwujekwe O, Hanson K, Ichoku H, Uzochukwu B. Financing incidence analysis of household out-of-pocket spending for healthcare: getting more health for money in Nigeria? Int J Health Plann Manage 2014; 29: e174-185.

- Onwujekwe O, Chima R, Okonkwo P. Economic burden of malaria illness on households versus that of all other illness episodes: a study in five malaria holo-endemic Nigerian communities. Health Policy Amst Neth 2000; 54: 143-159.

- Olugbenga-Bello AI, Adebimpe WO. Knowledge and attitude of civil servants in Osun state, Southwestern Nigeria towards the national health insurance. Niger J Clin Pract 2010; 13: 421-426.

- Charan J, Biswas T. How to Calculate Sample Size for Different Study Designs in Medical Research? Indian J Psychol Med 2013; 35: 121-126.

- Prinja S, Aggarwal AK, Kumar R, Kanavos P. User charges in health care: evidence of effect on service utilization & equity from north India. Indian J Med Res 2012; 136: 868-876.

- Onwujekwe O, Hanson K, Uzochukwu B, Ichoku H, Ike E, Onwughalu B. Are malaria treatment expenditures catastrophic to different socio-economic and geographic groups and how do they cope with payment? A study in southeast Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health TM IH 2010; 15: 18-25.

- Liu TC, Chen CS. An analysis of private health insurance purchasing decisions with national health insurance in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med 1982 2002; 55: 755-774.

- Fakunle B, Okunlola MA, Fajola A, Ottih U, Ilesanmi AO. Community health insurance as a catalyst for uptake of family planning and reproductive health services: The Obio Cottage Hospital experience. J Obstet Gynaecol J Inst Obstet Gynaecol 2014; 34: 501-503.

- Atinga R, Baku A, Adongo P. Drivers of prenatal care quality and uptake of supervised delivery services in ghana. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014; 4: S264-271.

- Hatt LE, Makinen M, Madhavan S, Conlon CM. Effects of user fee exemptions on the provision and use of maternal health services: a review of literature. J Health Popul Nutr 2013; 31: 67-80.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79: 373-374.

- Ibiwoye A, Adeleke IA. Does national health insurance promote access to quality health care? Evidence from Nigeria. Geneva Pap Risk Insur - Issues Pract 2008; 33: 219-233.

- Ustrup M, Ngwira B, Stockman LJ, Deming M, Nyasulu P, Bowie C, et al. Potential barriers to healthcare in Malawi for under-five children with cough and fever: a national household survey. J Health Popul Nutr 2014; 32: 68-78.

- Gilson L. Removing user fees for primary care in Africa: The need for careful action. BMJ 2005; 331: 762-765.

- Onwujekwe OE, Uzochukwu BSC, Obikeze EN, Okoronkwo I, Ochonma OG, Onoka CA, et al. Investigating determinants of out-of-pocket spending and strategies for coping with payments for healthcare in southeast Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10: 67.

- Ewelukwa O, Onoka C, Onwujekwe O. Viewing health expenditures, payment and coping mechanisms with an equity lens in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 87.

- Ezeoke OP, Onwujekwe OE, Uzochukwu BS. Towards universal coverage: Examining costs of illness, payment, and coping strategies to different population groups in southeast Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012; 86: 52-57.

- Makinen M, Waters H, Rauch M, Almagambetova N, Bitran R, Gilson L, et al. Inequalities in health care use and expenditures: empirical data from eight developing countries and countries in transition. Bull World Health Organ 2000; 78: 55-65.

- Onwujekwe O, Hanson K, Uzochukwu B. Examining Inequities in Incidence of Catastrophic Health Expenditures on Different Healthcare Services and Health Facilities in Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2012; 7.

- Kusi A, Hansen KS, Asante FA, Enemark U. Does the National Health Insurance Scheme provide financial protection to households in Ghana? BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 331.

- Shaghaghi A, Asadi M, Allahverdipour H. Predictors of self-medication behavior: A systematic review. Iran J Public Health 2014; 43: 136-146.

- Azami-Aghdash S, Mohseni M, Etemadi M, Royani S, Moosavi A, Nakhaee M. Prevalence and cause of self-medication in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis article. Iran J Public Health 2015; 44: 1580-1593.

- Chipwaza B, Mugasa JP, Mayumana I, Amuri M, Makungu C, Gwakisa PS. Self-medication with anti-malarials is a common practice in rural communities of Kilosa district in Tanzania despite the reported decline of malaria. Malar J 2014; 13: 252.

- Mothupi MC. Use of herbal medicine during pregnancy among women with access to public healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014; 14: 432.

- Lagunju IA. Complementary and alternative medicines use in children with epilepsy in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 2013; 42: 15-23.

- Chu TB, Liu TC, Chen CS, Tsai YW, Chiu WT. Household out-of-pocket medical expenditures and National Health Insurance in Taiwan: income and regional inequality. BMC Health Serv Res 2005; 5: 60.

- Enuameh YAK, Okawa S, Asante KP, Kikuchi K, Mahama E, Ansah E, et al. Factors influencing health facility delivery in predominantly rural communities across the three ecological zones in Ghana: A cross-sectional study. PloS One 2016; 11: e0152235.

- Beogo I, Liu CY, Chou YJ, Chen CY, Huang N. Health-care-seeking patterns in the emerging private sector in Burkina Faso: A population-based study of urban adult residents in Ouagadougou. PLoS ONE 2014; 9.

- Beogo I, Huang N, Drabo MK, Yé Y. Malaria related care-seeking-behaviour and expenditures in urban settings: A household survey in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Acta Trop 2016; 160: 78-85.

- Beogo I, Huang N, Gagnon MP, Amendah DD. Out-of-pocket expenditure and its determinants in the context of private healthcare sector expansion in sub-Saharan Africa urban cities: evidence from household survey in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. BMC Res Notes 2016; 9: 34.

- Amu H, Dickson KS. Health insurance subscription among women in reproductive age in Ghana: do socio-demographics matter? Health Econ Rev 2015; 6: 24.

- Comfort AB, Peterson LA, Hatt LE. Effect of health insurance on the use and provision of maternal health services and maternal and neonatal health outcomes: A systematic review. J Health Popul Nutr 2013; 31: 81-105.

- Spaan E, Mathijssen J, Tromp N, McBain F, Ten Have A, Baltussen R. The impact of health insurance in Africa and Asia: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2012; 90: 685-692.

- Wen H, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Effect of medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and access to care among low-income adults with behavioral health conditions. Health Serv Res 2015; 50: 1787-1809.

- Joshi A, Mohan K, Grin G, Perin DMP. Burden of healthcare utilization and out-of-pocket costs among individuals with NCDs in an Indian setting. J Community Health 2013; 38: 320-327.

- Pati S, Agrawal S, Swain S, Lee JT, Vellakkal S, Hussain MA, et al. Non communicable disease multimorbidity and associated health care utilization and expenditures in India: cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 451.

- Gany F, Bari S, Gill P, Loeb R, Leng J. Step on it! Impact of a workplace New York City taxi driver health intervention to increase necessary health care access. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 786-792.

- Chukwu E, Garg L, Eze G. Mobile Health Insurance System and Associated Costs: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Primary Health Centers in Abuja, Nigeria. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2016; 4: e37.

- Manzambi Kuwekita J, Gosset C, Guillaume M, Balula Semutsari MP, Tshiama Kabongo E, Bruyere O, et al. Combining microcredit, microinsurance, and the provision of health care can improve access to quality care in urban areas of Africa: Results of an experiment in the Bandalungwa health zone in Kinshasa, the Congo. Médecine Santé Trop 2015; 25: 381-385.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.